- MAIN INDEX: Adolf Hitler Death and Survival: Legend, Myth and Reality

- The Final Years of WWII

- "Operation Paperclip" and Underground Bases

- How the Nazis planned a Fourth Reich...in the EU

- The Great Patents Heist in Germany after WWII

- Did Hitler Have Only One Testicle?

- Argentina

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 1

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 2

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 3

- The "Race" to the Moon"

- Wunderwaffen

- Hans Kammler

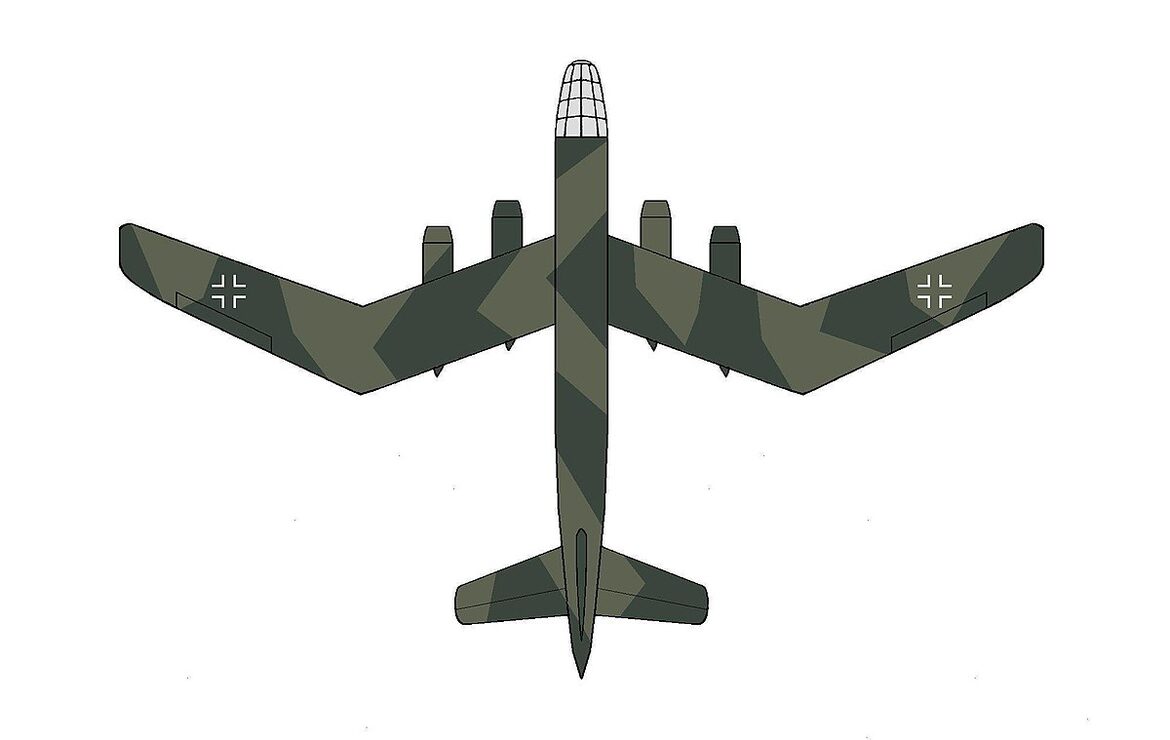

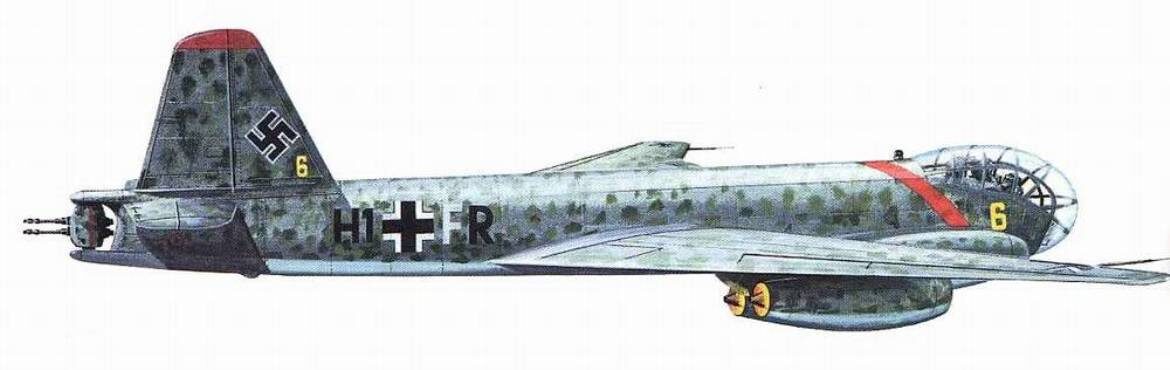

- Junkers Ju 390

- Mysterious German Bombs Aircrafts, and Carriers

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 1

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 2

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 3

- Die Glocke

- "Sweats"

- Hitler's Vergeltungswaffen

- The Coming of the 4th Reich

- “We can still lose this war” - General George Patton

- German "Super Science"

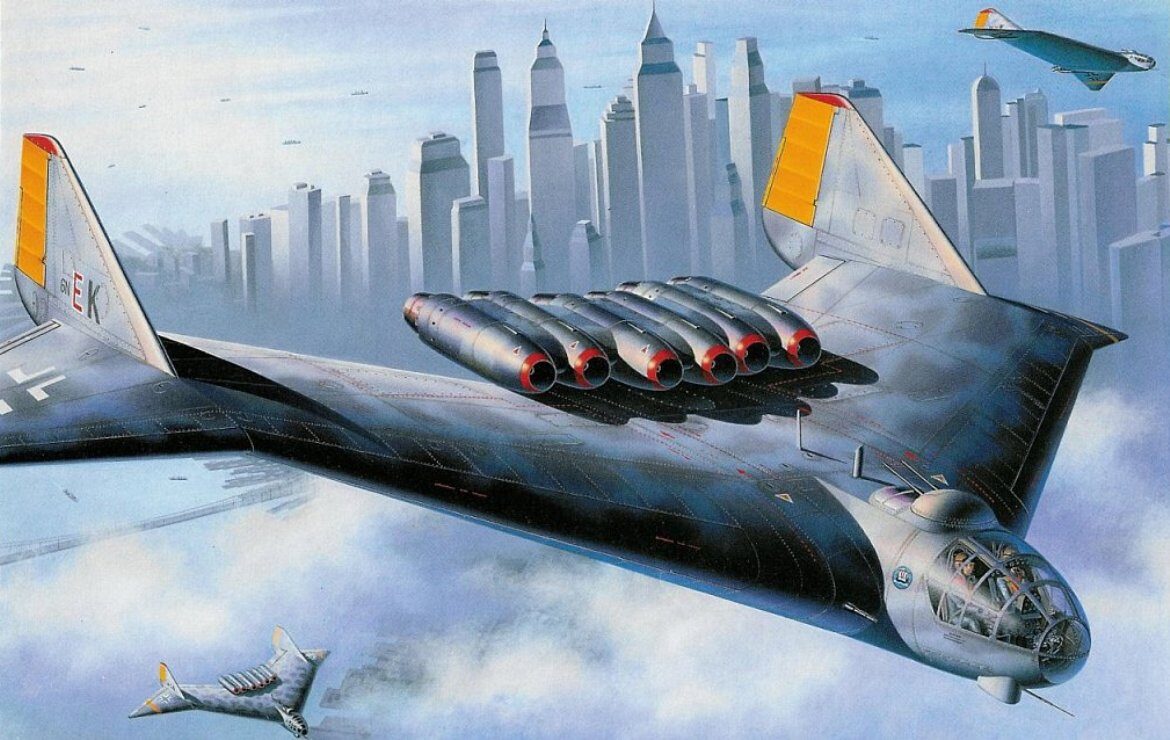

- Amerika Bombers

Amerika Bombers

Germany tried to develop airplanes capable of bombing the United States, but they could not go the distance

By Stephan Wilkinson

Aviation History Magazine

26 October 2017

Before World War II, Adolf Hitler and his advisers built a tactical air force— dive bombers, ground-attack mud movers, medium bombers for short range missions, air-superiority fighters and bomber destroyers.

For a long time there were no strategic four-engine, long-range bombers in the Luftwaffe arsenal other than the Focke-Wulf Fw-200C Condor, which was basically an airliner quickly converted for maritime patrol but not particularly suited to it.

The Luftwaffe initially used the Fw 200 to support the Kriegsmarine, for maritime patrols and reconnaissance, searching for Allied convoys and warships that could be reported for targeting by U-Boats.

It could also carry a 900-kilogram [2,000 lb] bomb load or naval mines to use against shipping, and it was claimed that from June 1940 to February 1941, Fw 200s sank 331,122 tonnes [365,000 tons] of shipping despite a rather crude bombsight.

The attacks were carried out at extremely low altitude in order to "bracket" the target ship with three bombs; this almost guaranteed a hit.

Winston Churchill called the Fw 200 the "Scourge of the Atlantic" during the Battle of the Atlantic due to its contribution to the heavy Allied shipping losses.

From mid-1941, Condor crews were instructed to stop attacking shipping and avoid all combat in order to preserve numbers.

The Fw 200 was also used as a transport aircraft, notably flying supplies into Stalingrad in 1942. After late-1943, the Fw 200 came to be used solely for transport.

For reconnaissance, it was replaced by the Junkers Ju 290, and as France was liberated, maritime reconnaissance by the Luftwaffe became impossible with the Atlantic coast bases captured.

The need for a long range aircraft must have pleased Focke-Wulf.

The Fw 200 Condor had given them a leg up in a market its rivals did not have access to. Focke-Wulf intended to keep that advantage, and would propose many long range bombers and long range naval bomber aircraft.

Focke-Wulf started a steady stream of project proposals that would eventually lead to the Ta 400.

They were all tightly focused on a low drag configuration of four to six engines that looked very similar to the Boeing B-29, but with a split tail.

The first of these Focke-Wulf called the Fw 238.

The most unusual thing about it is that it tried to use non-strategic war materials, wood and steel, for its construction.

The fuselage would have to been made out of wood, with structural hard points using steel.

It used BMW 803 radials for propulsion - another entry in the big book of linked together aircraft engines.

In this case, two BMW 801 radials were linked together and liquid cooled to create an engine with a theoretical output of 3,800 hp.

In this application, Focke-Wulf detuned them to a more sedate 2,200 hp. The engines drove a pair of contra-rotating propellers.

The crew of six wasl located in a pressurized cockpit, operating remote defensive turrets.

The Fw 238 was somewhat smaller than some proposed Amerika bombers - it had a wingspan of 50 m [164 ft] and a length of 30 m [97 ft].

That makes it closer to the B-29 in size, rather than the B-36. It had a range of anywhere from 8-10,000 km, depending on engine, and could carry the requisite 5 metric ton bomb load.

At least initially, Germany figured it would romp through Europe, invade England and win the war without ever having to deal with the United States.

In 1940, however, Hitler realized he needed a heavy bomber that could reach New York, now that a U.S. presence in the war seemed increasingly likely.

Unlike in the RAF and USAAF, the concept of the heavy bomber found few advocates within the Luftwaffe.

The lack of a strategic bomber force was a major contributor to why Germany lost the Second World War as had they been able to effectively hit the Atlantic convoys bringing much-need supplies to Britain and the Soviet production centres east of the Ural Mountains, the conflict may have turned out differently.

The RLM issue a tender for an aircraft that had a 6,000 km range, with a reserve of 1,500 km, capable of carrying 3-5 metric tons of bombs.

This was the range needed to fly from France to New York City and back again. The tender emphasized "rapid development".

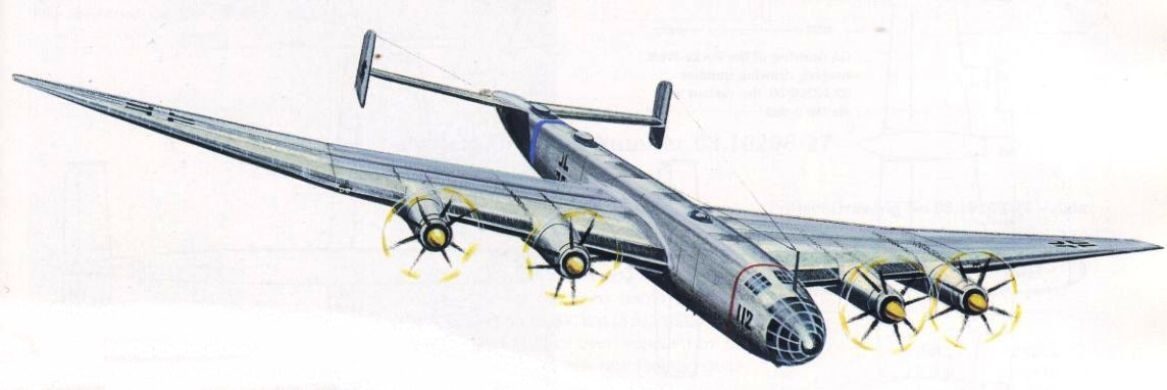

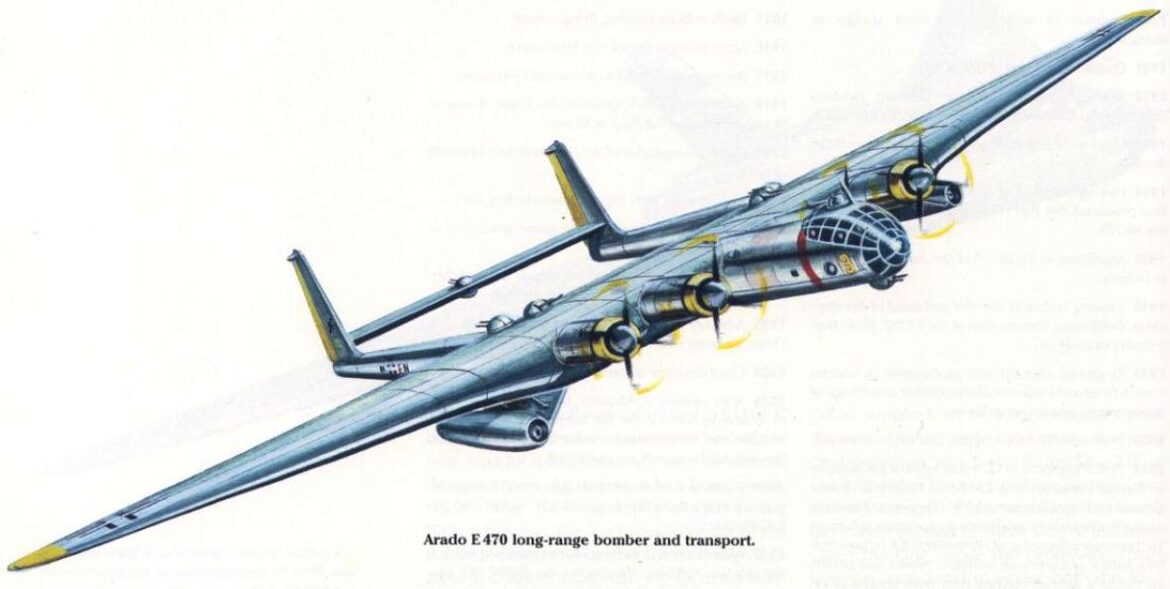

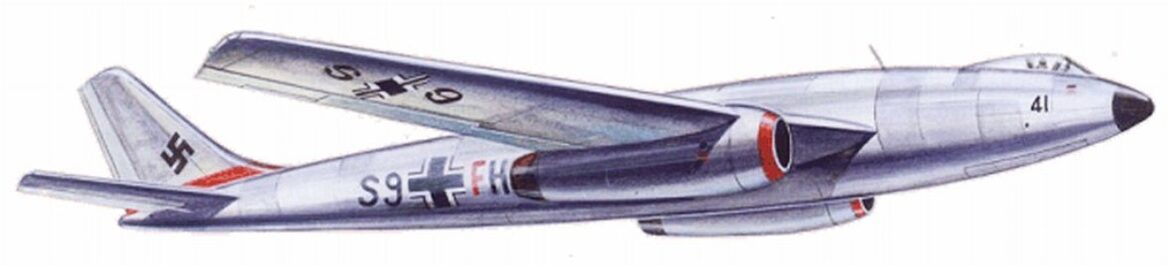

Arado, one of the German Aeronautical industry's smaller players, responded to this with the Ar E470.

The E470 was both huge and unorthodox:

It was a flying wing design, with a wingspan of 68.5 m [224 ft] and a split boom tail, like the P-38 Lightning.

The cockpit was pressurized [Arado had already built a aircraft with pressurization, the Ar 240].

The aircraft was projected to have a maximum take-off weight of 130 metric tons, twice that of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

The bomb load was 5 metric tons [11,200 lbs] with a range of 7,400 kilometers.

The E470 also had the option for four or six engines, depending on what was available. The desired engines were DB 613-9s making 3,500 hp each.

The E470 came with several model variants, with an emphasis on ultra-long range bombing or shorter range naval reconnaissance/attack.

There was also the option to turn any of these aircraft into a transport by bolting on a 30 ton external cargo pod.

The E470 had tricycle landing gear, and Arado engineers pictured a removable shipping container being attached beneath the bomb bay.

Aradoo specified a crew of four, with the navigator/radio operator/engineer manning a series of defensive turrets remotely.

The RLM declined the project in the end of 1941,

Willi Messerschmitt, for his part, had already been tinkering with such a design well before America entered the war in December 1941, despite the fact he’d been ordered to ignore everything but fighter design and production.

At a time when B-17s were already in service and the final wiring was being strung through Boeing’s first B-29 prototype, the so-called “Amerika Bomber” was still only a proposal on paper.

The original proposal stipulated a bomber that could reach New York from Portugal’s Azores, which cut about 800 miles from the round trip, making it a 6,400-mile mission.

Portugal was ostensibly neutral, but early in the war Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar had been friendly with the Germans.

That changed in 1943 when Portugal leased a base in the Azores to the Allies.

Focke-Wulf, Heinkel, Horten, Junkers and Messerschmitt were asked to respond to the request for proposals.

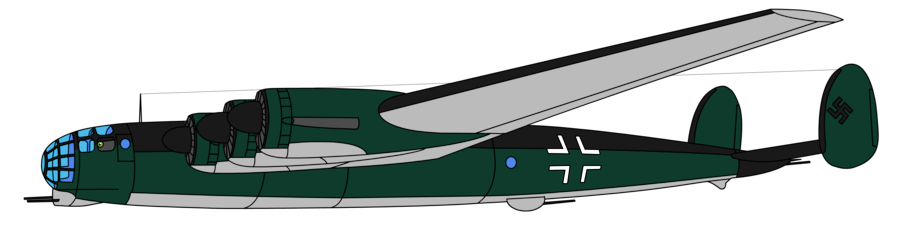

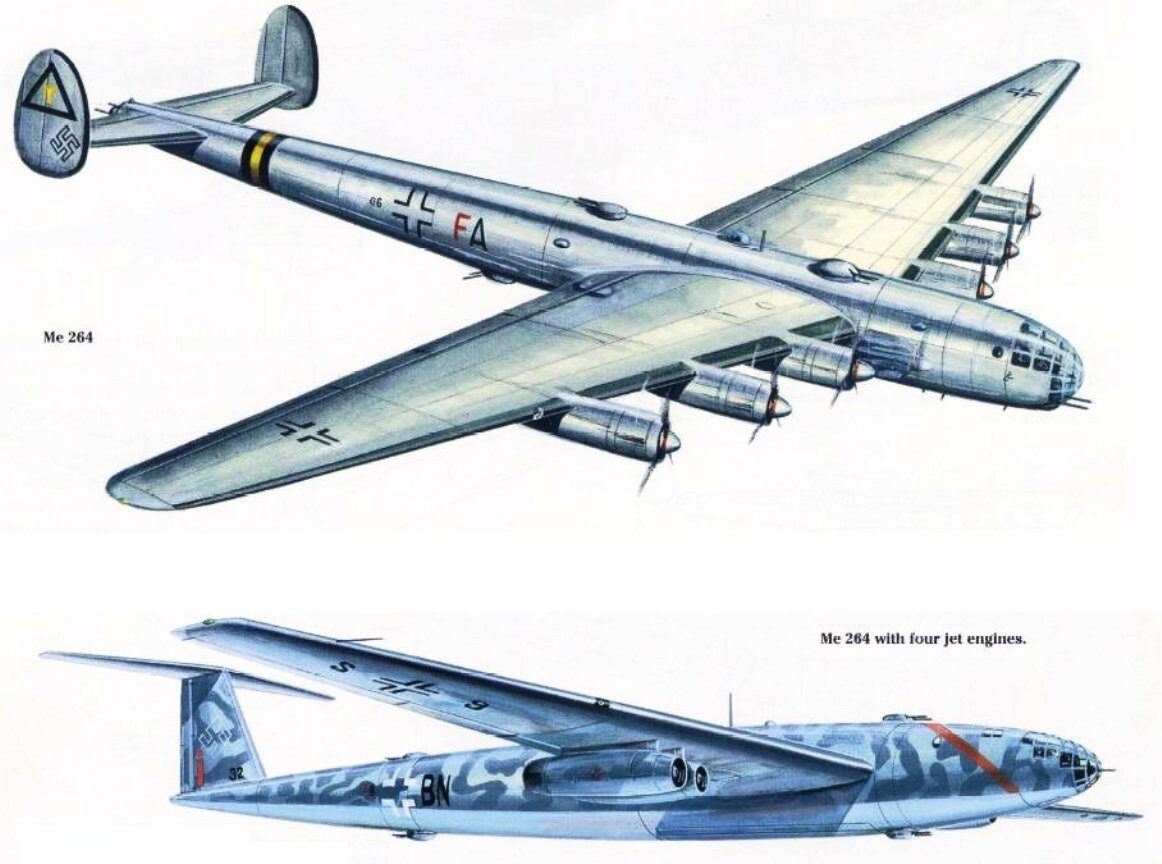

The origin of the Me 264 design came from Messerschmitt's long-range reconnaissance aircraft project, the P.1061, of the late 1930s.

In early 1941, six P.1061 prototypes were ordered from Messerschmitt, under the designation Me 264. This was later reduced to three prototypes.

The progress of these projects was initially slow, but after Germany had declared war on the United States, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium [RLM] started a more serious programme in the spring of 1942 for a very long range bomber, with the result that a larger, six-engine aircraft with a greater bomb load was called for.

To meet this demand, proposals were put forward for the Junkers Ju 390, Focke-Wulf Ta 400, a redesign of the unfinalized and unbuilt Heinkel He 277 design to give the Heinkel firm an entry in the Amerika Bomber program later in 1943.

A design study for the Messerschmitt Me 264B [unofficialy the Me 364] a heavy-duty long-range six-engined bomber with a more elongated fuselage and larger wings, was carried out.

Several schemes were proposed by the Messerschmitt design bureau to extend the range of the Me 264, including in-flight refueling, adding two more engines bringing the total to six and using take-off rocket pods for overload take-off conditions.

As the Junkers Ju 390 could use components already in use for the Ju 290 this design was chosen.

The Me 264 was not abandoned however as the Kriegsmarine separately demanded a long-range maritime patrol and attack aircraft to replace the converted Fw 200 Condor in this role.

An armed long distance reconnaissance version [Me 264A] was planned.

According to a study dated 27 Apri 1942, this aircraft should be able to fly reconnaissance missions as far as Baku, Grosnyj, Magnitogorsk, Swerdlowsk, Tiffis or Tshejabinsk in the USSR, and flights to Dakar, Bathurst, Lagos, Aden and southern Iran.

Not only were New Jersey and New York in the U.S. within range, but also targets in Ohio, Pennsylvania and even Indiana; in addition, there were plans to station some Me 264s on Japanese bases on islands north-east of the Philippines, to fly reconnaissance missions as far as Australia, India and much of the Pacific area.

This was reinforced by an opinion given by Generalmajor Eccard Freiherr von Gablenz of the Wehrmacht Heer in May 1942; he had been recruited by Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch to give his opinion on the suitability of the Me 264 for the Amerika Bomber mission.

As a result, the two pending prototypes were ordered to be completed as development prototypes for the Me 264A ultra long-range reconnaissance aircraft.

The first prototype, the Me 264 V1, was flown on 23 December 1942.

This first prototype was not fitted with weapons or armour, but of the following two prototypes, the Me 264 V2 had armour for the engines, crew and gun positions, although it was decided to complete the Me 264 V2 without defensive armament and vital equipment and the Me 264 V3 was to be armed and have the same mentioned armoured parts.

On 8 July 1943, at a meeting in the Supreme Headquarters, Hitler promised his support for the continued production of the Me 264 to Messerschmitt, but only for maritime uses.

At the same time he dropped his decision to bomb the east coast of the U.S. because "the few aircraft that could get through would only provoke the populace to resistance".

In 1943, the Kriegsmarine withdrew their interest in the Me 264 in favour of the existing Ju 290 and the planned Ju 390.

The Luftwaffe preferred the unbuilt Ta 400 and the Heinkel He 277 as Amerika-Bomber candidates in May 1943.

Based this on their own performance estimates, any further development work on the Messerschmitt bomber design was stopped.

As a consequence, in October 1943, Erhard Milch ordered the cancellation of further Me 264 development to concentrate on the development and production of the Me 262 jet fighter-bomber.

Production orders for the Focke-Wulf Ta 400 were canceled, because the Focke-Wulf resources were needed for Fw 190D-9 and Ta 152 production.

The He 277 was cancelled in April 1944.

Late in 1943, the second prototype, Me 264 V2, was destroyed in a bombing attack.

On 18 July 1944, the first prototype, was damaged during an Allied bombing raid and was not repaired, and the third prototype, not yet fully completed, was destroyed during the same raid.

Even after the cancellation order was received, work continued by many Messerschmitt engineers and designers:

In December 1944, a courier version of the Me 264, with a range of 12,000 km [7.457 miles] and a load of 4,000 kg [8,818 lbs].

Junkers, Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf came up with conventional bomber designs, while Horten suggested a six-jet flying wing.

Aero engineer Eugen Sänger, out of left field, proposed a suborbital quasi-lifting body rocket ship.

It would skip along the top of the troposphere at 13,725 mph and drop a single 8,000-pound bomb, perhaps even atomic, on Manhattan.

Junkers’ Ju-390 and Focke-Wulf’s Ta-400 proposal were uprated versions of existing designs; Messerschmitt’s Me-264, thanks to Willi’s head start, was a clean-sheet-of-paper offering that looked as though he had been given a copy of the B-29’s blueprints.

The Me-264 was a mailing-tube-fuselage, four-engine, tricycle-gear heavyweight with a hemispherical, multi-paned glass nose much like the Superfort’s.

The Amerika Bomber proposal was initially somewhat casual, with a number of implicit assumptions—the Azores as a base for one, and a high enough combat ceiling to put the bomber above the reach of U.S. interception for another, so no defensive armament or armor would be needed; drop the bombs from way up in the blue and motor on home.

By 1942, it was clear this Hund wouldn’t hunt, so the Reich Air Ministry upgraded the range, gross weight and guns-on-board criteria to the point where it became obvious that six engines rather than four would be needed.

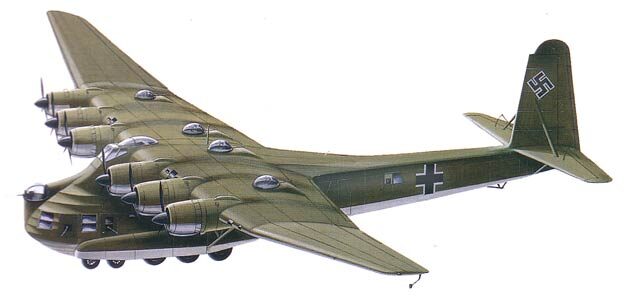

Messerschmitt in fact planned to build a six-engine Me-264B but never did, so the Ju-390 remains the largest conventional landplane ever built in Germany.

The six-engine, fabric-covered motorized glider, the Messerschmitt Me-323 had a greater wing-span and length.

The six-engine, fabric-covered motorized glider, the Messerschmitt Me-323 had a greater wing-span and length.

But it was hardly “conventional”.

The Germans never intended to bomb New York City into oblivion.

This was a mission far beyond the capability of even an Armada of slow bombers at the limit of their range, on their own without fighter escort.

The Amerika Bomber was intended as a PR weapon - as Jimmy Doolittle’s Tokyo Raider B-25s had been.

Even if the bombs did little damage, the threat of long-range bomber raids would force the U.S. to expend effort on anti-aircraft defense:

Guns and interceptors, that otherwise would have gone to war zones.

IOft course, if Germany’s attempt at developing an atomic bomb had been succeedful, the picture would have changed drastically.

One of the offshoots of the "Amerika Bomber" was the tale of the Ju-390 alleged proving flight in January 1944

It took the six-engine bomber from a Luftwaffe base near Bordeaux, France, to within less than 13 miles of New York, where the crew is said to have taken photos of Long Island before doing a 180 and heading home.

The photos have never been found.

Though there is doubtful "documentation” of the flight in the form of post-war interrogations of a few boastful ex-Luftwaffe personnel, it’s hard to believe that anybody would actually have been dumb enough to send a defenseless prototype bomber to within a few miles of Republic’s P-47 factory at Farmingdale and Grumman’s Bethpage base, both on Long Island, and Chance-Vought’s F4U swarm at Stratford, Conn., just across Long Island Sound.

The Internet continues to perpetuate this Urban Legend on a variety of WWII websites, despite the fact that the Ju-390 test pilot’s captured logbook shows the six-engine Junkers was in Czechoslovakia undergoing tests at the time of the imaginary mission, and that the airplane would have had to take off at nearly twice its proven gross weight to carry the necessary fuel.

Authors Karl Kössler and Günter Ott, in their book "Die großen Dessauer: Junkers Ju 89, 90, 290, 390. Die Geschichte einer Flugzeugfamilie" examined the claimed flight, and debunked the flight north of New York.

Assuming there was only one such aircraft in existence, Kössler and Ott note it was nowhere near France at the time when the flight was supposed to have taken place.

According to Hans Pancherz' logbook, the Ju 390 V1 was brought to Prague on 26 November 1943. While there, it took part in test flights which continued until late March 1944.

They also assert that the Ju 390 V1 prototype was unlikely to have been capable of taking off with the fuel load necessary for a flight of such duration due to strength concerns over its modified structure; it would have required a takeoff weight of 65 tonnes [72 tons], while the maximum take-off weight during its trials had been 34 tonnes [38 tons].

Another explanation for this is that prototypes are never flown at maximum gross weight for their maiden flight until testing can determine the aircraft's handling characteristics.

According to Kössler and Ott, the Ju 390 V2 could not have made the US flight either, since they indicate that it was not completed before September/October 1944.

There are other unsubstantiated, and most likely untrue, accounts of extreme-range Amerika Bomber flights.

"On 27 August 1943, a German Luftwaffe long-range photo reconnaissance bomber, a Junkers Ju-390 took off from its base in Norway and flew out across the Atlantic Ocean.

"Among its four man crew was a brave and daring woman Anna Kreisling, the ‘White Wolf of the Luftwaffe’.

"A nickname she had acquired because of her frost blonde hair and icy blue eyes.

"Anna was one of the top pilots in Germany and even though she was only the co-pilot on this mission, her flying ability was crucial to its success.

"This was to be the longest photo-recon mission flown by an enemy airplane in World War II. Nine hours later, the Junkers was over Canada and swinging south at an altitude of 22,000 feet.

"In the next few hours, it would photograph the heavy industrial plants in Michigan that were vital to the United States".

- Jim Newsom, 'The Most Dangerous Photo-Recon Mission of World War II"

The second Ju-390 prototype [only two of the type were ever built] supposedly flew from Germany to Cape Town, South Africa, in ely 1944, but no hard evidence has yet turned up to confirm Junkers test pilot Hans Joachim Pancherz’s post-war claim that he made the flight.

The sole source for the story is a speculative article which appeared in the "Daily Telegraph" in 1969 titled "Lone Bomber Raid on New York Planned by Hitler".

Hans Joachim Pancherz reportedly claimed to have made the flight in question.

James P. Duffy, "Target America: Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States" [2004] has carried out extensive research into this claim, which has proved fruitless.

Authors Karl Kössler and Günther Ott make no mention of this claim either, despite having themselves interviewed Pancherz.

The German Naval Warfare Department wrote to Reichsmarschall Göring on 10 August 1940 that long range aircraft with a range of at least 6,000 km [3,728 miles] would be needed to reach the planned German Colonial Reich in central Africa.

Also, about this time the RLM issued a requirement for aircraft with a range of at least 12,000 km [7457 miles] to reach from French bases to the United States, in anticipation of the coming war with the U.S.

In his book, "The Bunker", author James P. O'Donnell mentions a flight to Japan.

O'Donnell claimed that Albert Speer, in an early 1970s telephone interview, stated that there had been a secret Ju 390 flight to Japan "late in the war".

The flight, by a Luftwaffe test pilot, had supposedly been non-stop via the polar route.

Ju-390 Chief test Pilots Hans Pancherz and Hans Werner Lerche also referred to the polar flight to Japan.

The Me-264 was said to have made a number of non-stop flights carrying VIPs between Berlin and Tokyo, a 5,700-mile trip.

The claim likely grew out of the rumor that the plane was standing by to carry Hitler to Japan if he had been unable to quash the “Revolt of the Generals” and had to flee the Claus von Stauffenberg–led plot to kill him.

A German POW captured in April 1944 was reported in a British Intelligence report of May 1944 citing a series of Me-264 flights from Petsamo, Finland to Tokyo.

- "Luftwaffe: The Allied Intelligence Files" by Chris Staerck

The distance via Bering Straits is just 4,575nm [8,474km]

Matsuwawas, a former Japanese airbase in the Kuril Islands, plumbed with geo-thermal steam to keep it snow free year round, has German 200L drums, stamped with 1943 manufacture, all over the place.

Soviet Intelligence refers to an airfield called Usiro used for communication flights with Germany.

On Sakhalin at Usiro the Japanese built a 4,000 meter long runway - unnecessary except for the Me-264 with its fully laden 2,400 meter take off roll.

The first message about the existence of an Me 264 surfaced in July 1944, when an unknown German radio station reported that Me 264 was prepared in case of victory for the rebel generals to deliver Hitler to Japan.

It could well have been, but with the end of the Me 264 program, the only prototype aircraft was transferred to "Ozermashinen G.mb.H", for wiith a steam turbine.

The turbine had to develop a power of 6,000 hp and 6,000 revolutions per minute and be set to rotate with a 5.3-meter propeller at 400-500 revolutions.

The engine was to work with coal dust and petrol [65% coal dust and 35% gasoline].

The main advantages to this engine would be constant power at all altitudes and simple maintenance.

This aircraft too fell victim to an Allied bombing raid.

Hitler’s target: New York

Between 1940 and 1942, Hitler came dangerously close to reaching the goal of attackong New York with long-range bomber,s.

A prototype of the Messerschmitt Me 264, with a range of just under 15,000 kilometers [[9,300 miles], had already flown.

Had cities on the US east coast ever actually been attackplans of the Third Reich to attack New York with long-range bombers ed, the first atomic bomb in history would probably have fallen on a German city.plans of the Third Reich .”

Beginning in the mid-1930s, Nazi officials drew up plans for monumental construction in the five “Führer Cities” of Berlin, Nuremberg, Hamburg, Munich and Linz.

On Hitler’s orders, they were to stand in direct competition with, and even outstrip, comparable landmarks in the US: A skyscraper in Hamburg to rival the Empire State building, a bridge over the Elbe like California’s Golden Gate Bridge, and a train terminal in Munich to dwarf Grand Central Station.

Attacking New York with long-range bombers someday was a done deal among the Nazi leadership even before the outbreak of World War II. German industry also knew it.

In a speech to aviation industry managers at his villa Karinhall, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, the head of the Luftwaffe, announced his wish that the industry develop an aircraft that would “fly to New York and back with a five-ton bomb payload. I would be absolutely delighted by such a bomber"., he continued, “to finally muzzle some of the arrogance coming from over there.”.

In terms of technology, the Nazis were completely in step with the times. This was the age of larger-than-life aviators, the successors of Charles Lindbergh. In the US,

Russian pilots who flew non-stop from the Soviet Union to California were being celebrated as heroes at the time.

In 1937 Hitler ordered two long-distance aircraft from aviation designer Willy Messerschmitt that were supposed to be operational by 1940; a V1 as a courier craft and a V2, the “Führer Plane.”.

Hitler intended to transport the Olympic flame personally from Berlin to Tokyo with this airplane, popularly nicknamed the “Adolfine.”

Hitler’s ally Mussolini got wind of these plans and had a rival plane built in Italy, the “Savoia.” During World War II it flew several non-stop flights between Rome and Tokyo.

When war broke out in September 1939, the plans for long-rang aircraft changed. Military use became the only priority, and the Führer Plane, the Me 261, was developed further into the Me 264 Amerikabomber.

The Me 261’s maiden flight was delayed by the outbreak of war and took place the day before Christmas, 1940.

The tender for the successor model, the Me 264, called for a “four-engine long-distance aircraft with two tons of payload for disruptive sorties to the USA".

The plane was to be built in six versions, the heaviest of which would be a bomber with a 14-ton payload and a range of 11,500 kilometers. That would have sufficed to attack New York, as the direct distance between Brest [in occupied France] and the city on the Hudson totals 5,500 kilometers.

Hitler declared war on the United States after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Why he did so is a matter that puzzles historians to this day.

A secret report by the Messerschmitt Company from December 1941 states explicitly that “the aircraft can be used for special cases even before testing is completed"”

Yet Messerschmitt, an engineer of genius and friend of the Führer, had promised too much. The Me 264 would complete some 70 test flights, but the first took place in December 1942, a year behind schedule – luckily for America and the world.

Just how seriously the Allies took the threat of the “Amerika” bombers became evident after they learned of the plans. They launched massive bombing raids on the Messerschmitt plant in Augsburg to destroy the prototypes.

After the war, the test pilot was arrested by the British and, during questioning, attested that the plane had “absolutely first class” flying qualities.

The danger to the US east coast cities and arms industries located around the Great Lakes was, it appears, very real.

Throughout the war, the Me 264 continued to figure prominently in Hitler’s plans.

During the days when Hitler still believed he could subdue the Soviet Union in a Blitzkrieg, the airplane was frequently mentioned.

German navy briefings include an entry dated 14 November 1940 that says the Führer was planning to “attack America in case of war” from the Azores, so as to force the US to build up an air defense system instead of supplying the British with Flak batteries".

Similar entries can be found in the war logs of the German army, the Wehrmacht, compiled by Percy Ernst Schramm, a major and later a Göttingen-based historian, as well as the logs of Army Adjutant Gerhard Engel.

He recorded a remark by Hitler to him on 24 March 1941, that terror attacks on US east coast cities were necessary to “teach the Jews a lesson", as American financiers were clamoring for war.

Therefore, Hitler said, he hoped for the prompt availability of long-range bombers, which meant the Me 264.

When Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka visited Hitler in April 1941, the latter told him to expect a “vigorous fight” against the Americans with submarines and planes.

In a briefing with navy brass a few weeks later on 22 May, Hitler fantasized about capturing the Canary Islands and the Azores to use “the long-range bombers” against the Americans, which would become possible that fall, he believed.

At the time Hitler was counting on a speedy victory against the Soviets. Then he could keep the Americans away from the European theater and force them into adopting a defensive strategy.

Hitler made his calculations without Churchill’s Britain and Stalin’s Soviet Union, which kept on fighting despite appalling losses.

As early as 22 May 1941, the Führer confided to his friend Walter Hewel that if the eastern campaign failed, “it’s all over anyway".

Back home, meanwhile, the war and the Third Reich’s chaotic bureaucracy helped ensure that the Me 264 would never be mass-produced.

In August 1944 the Messerschmitt works abandoned their final attempt to launch production. Yet right to the bitter end, the plane continued to soar through Hitler’s imagination.

In the Bunker of the Reich Chancellery, he ordered a rival of Speer to implement Messerschmitt’s design for a four-engine bomber.

“With the range of this plane we can avenge the destruction of our cities a thousandfold over America!” he was quoted as saying.

In July 1945 the Americans interrogated the military leadership – the former generals and admirals Hermann Göring, Karl Dönitz, Wilhelm Keitel, Alfred Jodl, Herbert Büchs and Walter Warlimont – about German plans to attack the Panama Canal and the US. The defeated officers shook their heads, saying they had never heard of such plans.

Only Warlimont, who had worked as a general in Hitler’s HQ and was the sole general staff member who knew the United States, admitted years later hat the planned terror attacks would have caused substantial fear in the US.

Just a few planes would have sufficed. And, above all, Hitler’s Germany would have gained some time.

Luckily, reality took a different turn.

Junkers Ju 390: the Ghost Plane

The following article about the long-range bomber Junkers Ju 390 comes from Friedrich Georg, the author of the two-volume work "Hitlers letzter Trumpf" [Hitler's last trump card].

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Junkers Ju 390. a piston engine powered long-haul aircraft, is still associated with an unsolved mystery.

Under the date of 9 February 1945, two flights with the Ju 390 V-2 were entered in the flight log-book of Flugkapitän Oberleutnant Lieutenant Joachim Eisermann: One of 50 minutes flight time in Rechlin itself, the other of 22 minutes from Rechlin with subsequent landing in Lärz, the aerodrome also belonging to the E-site.

An identification number is, as is unfortunately frequently so in Rechliner flight books, not registered.

According to Lieutenant Eisermann, the plane stayed in Lärz, but all traces of it disappeared, When members of the FAGr.5 spent a some time time in Rechlin and Lärz a month later, the plane was gone. No one knows until today exactly what happened to the plane. There is no a date for its destruction, nor was it captured by Allies.

But it becomes even more mysterious:

Prof. Heinrich Hertel, chief designer and technical director of the Junkers aircraft and engine works, when he was interrogated by the British on 26 September 1945, stated that the Ju 390 V-2 was neither finished, nor flown. The same was said by Flugkapitän Hans Joachim Pancherz, who would have been the project pilot for the test flight.

What secret was being hidden?

As early as 1942, Junkers participated in a competition in which the Technical Bureau had put out to tender a long-range bomber capable of striking targets in the United States, notably New York.

Heinkel took part in this competition with the He 274 and He 277, Messerschmitt with the Me 264 and Tank with the Ta 400 and the projects 0310224.30 and 0310225 .

The tender was for a long distance reconnaisance, transporter and guided missile carrier, with a range of 12,000 km .

Under the direction of Dipl. Ing. Heinz Kraft, the Junkers construction office in Prague began work on a six-engine Junkers Ju 290 C, whose fuselage and surface area were significantly increased by the construction of fuselage and surface spacers.

Since this solution required the least amount of materiel and equipment, Junkers was commissioned to build two prototype aircraft .

However, on 10 October 1942, the urgency level for the program was downgraded.

Since the Ju-90 could be used in construction, the first flight of the Ju 390 Vl with the liidentification number GH + UK took place on 21 October 1943.

Because of her good flying properties she was intended for series production.

In May 1944, considerations were made at Junkers, how the Ju 390 could be relieved iof weight, to ifurther improve her so far reached range of 8,500 km.

The reason was new specifications was, that for political reasons, the range was raised to 11,000 km with a payload of 8 tons.

These new performance demands were to be achieved for a launch weight of 80.5 tonnes with the removal of 5 tons of equipment and armament.

Furthermore, in the winter of 1944/45 Hermann Göring imposed the same requirements on the "Amerika" jet bombers, although it is an open secret today that these jet aircrafts were to transport a radiological or nuclear weapon to New York.

Thus, the reason for these "political reasons" of May 1944 must have been the planned transport of a "Victory Weapon" by the Ju 390, but the author of the post-war report did not want to or was not allowed to express this.

Earlier, in November 1943, Hitler's personal pilot, Flugkapitän Hans Baur, had already requested a Ju 390 for the Regierungsflugstaffel [F.d.F]. The aircraft was to serve as a replacement or supplement for the previously flown Focke-Wul 'Condor'.

Was the Ju 390 to be used for courier flights to friendly Japan with this aircraft at the highest level, or was it already planned as an escape aircraft?

In view of the already considerably shrunken borders of the German sphere of influence at this time, the great range of the Ju 390 would not have been necessary.

The further history of the Junkers Ju 390 is filled with ambiguity and contradictions.

Due to the excellent results of the Ju 390 V-1 flight testing, it was decided to shorten the aircraft and not to build any V and O types, but to consider the improvised Ju 390 V-1 as a prototype for the series.

A report of October 1943, however, states in March 1944, that six experimental aircraft V-2 to V-7 and twenty production aircraft should be built as A-1, with the completion of the V-2 and its testing planned for late September 1944. Six weeks later, the V-3 was to be completed, and was to have the final bomber hull of the A-1 series.

On 20 June 1944, however, the entire Ju 390 program was canceled by Hermann Göring.

In early 1945, the Ju 390 was suddenly to be built in series again.

Apparently, the RLM did not want to rely solely on the planned long-range jet bombers.

On 17 April 1945, however, it said in a telex: "The 'Junkers Lastwagen' can not be built due to jet propulsion production....".

This proves at the same time that the term Junkers truck was a stealth designation for the Ju 390.

Current research shows that the Junkers Ju 390 Typ V-1 and V-2 were completed.

Other components for other Ju 390 aircraft should have already existed. Virtually nothing is known about the V-3, the actual bomber version, and it is not sure when the V-2 was completed.

As early as October 19, 1943, trim weight trials on the Ju 390 V-2 were reported in a Dessau document by Prague.

As a further proof of its existence, replica documents of the Junkers company of 6 October 1944 clearly show components that do not belong to the Ju 390 V-1.

There is also a controversial aerial photograph, whose details differ significantly from those of the> Ju 390 V-1. This photo shows a Ju 390 with the [retouched?] identifier "RC + DA".

Clearly differing from the V-1, the front fuselage of the RC + DA is about 1.5 m longer from the wing edge to the fuselage tip, and the machine has other vertical stabilizers.

These modified parts correspond exactly to those of the replica documents of the fall of 1944.

It is likely that the Ju 390 V-2 was originally completed as a heavy bulk carrier.

Also on the photograph of the Ju 390 V-2, no armed body parts are recognizable. H

owever, it is contradictory that an armed bomber version is marked on the replica documents destined for Japan and 1944 shooting tests of a Ju 390 are reported in October 1944.

How can this be explained?

From the German side, the armament of the future Ju 390 were fiercely contested until its construction.

Much work was carried out on sample mounts and armament variations.

This went so far that the Henschel company supplied a custom built "Fernvisier [Fevi] mit Vorhalterechner" [remote visor with pre-calculator] for the Ju 390 to Prague.

Was the Ju 390 V-2 Großtransporter now converted to an armed version, or was there a V-3?

Due to the previous extensive experimentation and models, a complete V-2 fuselage conversion into a bomber version would be conceivable, but the photographic proof is missing.

One of the easiest to be realized possibilities would have been the installation of so-called "Schlüssellochlafetten mit eingeschränktem Richtbereich" [keyhole carriages with a limited traverse range].

These relatively light carriages for the installation of 3 cm MK 108 cannons were supplied for the Ju 390 and could have been installed in the existing transporter hull of the V-2 without too much conversion effort. The bomb load would be attached to ETC outdoor girders on all Ju 390 versions.

In just seven hours, the single Ju 390 was to reach the USA from Bordeaux and drop its first German bombs on New York.

As a support aircraft and escort fighter, two Ju-635 were intended to protect the plane on its lonely flight across the Atlantic.

Hitler had considered the Ju 390 to be too vulnerable to Allied air defenses otherwise.

In 1944, Junkers helped Dornier with work on the Do 335 Zwilling or Dornier Do 635. A meeting was arranged between Junkers and Heinkel engineers, and after the meeting, they began work on the project.

The designer, Professor Heinrich Hertel, planned a test flight in late 1945.

At the end of 1944, the Germans reviewed aircraft designs with the Japanese military. Among other projects, the Do 635 impressed the Japanese military with its capabilities and design.

This design consisted of two Do 335 fuselages, joined by a common centre wing section, with two Rb 50 cameras in the port fuselage for aerial photography.

Armament was confined to provision for five 60 kg [130 lb] photo-flash bombs.

It was also intended that two Walter HWK 109-500 RATOG units would be fitted.

In early 1945, a wind-tunnel model was tested, and a cockpit mockup was constructed, but the project was cancelled in February 1945, due to the desperate war situation.

The Secret Ju 390 - Long-distance Flights

Did the Ju 390 fly to Japan?

The cover of the picture of the magazine "Fliegergeschichten aus dem Jahre 1961" had the title "Flug in die WeltgeschichteF" [Flight into world history].

Was the Ju 390 V-2 perhaps finished sooner than in September/October 1944?

In that case, the disputed test flight from Mont-de-Marsan [France] to close to New York) would have been possible too.

As mentioned in English secret reports since August 1944, it should have taken place in early 1944.

British Intelligence then hesitated to pass this information on to the Americans for fear that the US would bring back their fighters from England for Homeland Security.

According to English reports, photos would have been back, showing the American coast of Long Island at a distance of 20 km.

The proof would be provided by the presentation of these photos.

The reason for such a flight can only have been a feasibility test of an attack on New York.

.

Did this flight provide the 8,500 km range coverage mentioned in the company documents , or did it happen in a Ju 390 non-stop flight to Capetown, South Africa, as Colonel Hans Pancherz reported in the post-war period?

After this successful test run one would have dared to make the actual effort.

In this context there must have been another attempt to improve the range over the Atlantic, for in the curriculum vitae of the Ju 390 "investigations are made of "Anhängeflugzeuge" with regard to the shooting of the tow-plane over the Atlantic ....." are mentioned.

Unfortunately, the exact term in the post-war documents was deliberately defaced, so we do not know what failed attempt are referred to.

What could have been the mysterious reasons that led to the "denial" of the successor to the Ju 390 V-1?

The fate of the Ju 390 V-1 is clear:

Since a military commitment of this makeshift zpieced-together aircraft was out of the question, it was further tested in Prague until it was brought by Flugkapitän Pancherz on 15 November 1944 to Dessau, where it was it remained parked without propellers,

until the end of the war

The burned-out remnants of the machine, which was still lit shortly before the the area was over-run by the Allies, were evaluated in exacting detail by the Americans.

For the ultimate fate of the Ju 390 V-2 [or V-3?], there are several theories, its destruction or capture was announced at the end of the war:

- The machine would have beeen used for a [failed?] Secret Mission.

- The machine served NS notables as an escape machine.

- The machine was delivered to allied Japan.

For the first option, the secret special order, it should be noted that the Ju 390 V-2 would have been a fully operational long-range fighter aircraft. Also, the fact that the V-2 was in October 1944 in Rerik [Baltic Sea] for testing of its of the weapon system , rather speaks for this possibility.

The long-range bomber would have been able to transport a bomb load of 4,400 kg [equivalent to the weight of the Hiroshima bomb] to New York at a maximum speed of 472 km/h and a service altitude of 8,900 m .

Was the Ju 390 V-2 to be flown from Norway to New York in March 1945, carrying a nuclear bomb?

Technically, this would have been possible.

There exist never revoked messages, that near Oslo long distancer bomber were ready to be used against the United States at the end of the war.

The intention for a never carried out atomic bomb mission would be a reason for the concealment of the existence of the Ju 390 V-2 in the post-war period.

The former Junker test pilot Pancherz then announced in the "London Daily Telegraph" on 2 September 1969 that a single Ju 390 had been built specifically for the purpose of bombing New York according to Hitler's plans in a single attack.

the planned flight was canceled due to "lack of funds". «has been canceled .

The aircraft, flown in and tested by him aircraft, was then burned at the approach of US troops.

The second possibility that the Ju 390 V-2 served as an escape plane for Nazi VIPs would also have been delicate.

One only need consider the possibility that SS Obergruppenführer Dr. Hans Kammler could have set off with the help of this long-distance aircraft from Bohemia and Moravia shortly before the end of the war.

As is known, the alleged death of Kammler is associated with many legends and contradictions.

The third, and most likely possibility is a transfer of the Ju 390 V-2 to Japan.

The Japanese army was keenly interested in the Ju 390, which could have used this plane to attack the US West Coast from Japan, and Japanese designs for such aircraft were still in the project stage.

There is a collection of replica documents, all from the fall of 1944, that prove that at that time Junkers was working with approval or even on behalf of the RLM in compiling the documentation needed to replicate the Ju 390 in Japan.

In February 1945, all documents were still finished, but allegedly they could no longer have been sent to Japan.

However, according to the Kammler researcher Tom Agoston. a Luftwaffe test pilot of the Luftwaffe on 28 March 1945, flew a a six-engined long-range bomber Ju 390 non-stop via the polar route to Japan. It can only have been the Ju 390 V-2 under the circumstances.

It was flown from Norway on a great route to Manchukuo. The flight led from the starting airfield Bardufoss in northern Norway first to the Bering Strait, then in a right turn over the North Sea east over the Kamchatka Peninsula to the island of Pamushiro - Japanese held area.

From there it went on via Manchuria to Tokyo.

During the flight near the North Polar Region astro-navigation would have been used due to the expected compass failure.

According to Agoston, on board the machine were important spare parts, microfilms and possibly also key personnel.

As well, Major General Fritz Morzik, one who would have to know it as former "General der Transportflieger", wrote in an official post-war study of the USAF that the Ju 390 was used for courier flights to Japan.

The American editor, however, hastened to add that no additional information about Ju 390 flights to Tokyo could be found.

Technically, the Ju 390 would have been capable of such an outstanding flying feat.

The necessary weather stations in the Arctic were also already available.

In addition to numerous automatic weather stations that were transported by submarines to various locations, from Labrador to Greenland, so did the "Wettertruppe Haudegen" from September 1944 out of Spitsbergen.

The station, which was particularly active from the end of the polar night in March 1945, then got a request from their headquarters in Norway, whether the Haudegen team wanted to stay on Spitsbergen, not until autumn 1945, as planned, but until autumn 1946.

In that case, two planes with supplies and reinforcements were to be sent.

But they never arrived there.

It is very interesting from the point of view of war history that the intention on the German side was obviously to continue the war from Norway .

The station Haudegen capitulated only on 4 September 1945 as one of the last known units of the German Wehrmacht.

So far, however, no confirmation of the polar flight of the Ju 390 V-2 has been found in Japanese records, just as there are no other indications of their whereabouts.

There are only publications of intercepted Japanese radio messages that have an intended Ju-290 flight to Japan in May 1945 on the subject.

Were the radio messages about the transfer of rhe Ju 390 suppressed?

In the radio report of the attaches of the Japanese naval air force in Germany from 21 March 1945, reference to an intended co-ordinated express air and sea transport to Japan appeared, which were to take place within a three-week period.

The arms and documents suitable for transport by sea then went out together with the persons destined for Japan on 25 March 1945 with U-234 and later with other submarines at sea.

Was the airlift intended for co-ordinated transport carried out by the Ju 390 V-2 on 28 March 1945?

Tom Agoston sent the author a copy of Kammler's telegram of 17 April 1945 as proof that at that time a Ju 390 was still available.

A photo allegedly shows a Ju 390 during start preparations in Prague in the middle of April 1945.

It seems interesting at this point, however, that even on 17 April 1945 apparently a sable Ju 390 was in the German sphere of influence.

SS-Obergruppenführer Dr. Kammler officially sent to his superior, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, a secret, personally signed four-line telegram message with the following text:

"Betr. LKW. Junkers. - According to a Führer Order, actions for jet planes precede military ones. - That's why I have not been able to release the desired LKW".

This can only mean that the second Ju 390 [Junkers Truck] either did something other than Agoston wrote -never flew to Japan- or was back from there alread.

A third option is that there was another Ju 390 in Kammler's command area, which was then the one dealt with in the telegram of 17 April 1945.

Was the V-3 still finished?

But General Kammler did not want the plane for himself.

According to credible reports, a Ju 390 [V-2 or V-3] on 2 May 1945 by left Bodo [Norway] with a 4 man crew and a secret cargo.

After a stop-over to refuel in Villa Cisneros [Spanish Dahara], it proceeded to Uruguay, where the blue-painted, provided with Swedish identifiers machine on 4 May 1945 landed safelly in a location not far from the Argentine border.

There it was scrapped to leave no unnecessary tracks.

Messerschmitt Me.P.08-01.

In May 1942, as the war situation worsened, the design bureaus of Focke-Wulf, Junkers and Messerschmitt all sought to develop a long-range bombers which could be able to carry 4,000 kg bomb load into U.S. air-field, where they could mount bombing raids against targets along America's eastern seaboard.

The main target for such attacks was to have been New York.

One of the designs was the Messerschmitt Me.P.08-01.

The original Me.P.08-01 project started in September 1941 as a long-range bomber, reconnaissance, tactical large-capacity transport, airborne anti-aircraft platform and tug for towing gliders.

Combined with this wide variety of roles, the proposed flying wing configuration would offer good climb and combat performance.

The fuselage and crew cabin were faired almost completely into the center-section of the wing.

But on March 1943, the RLM issued a decree forbidding all further work on heavy bomber projects.

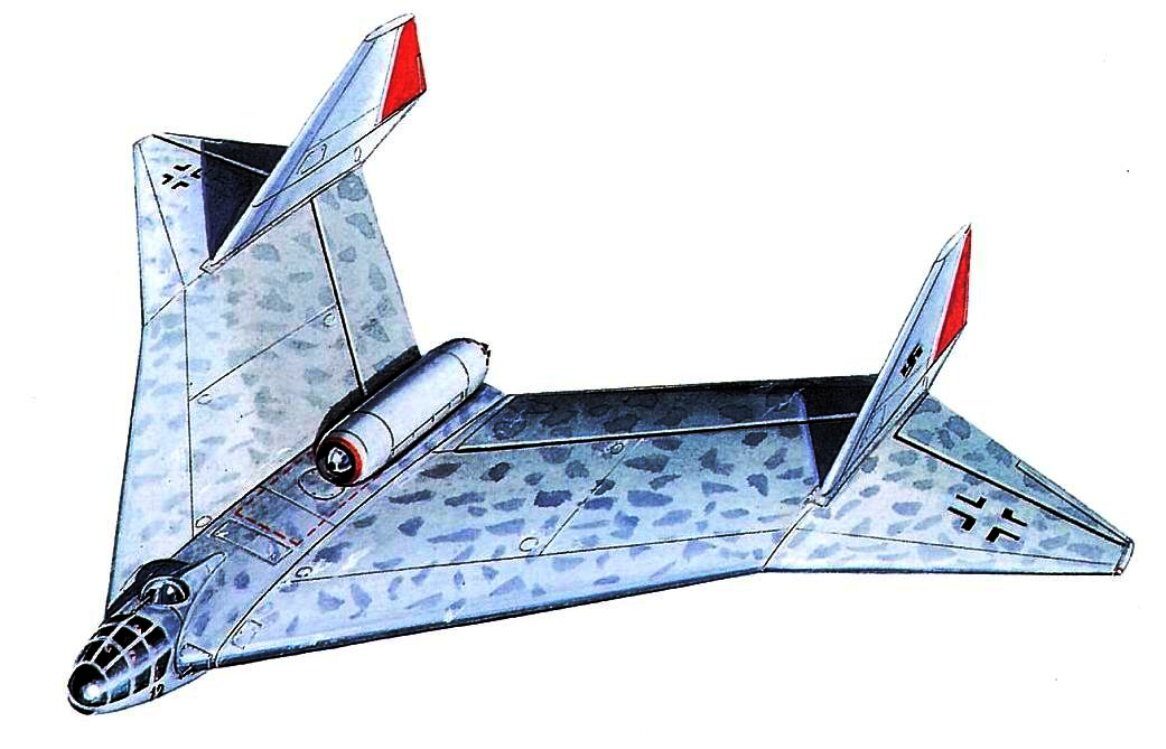

Arado Ar E.555 series

In mid-December 1943, at the Arado facilities in Landeshut/Schlesien, work began on a flying wing project series under the direction of Dr.-Ing. W. Laute.

This was further elaborated by Dipl. Ing. Kosin and Lehmann of Arado under the title of "Long Range/High Speed Flying Wing Aircraft".

A discussion took place with the RLM several months later in early 1944, and Arado was asked to compile design studies for a long range jet powered bomber.

Since the requirements were high speed, a bomb load of at least 4,000 kg [8818 lbs] and a range of 5000 km [3,107 miles], it was realized that the project could best be fulfilled by using a flying wing design with a laminar high speed profile.

The number of designs eventually reached fifteen, and included strategic bombers, remote controlled weapons carriers and fighters.

The Arado Ar E.555-1, constructed entirely of metal [both steel and Duraluminum], was basically a flying wing with a short, circular cross section forward fuselage where the pressurized cockpit was located.

There were two large vertical fins and rudders that sat 6.2 m [20' 4"] from the centerline of the aircraft.

The main landing gear undercarriage consisted of two tandem, dual wheeled units that retracted inwards into the wing, and the front landing gear was a single, dual wheeled unit that retracted to the rear to lie beneath the cockpit.

A droppable auxialiary landing gear could be used for overload conditions.

Power was to be provided by six BMW 003A, all located on the rear upper surface of the wing.

Defensive armament consisted of two MK 103 30mm cannon in the wing roots near the cockpit, a remote controlled turret armed with two MG 151/20 20mm cannon located just behind the cockpit.

A further two MG 151/20 20mm cannon were in a remote controlled tail turret, which was controlled via a periscope in a pressurized weapons station behind the cockpit area.

On 28 December1944, Arado was ordered to cease all work on the E.555 series, due to the worsening war situation, and the need to concentrate aircraft development and production on fighters.

Arado Ar E.555-3

Arado E 555-6

Arado E 555-7

Arado E 555-11

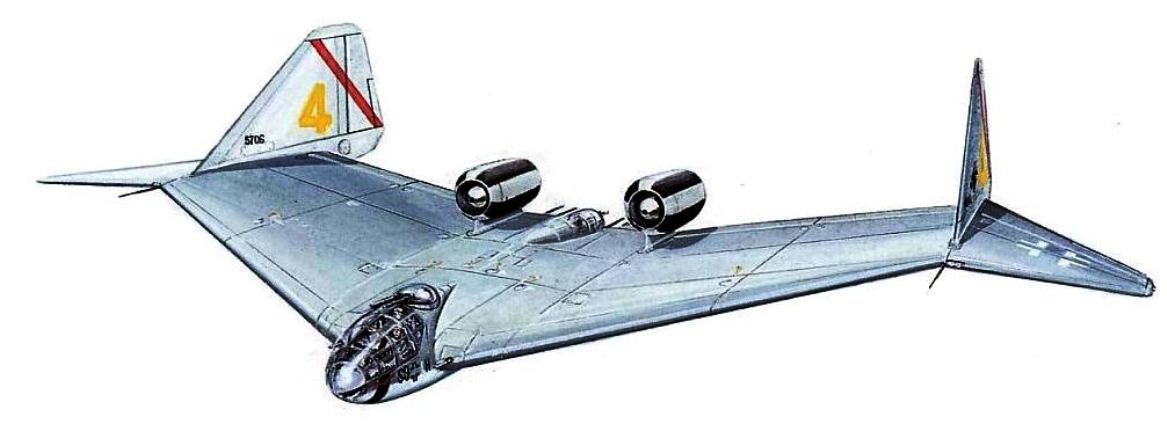

The Junkers EF.130 was designed at the same time as the Ju EF.128. This flying wing design was powered by four BMW 003 turbojets mounted side-by-side above the ventral trailing wing edge.

The construction was to be of metal, with wooden outer wing sections. A small glazed pressurized cockpit was located in the extreme nose for a two or three man crew.

Landing gear was to be of a retractable tricycle arrangement, and no defensive armament was known to have been fitted. A bomb load of 2,950 kg [6,490 lbs] was to be carried.

The Focke-Wulf 1000x1000x1000, also known as Focke-Wulf Fw 239, was a twin-jet bomber project for the Luftwaffe, designed by the Focke-Wulf aircraft manufacturing company during the last years of the Third Reich.

Their designation meant that these bombers would be able to carry a bomb that weigh 1,000 kg for a distance of 1,000 km at a speed of 1,000 km/h.

Focke-Wulf produced three different designs of the project that would have been powered by two Heinkel HeS 011 turbojet engines. The innovative-looking series of jet bombers was designed by H. von Halem and D. Küchemann.

The project was cancelled because of the surrender of Nazi Germany.

Variants

The Focke-Wulf 1000x1000x1000 project had three different variants. All of them were twin-jet bombers that would be powered by two Heinkel-Hirth He S 011 turbojets.

The Fw 1000x1000x1000 A project looked conventional; it had thin wings, swept back at 35 degrees.

The Fw 1000x1000x1000 C, with a crew of three looked quite similar to the Fw 1000x1000x1000 A.

The Fw 1000x1000x1000 B was a flying wing design with a small fuselage containing the cockpit and the front undercarriage wheel.

_____________________________________________________________________

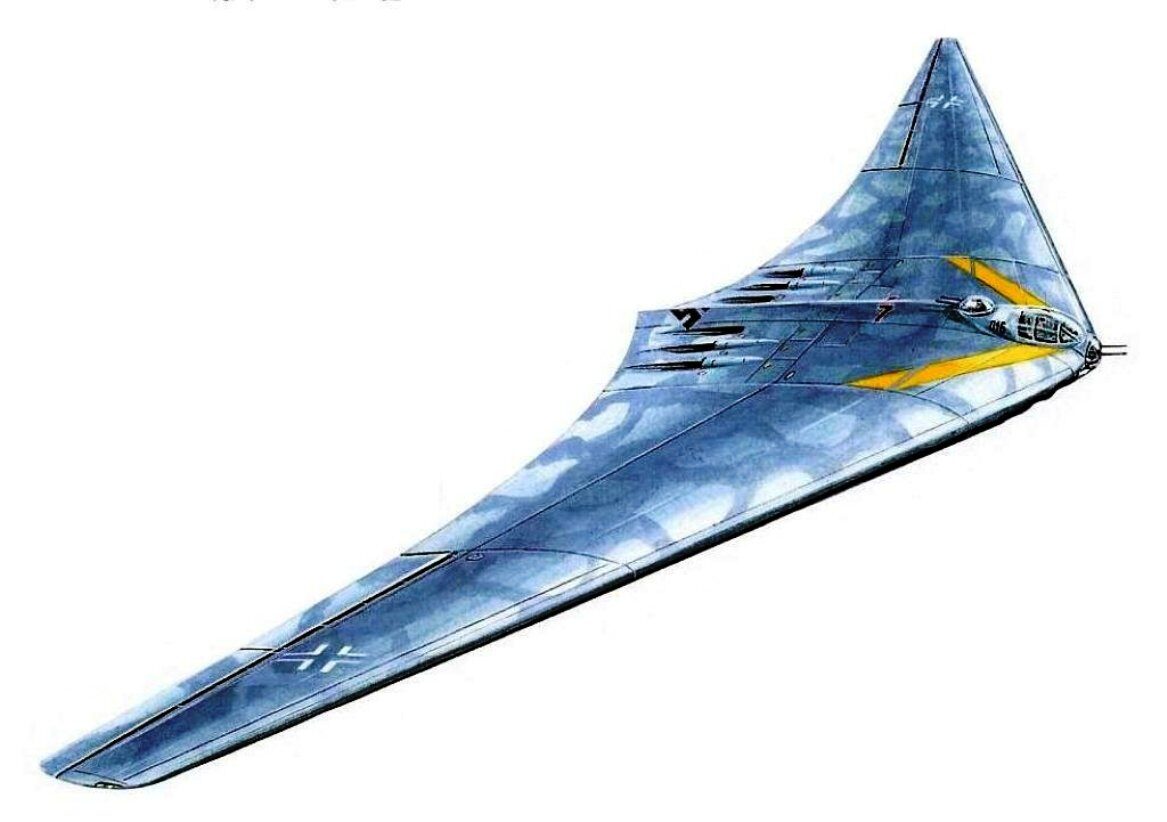

The Horten H.XVIII was a proposed German World War II inter-continental bomber, designed by the Horten brothers with pioneering features:

A flying wing configuration, turbojet engines and stealth characteristics.

The unbuilt H.XVIII represented, in many respects, a scaled-up version of the Horten Ho 229, a prototype jet fighter.

The H.XVIII was one of many proposed designs for an Amerikabomber, and would have carried sufficient fuel for transatlantic flights.

Software modelling has suggested that the stealth and speed of the Hortens' flying wing jet designs would have made interception, prior to bombing, difficult and unlikely.

For instance, it has been suggested that Ho 229 raids on England would have been undetectable by radar, until such a bomber was within eight minutes or 80 miles [129 km] of its target.

The ability of bomber crews, in an aircraft such as the Horten H.XVIII, to attack targets in North America, hower, would have been hampered by existing and emerging Allied air defence strategies and technologies.

Such as:

- Increasing air attacks on German factories and airbases

- Intelligence gathering, especially advances in cryptanalysis;

- Ongoing improvements in radar [especially early warning and airborne radar

- High-altitude and/or long-range combat air patrols.

Variants

H.XVIIIA

The A model of the H.XVIII was a long, smooth blended wing body. Its six turbojet engines were buried deep in the wing and the exhausts centered on the trailing end.

Resembling the Horten Ho 229 flying wing fighter there were many odd features that distinguished this aircraft; the jettisonable landing gear, and the wing made of wood and carbon based glue, are but two.

The aircraft was first proposed for the Amerika Bomber project and was personally reviewed by Hermann Göring:

After the review, the Horten brothers [with deep dissatisfaction] were forced to share design and construction of the aircraft with Junkers and Messerschmitt engineers, who wanted to add a single rudder fin as well as suggesting underwing pods to house the engines and landing gear.

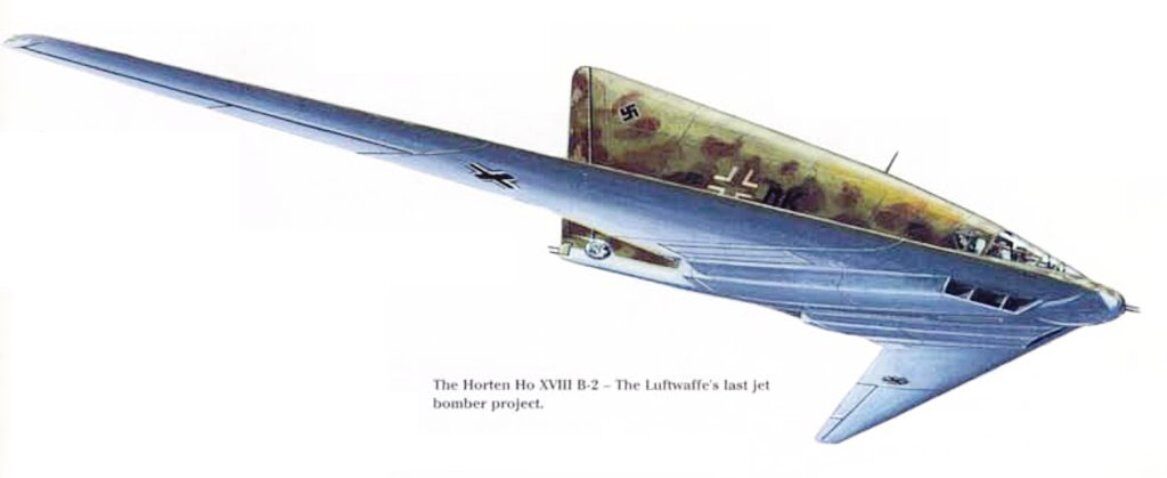

H.XVIIIB

The B model of the H.XVIIIB was generally the same as the A model, except the four [down from six] engines and four-wheel retractable landing gear were now housed in underwing pods, and the three-man crew housed under a bubble canopy.

The aircraft was to be built in huge concrete hangars and operate off long runways with construction due to start in autumn 1945, but the end of the war came with no progress made.

Armament was considered unnecessary due to the expected high performance.

H.XVIIIC/B-2

The C model of the H.XVIII was based on the airframe of the H.XVIIIA with a huge tail.

It had an MG 151 turret set in the middle rear of the wing and with six BMW 003 turbojets slung under the wings; this was designed by Messerschmitt and Junkers engineers.

It is uncertain if this overall design was directly developed by the Horten brothers or their manufacturer, as there is little surviving evidence of this proposed version. It was eventually rejected by the Horten brothers, as it was not a major improvement over the Ho XVIIIA.

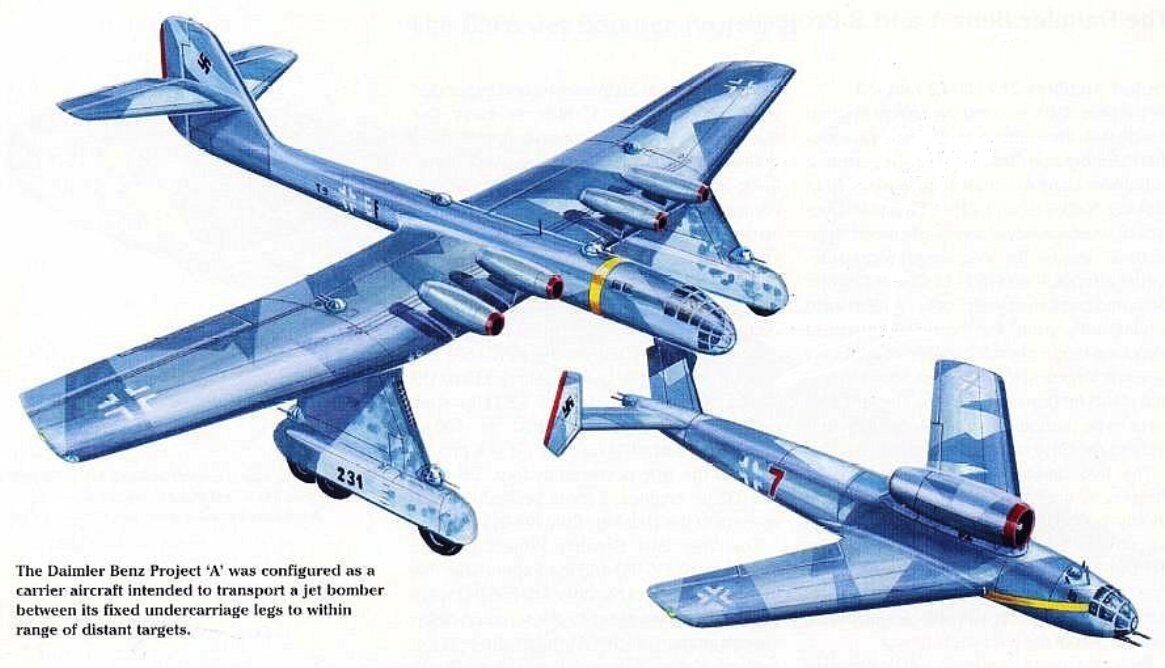

In 1943, instructed by Reichsmarschall Göring to design and produce very long-range bombers which would be capable of attacking targets in the U.S.A. and Soviet industrial plants far beyond Germany,

Daimler-Benz combined with Focke-Wulf to form a joint study group for the development of ultra long-range aircraft.

These strikes were to be carried out in non-stop flight and without recourse to aerial refuelling.

The two designs, simply referred to as Project-A and -B were to have been built in 1944.

The Project-A was a carrier aircraft designed to transport a jet bomber. This combination was to have been capable of delivering a 30,000kg bomb load over distance of 17,000km.

The project-B was an improved version of Project-A, that was not only able to carry a jet bomber, but also five manned explosive delivery systems to distant target areas.

Their destructive effect was far greater than that of conventional bombs.

The project never went beyond the drawing board.

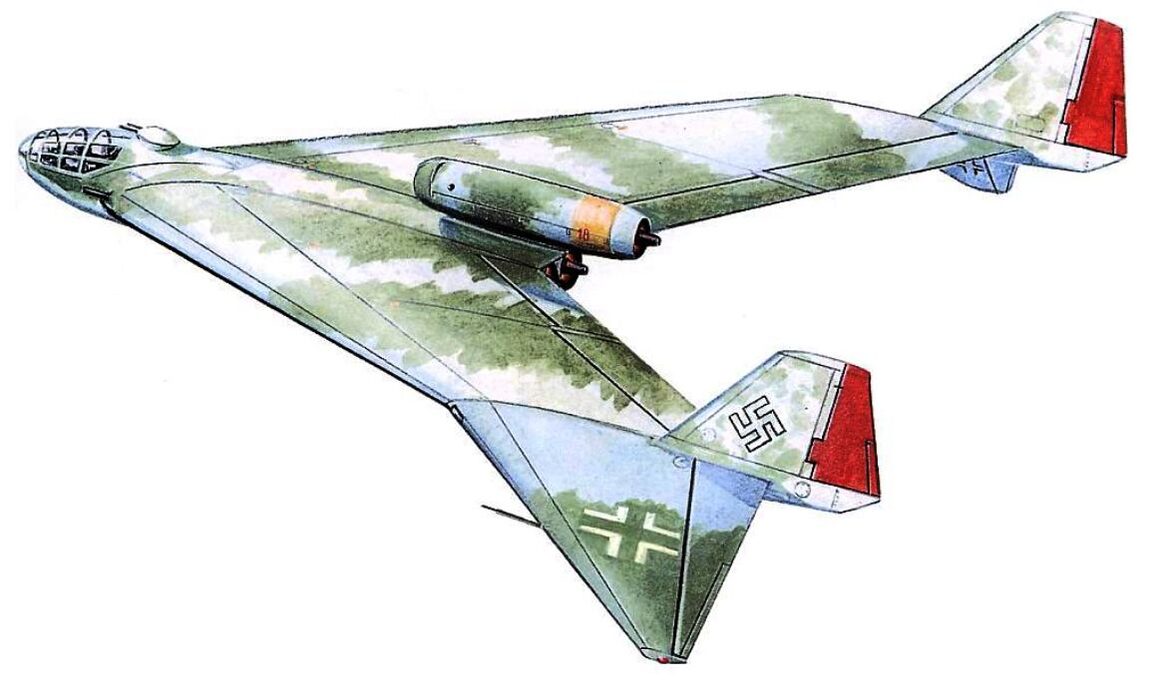

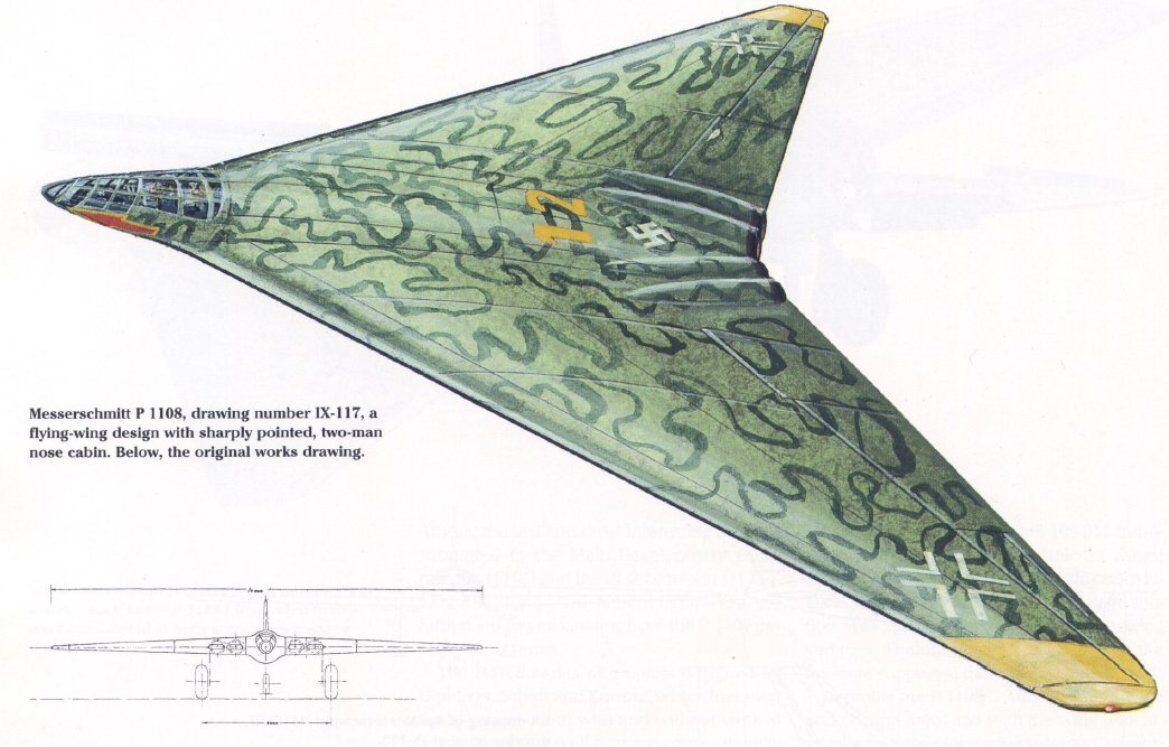

The Messerschmitt P.1108 Fernbomber was a design for a jet-propelled bomber developed for the Luftwaffe by Messerschmitt during the last years of the Third Reich.

The P.1108 was designed by Dr. Wurster, to a concept by Dr. Alexander Lippisch.

Not much is known of this variant, other than it was of a delta flying wing layout.

Four He S 011 turbojets were buried in the rear wing, each with it's own intakes under the leading edge and ducting through it.

Fully loaded weight was to be 30 tons, and range of 7,000 km [4,300 m] at a speed of 800–850 km/h [500–530 mph] and a height of 9,000–12,000 m [30,000–39,000 ft].

A crew of two was envisioned and the bomb load was to be 2,500 kg [5500 lbs].

While the Fedden Mission was told about the project, none of the information provided by Messerschmitt's employees could be independently verified, since all data had already been removed by the French.

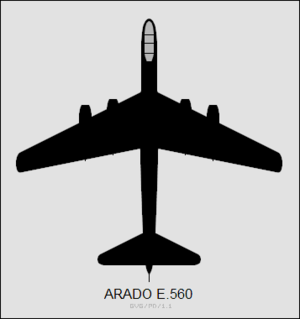

The Arado Ar E.560 part of the propaganda-based Wunderwaffe concept, designed as a fast, medium-range tactical bomber.

It encompassed several different designs, mainly differing in engine number and type.

Since the design work was submitted in the closing days of WWII, only a few incomplete documents have survived.

For the most part, the Arado Ar E.560 had swept-back wings, standard tailplanes and vertical fin and all versions had a tricycle under-carriage.

All versions also featured a pressurized cockpit located in the fuselage nose for a crew of two.

Additional equipment included two one-man life rafts, automatic course correction and control, and a variety of radio equipment.

Some designs also had remote controlled armament.

The Arado E.560 designs were a development based on the Arado 234, and they share some characteristics with that plane.

None of the projected bombers were built, as the project took place near the end of the Third Reich and was terminated by the end of the war in Europe.

Variants.

Ar E.560 2 - Four-engined bomber project, powered by four-row radial propeller engines

Ar E.560 4 - Four-engined bomber project powered by turbojet engines.

Ar E.560 7 - Smaller two-engined bomber project powered by turboprop engines.

Ar E.560 8 - Six-engined bomber project powered by turbojet engines.

Ar E.560 11 - Four-engined bomber project powered by turbojet engines.

Because of this the fuselage could not rotate for take-off in the usual way and instead a variable-incidence wing, originally developed for the BV 144 transport, was used.

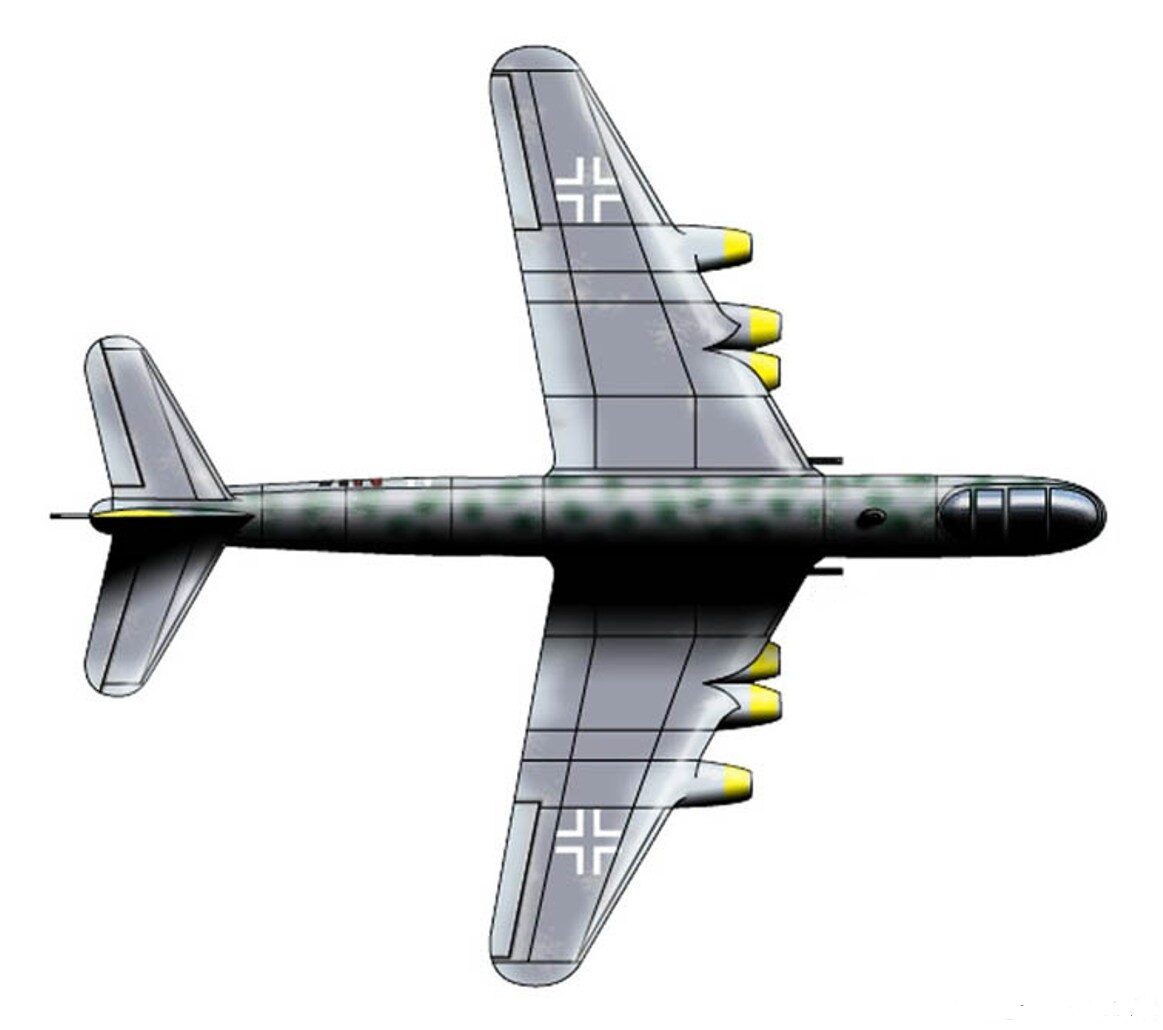

The Junkers Ju 287 was an aerodynamic testbed built in Nazi Germany to develop the technology required for a multi-engine jet bomber.

The swept-forward wing was suggested by the project's head designer, Dr. Hans Wocke as a way of providing extra lift at low airspeeds - necessary because of the poor responsiveness of early turbojets at the vulnerable times of takeoff and landing.

A further structural advantage of the forward-swept wing was that it would allow for a single massive weapons bay forward of the main wing spar.

Prior to the assembly of the first Ju 287, an He 177 A-5 [designated as a 177 prototype, V38] was modified at the Letov plant in Prague to examine the technical characteristics of this single large bomb bay design.

The 287 was intended to be powered by four Heinkel-Hirth HeS 011 engines, but because of the development problems experienced with that engine, the BMW 003 was selected in its place. The second and third prototypes, V2 and V3, were to have employed six of these engines, in a triple cluster under each wing.

Both were to feature the all-new fuselage and tail design intended for the production bomber, the Ju 287A-1. V3 was to have served as the pre-production template, carrying defensive armament, a pressurised cockpit and full operational equipment.

These included the Ju 287B-1, seeing a return to the original powerplant choice of four 1,300 kg [2,900 lb] thrust HeS 011 turbojets; and the B-2, which was to have employed two 3,500 kg [7,700 lb] thrust BMW 018 turbojets.

While the Heinkel turbojet was in the pre-production phase at war's end, work on BMW's radical and massively powerful turbine engine never proceeded past three barely-tested prototypes.

Was the Amerika Bomber technically possible during the period of WWII?

Documents from Junkers archives indicate the Ju390 could have reached New York in January 1944, but not with any useful bombload.

A Biography of Air Marshal Erhard Milch by David Irving notes that Milch favoured operating a New York mission by refuelling in Greenland

Though much has been made about the Junkers Ju390 which twice made flights to America’s east coast during WW2, this aircraft was extremely slow and limited in fuel consumption by the two-stage superchargers on BMW801E engines to a practical ceiling of just 21,000ft, much too low to survive air defences around New York.

When the Americans captured a Ju290 [surrendered to them at Munich] renamed 'Alles Kaput' and flew it across the Atlantic to USA it was noted how slowly the aircraft flew.

The Ju290 was the four engined predecessor of the Ju390

One of the Ju-390 Junkers test pilots, Flugkapitän Hans Werner Lerche referred to the Ju-390 as suffering from wing flutter in any but the shallowest of turns, thus it could not evade fighter defences on a bombing mission.

The Ju390 was, however, an exceptional long range transporter. Ju390 test pilot Flugkapitän Hans Pancherz flew one to South Africa and back, via the Spanish port town of Villa Cizneros [modern Dhakla].

The second of at least three Ju-390 built appears to be located in waters off Owls head where it went down, apparently on fire during a Hurricane in September 1944.

In September 1969 the "Daily Telegraph" newspaper published an article on the New York flight citing an interview with Junkers Test pilot Hans Pancherz who said he flew ''one of the Ju-390 transports'' [plural] on a test flight to South Africa and back in early 1944. Flughauptman Pancherz also said in the interview that the Ju-390 was specifically designed for the New York bombing mission.

He said the V1 plane which he flew was burned to prevent it falling into Allied hands. Pancherz also implied another Ju-390 aircraft existed. It appears cancellation of the Ju390 V3 bomber aircraft for the New York bombing mission was not because the wings were too weak as is cited by authors of “Die großen Dessauer,” Günther & Ott.

It is obvious from dissecting the mission fuel requirement that probably the Ju390 could not carry a viable bomb load for New York. The V3 aircraft was flown to Japan which expressed an interest in 1943 to acquire the bomber version and produce it in Manchuria.

A number of people such as Reichs Minister Speer and Flug Hauptman Lerche claimed a Ju390 was flown to Tokyo in January 1945.

Missions flown to Japan were the preserve of Sonderkommando Nebel. Reichs Armament Minister Albert Speer said the Ju390 mission to Tokyo in 1945 was flown by test pilots, not millitary service pilots.

Evidence for Nazi airfield in Greenland

The Germans are known to have operated weather stations in Greenland, however American units sent to eliminate these operations came under attack in December 1944 from two German bombers believed to be He177 aircraft.

On 15 December 1944 Swedish newspaper "Sud Svensk Dagbladet Snällposten" carried a Reuters report about fighting on land in Greenland between US and German forces. During one such skirmish the Americans were attacked by two-engine bombers which indicates a German airfield on Greenland [Report, ABC, Madrid, 15.12.1944].

It may therefore be that the germans intended for a long range type to land and refuel in Greenland on a return flight or even perhaps on the outbound flight?

Ju390 Bomber version

There was a Bomber version of the Ju390 recorded in Junkers archival material and reports were found describing actual flight testing of this bomber version, however the aircraft which reports alluded to has never been found.

German Armaments Minister Albert Speer wrote in his memoirs that at least one Ju-390 was flown to Tokyo in January 1945. Japan was interested in 1943 to acquire the type.

The Ju390 flown at Reichlin in February 1945 and seen at Prague could not have been the aircraft flown to Japan, suggesting the existence of two Ju390 in February 1945. The fuel load of the bomber version was described in September 1944, had 40,700 Litres.

Recertification at a higher 80,500kg take off weight in April 1944 may just have made the New York mission possible.

Two known Ju390 Examples

The Ju390 V1 prototype [RC + DA] was parked up and abandoned at Dessau in November 1944 where it was photographed stripped of propellers. This aircraft was torched in January 1945.

After destruction of the derelict Ju390 at Dessau there are at least three further historical sightings of a Ju390. Two Ju390 test flights at Rechlin were recorded in the log-book of Oberleutnant Fritz Eisenmann for March 1945. The first flight was for pilot familiarisation, the second for transfer of the aircraft from Reichlin to Larz.

A 1945 report of the interrogation of an SS officer, archived at the Berlin Document Centre states a Ju390 in Swedish markings took off from Schweidnitz near Breslau, Silesia in April 1945 bound for Norway.

Specifically:

"SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Schuster was an officer of SS-RSHA Abt.III. From 4 June 1944 he was responsible for transport with SS-ELF [Special Evacuation Commando].

"The Commando performed transport duties under the cover name 'Agricultural Fertilizers-Oskar Schwartz & Son'. It is cited in the Berlin Document Centre's officer service sheet.

"From this it appears he was also at the 'Special Duty Office', SS-WVHA Amt A-V zbV. In his interrogation, he told Allied investigators that in the second half of April 1945 a Junkers Ju390 aircraft of KG 200 took materials related to the 'Chronos' and 'Laternenträger' projects to Bodo airbase in Norway. Schuster stated 'the aircraft was painted pale blue and bore Swedish Air Force markings.

'As far as I remember it took off from the airfield close to Schweidnitz [Swidnice] near Fürstenstein [Ksiaz]. Before the flight it was heavily guarded by SS and covered with canvas. In Norway the transport was supervised by SS-Obergruppenführer Jakob Sporrenberg'.

The arrival of a Ju390 at el Palomar air base was also cited from an Economics Ministry document at hearings by CEANA, the Argentine Congressional Committee enquiring into Argentina's Nazi connections post-war. This alleged that regular flights occurred between Spain and Argentina from 1943 to 1945, flown via Vila Czneros on the Spanish Sahara coast.

The document cites the arrival of a multi-engined German aircraft at a private aerodrome near Puntas de Gualeguay, Entre Rios province, in May 1945, carrying laboratory equipment referred to as a “Bell” linked to Kammler's Polish project. References to a “Bell” science project in Silesia did not become public knowledge until 1998, but archived secret Argentine documents referred to it as early as 1945. This appears to be a high voltage device used for nuclear physics experiments.

From this landing in Argentina the Ju390 finally flew east across the Rio Uruguay to land at a German owned ranch 60km east of Paysandu city near the village of “19 de Abril” where it was broken up. Parts were dumped in Rio Uruguay.

The Ju390 V2 [GH+UK] meanwhile was apparently the aircraft flown to within 12 miles of New York from France in January 1944. According to Pancherz the Ju390 type was recertified in April 1944 from 75,500kg MTOW to 80,500kg.

Debate rages with some insisting only one Ju390 ever flew, but several facts challenge that view. The aircraft marked GH+UK is visibly different in proportions from the Ju-390 V1 marked as RC+DA.

The aircraft found in waters off Owl’s Head, Maine must have been either the V3 or the V4 prototype. Junkers was paid in September 1944 by the Luftwaffe Quartermaster General for six completed Ju390 airframes [source author Geoffrey Brooks, Argentina] from the V2 to V7 protypes inclusive. This payment is recorded in a contract let for series production of the Ju390 in September 1944.

A report dated March 1944 indicated Junkers Dessau would turn out 26 examples of Ju390 by March 1946. The Luftwaffe series aircraft were referred to as A-series and examples for export to Japan were termed as B-series. The Luftwaffe Quartermaster General on 1 December 1943, referred to the V2 aircraft as the first series production Ju390 aircraft. Plans for series production Ju390-A appeared with the contract issued in Septemer 1944.

All bomber production was halted by orders of Herman Göring 3 July 1944, however the Quartermaster General of the Luftwaffe issued a new contract to build a bomber version of the Ju390 in September 1944, after bomber construction were supposedly halted

A Japanese airbase on Matua Island in the Kurils is today littered with German fuel drums dated from 1943 and German manufactured electrical transformers. It may be that this was the eastern terminal of an air bridge performed by Ju-290/Ju-390 aircraft from Norway.

The main drawback of the Ju390 however according to authors Günther & Ott was that the wings were not strong enough to support the weight of air launched parisite aircraft/glide bombs like the Me-323.

Göring planned to use these with suicide pilots to deliver a small nuclear weapon to New York. The weapon in question had a 5kg sub critical nuclear device described in the famous Stockholm signal to Japan, sent between the Japanese embassy in Sweden & Tokyo 9 December 1944 describing the German “Uranium atom smashing bomb”

Air Marshal Erhardt Milch favored staging a New York attack through a refuelling airfield in Greenland. There are photos in existence of a Ju-390 on an airstrip in far northern Greenland.

Ju390 Fuel Range

Ju-390's BMW801 engines performed in context of it's maximum fuel capacity [40,700L]. Flying altitudes up to 12,000 feet the Ju-390 could range 5,850nm consuming 1,650 litres/hour.

Climbing above 20,000ft Altitude caused the two stage supercharger to burn fuel excessively. The BMW801E was however geared to delay the Supercharger to higher altitudes.

The New York Flight took 32 hours and at 1,650 L/hr this equates 52,800L, or 12,100L more fuel than a Ju390 carried in wing tankage.

It is known that both the Ju290 and Ju390 were capable of carrying extra auxilliary tanks inside the cabin, however whilst the New York flight was feasible with extra fuel tanks, this meant there was no payload, or bombload.

Any attack upon New York was either a one way flight or had to stage a landing in Greenland. Likewise flights to Japan probably required an intermediate refuelling stop.