- MAIN INDEX: Adolf Hitler Death and Survival: Legend, Myth and Reality

- The Final Years of WWII

- "Operation Paperclip" and Underground Bases

- How the Nazis planned a Fourth Reich...in the EU

- The Great Patents Heist in Germany after WWII

- Did Hitler Have Only One Testicle?

- Argentina

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 1

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 2

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 3

- The "Race" to the Moon"

- Wunderwaffen

- Hans Kammler

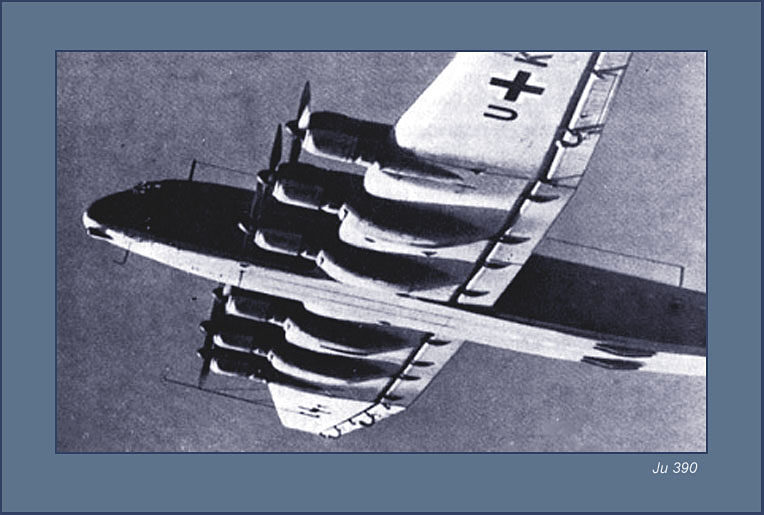

- Junkers Ju 390

- Mysterious German Bombs Aircrafts, and Carriers

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 1

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 2

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 3

- Die Glocke

- "Sweats"

- Hitler's Vergeltungswaffen

- The Coming of the 4th Reich

- “We can still lose this war” - General George Patton

- German "Super Science"

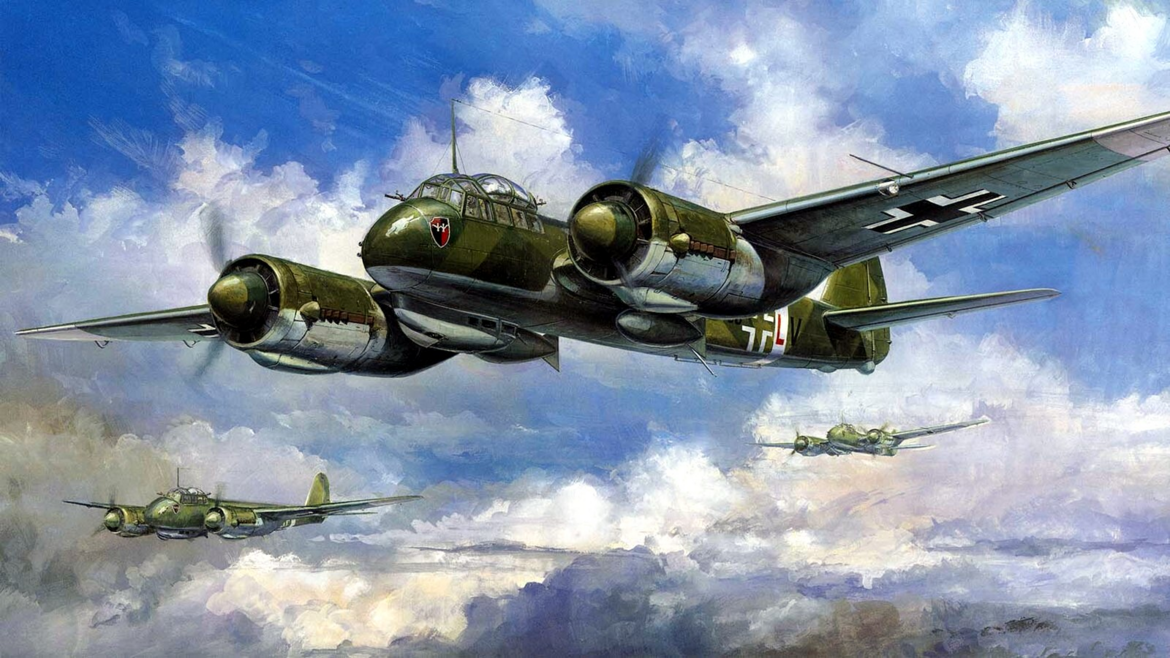

- Amerika Bombers

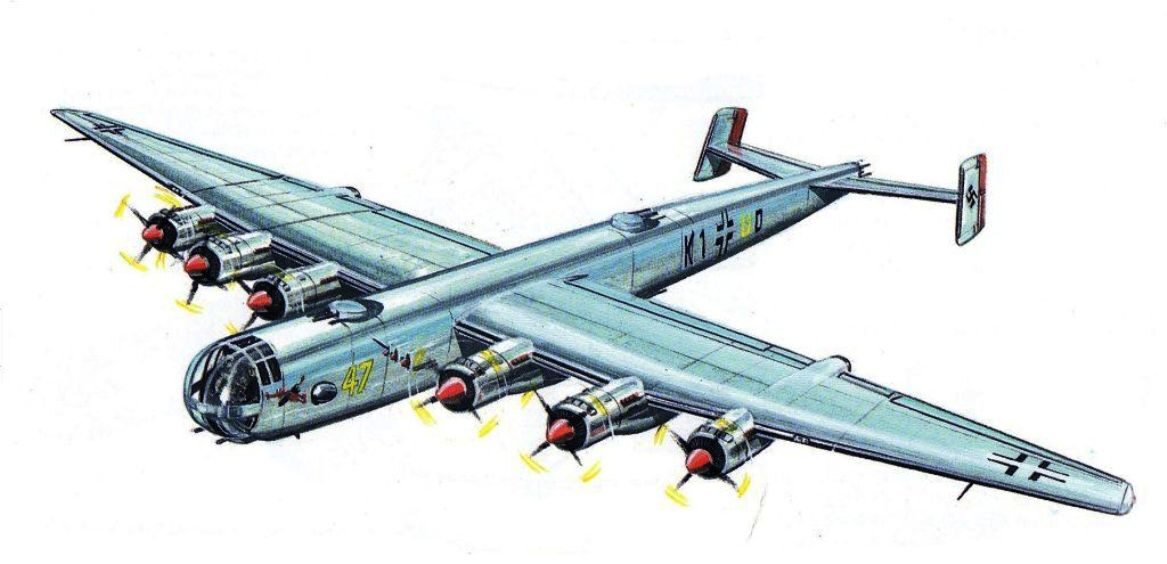

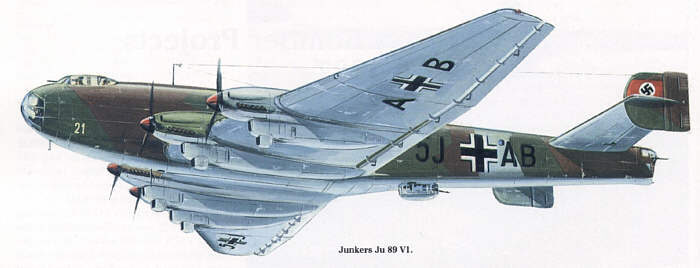

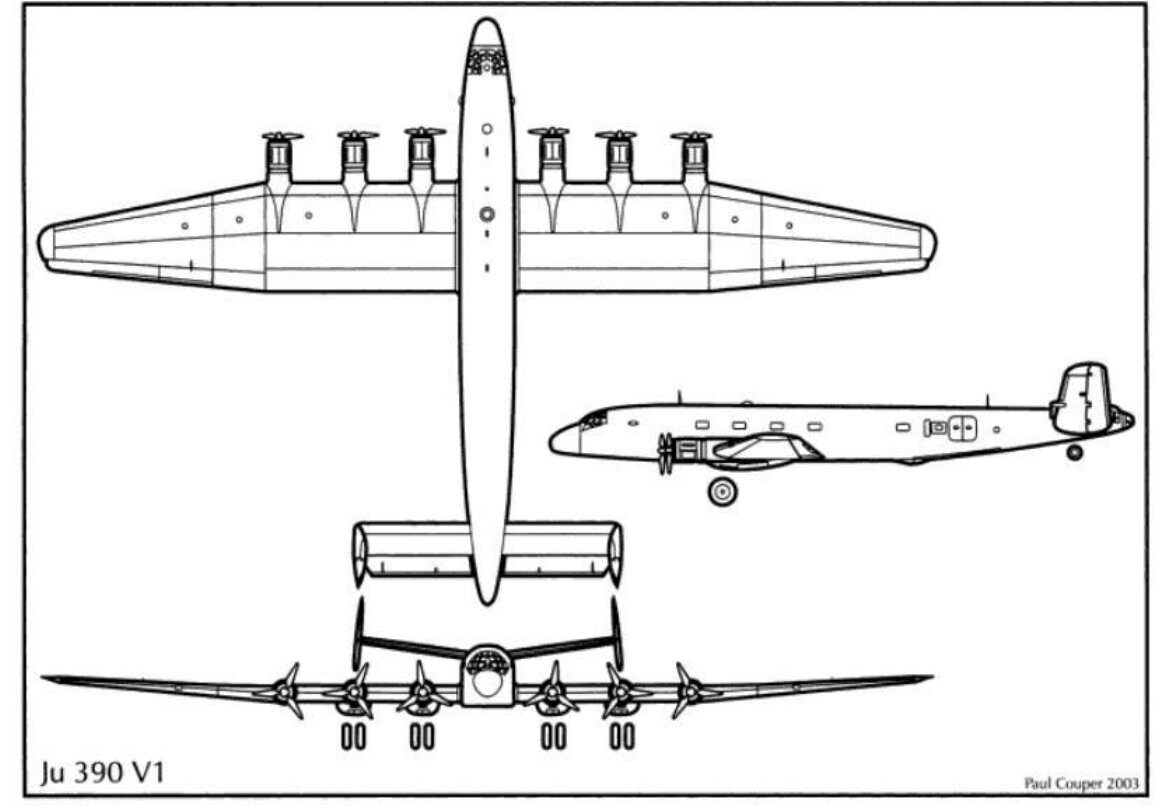

The Junkers Ju 390 was a German aircraft intended to be used as a heavy transport, maritime patrol aircraft, and long-range bomber - a long-range derivative of the Ju 290.

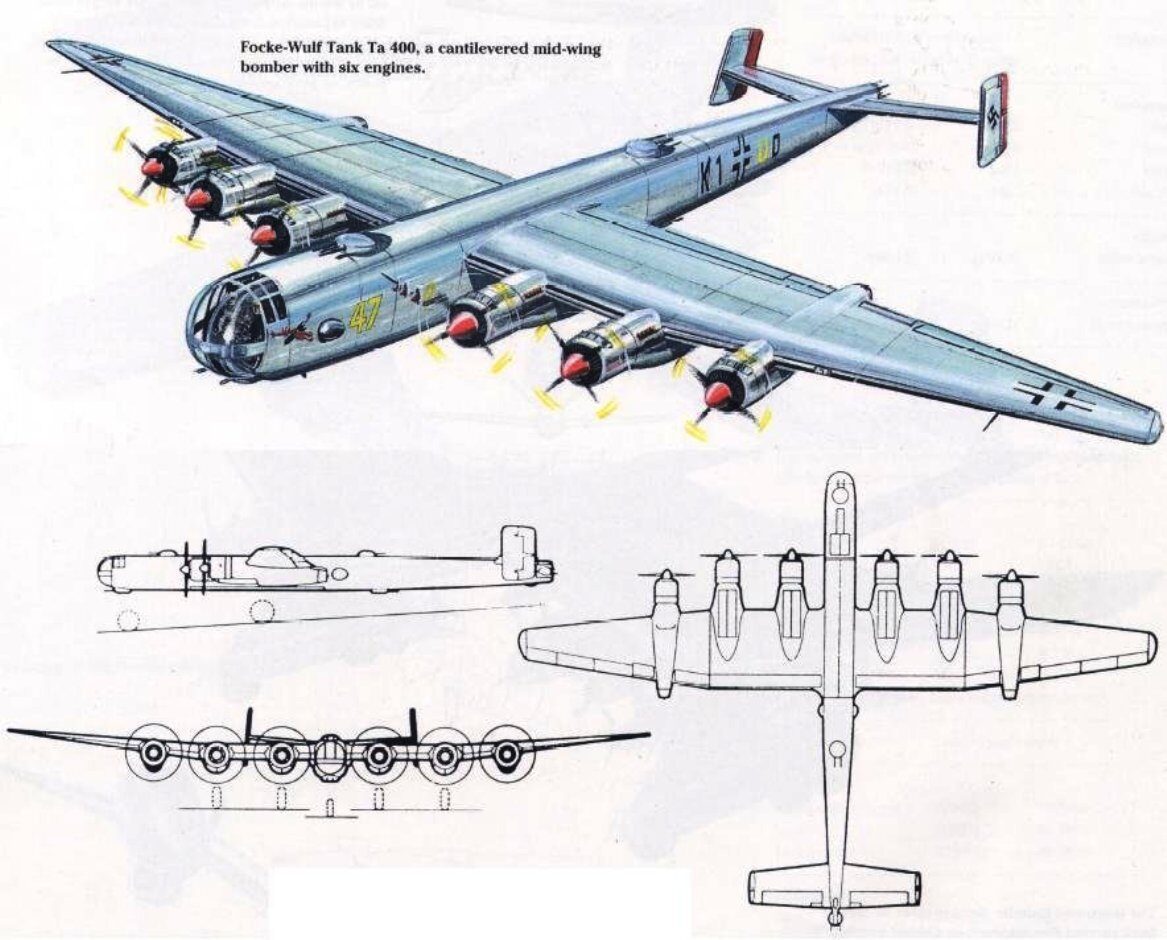

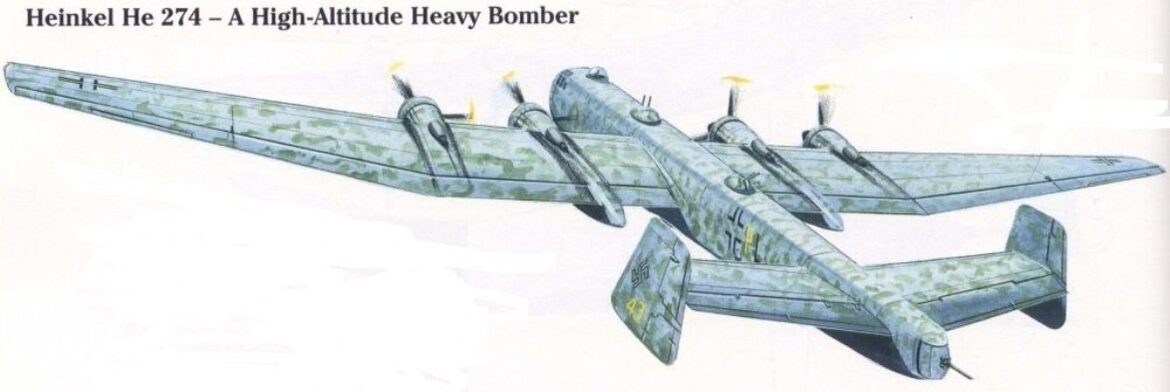

It was one of the aircraft [with the Messerschmitt Me 264, Focke-Wulf Ta 400, and Heinkel He 277] submitted for the abortive Amerika Bomber project.

Junkers chose the most simple path, enlarge the Ju.290 with six engines.

Since the majority of components for construction came from elements of the Ju.90 and Ju.290, the first flight of the Ju.390 took place as early as 1943.

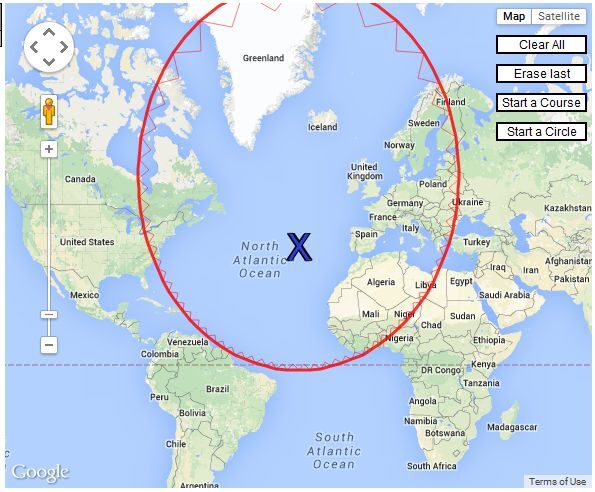

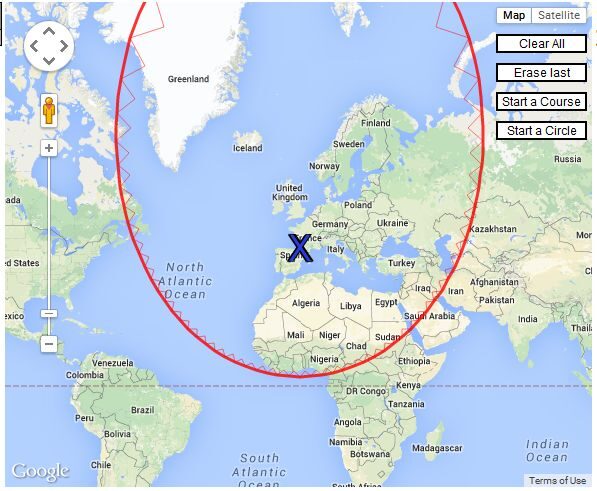

The Ju 390 was claimed to have made a test flight from Germany to Cape Town, and another from France to a point 19 km off the US east coast in 1944.

Tthe Japanese Army Air Force also considered the Ju 390 for its potential for striking the U.S. west coast.

Detailed manufacturing drawings were scheduled to be handed over to Japan in 1945.

However, at the end of 1944, the Ju.390 program was cancelled on the orders of RLM for allocating design time to other more pressing projects.

___________________________________________________________________

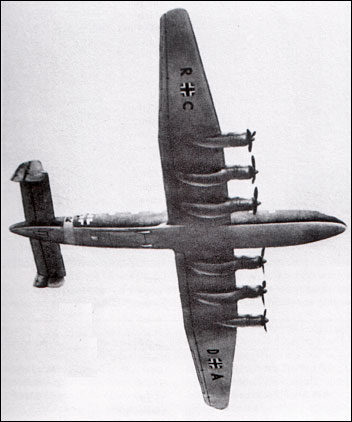

The Ju-390 traces its lineage through development of Ju-290, Ju-90 and Ju-89 types. Two prototype aircraft were flown. A third prototype was built and paid for.

Indeed, Junkers received payment on 29 June 1944 for seven completed prototypes.

It wouldd not even be known a second prototype flew except that a British Merchant Marine sailor in the Mediterranean in 1943 snapped a photo of the aircraft attacking his ship, now known by its registration, RC+DA.

Such was the long range capability of the Ju-390 that it quickly found a niche for special missions.

A second Ju-390 prototype is highly disputed and dismissed by many historians, however strands of evidence for its existence cannot be explained by conventional historians.

The fate of this second prototype is shrouded in mystery and remains at the heart of many conspiracy theories.

After World War 2, Argentina's secretive Government was compelled at Argentina's own congressional hearings to declassify some of it's wartime dealings with Nazi Germany.

Out of this tumbled the fact that a large multi engined German aircraft flew to El Palomar airbase Buenos Aires on 2 May 1945 from Villa Cisneros [now known as Daklha] and unloaded a device simply called the Bell.

The so called Bell itself is another aspect of history shrouded in disinformation.

How do we know this aircraft which arrived in Argentina on 2 May 1945 was a Ju 390 and not some other type

The Berlin Document Centre has the interrogation report of SS Hauptsturmführer Rudolf Schuster who witnessed the Bell device being loaded into a Ju 390 at Bystrzyca Klodzka airfield in April 1945 for an evacuation from Germany. Schuster asserted that it flew from there to Bodo, Norway.

Post war SS Lt Gen Dr. Hans Kammler's deputy in charge of the Skoda works, Dr. Wilhelm Voss was interviewed by British journalist Tom Agoston.

Voss claimed that the Ju-390 was used to evacuate a centrifuge which ionized mercury called the Nazi Bell, from Silesia to Bodo Norway.

Bodo at the time was home to a unit of Stuka dive bombers and some Ju-88 aircraft. It's runway was built on a flat marshy peninsula with wooden planking.

The runway there was relatively short, but given the Ju-390's eight main wheel undercarriage and considerable wing area, not an impossible airstrip for the Ju-390.

An SS report held at the Berlin Document Centre states that this second Ju-390 prototype was at Schweidnitz near Breslau in April 1945 for the evacuation of Kammler's Bell project.

The aircraft is also mentioned flying from Prague to Opole airfield near Ludwigsdorf and departure to Bodo with the so called Bell device accompanied by Herbert Jensen, Hermann Oberth and Elizabeth Adler.

Information about the Nazi Bell was not in the public arena until Polish wartime records were declassified in 1998.

A wartime service course sheet [available at Berlin Document Centre] for SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Schuster attached to SS-WVHA Amt-V zbV refers to Ju-390 operations in 1945.

This officer stated that in the second half of April 1945 a Junkers Ju 390 attached to KG 200 was at Schweidnitz [an airfield SW of Breslau] where it loaded materials from a secret project coded "Cronos/Laternenträger."

This report says the aircraft was painted pale blue and had Swedish AF markings.

It was guarded by SS and concealed beneath tarpaulin. It is known to have taken off for Bodo in Norway, but nothing further is known of its activity.

The Nazi Bell is also mentioned in Argentine wartime Intelligence reports. These reports refer to "a multi-engined German transport aircraft" at Gualeguay, Entre Rios in May 1945.

This document describes the laboratory equipment known as "the Bell" aboard the aircraft, and its purpose.

The information about the Bell did not become public knowledge until 1998, when the Polish archives released certain information about the Bell experiments which matches precisely the Argentine description of that device.

Unfortunately the Nazi Bell project has attracted support from people who wish to link it with bizarre claims of UFO sightings and this has detracted from objective treatment of the fundamental underlying truth about the Bell's existence.

In Igor Witkowsk's "Pravda o Wunderwaffe", Warsaw 2000, it is stated that there are Polish depositions extant in the proceedings against Gruppenführer Jakob Sporrenberg which indicate that "Cronos/Laternenträger" was a project in plasma physics.

The experiments involved counter-rotating at very high speeds containers of mercury and other heavy metals, gases, etc within a ceramic cover 2.5-metres tall x 1.5 metres diameter base known as "the Bell".

In "Nazi Bariloche" by the Argentinian author Abel Basti states that he has been shown a certain Argentine Intelligence document.

This declassified paper from 1945 reported that a German six-engined transport aircraft landed "at the war's end" on a German ranch at [Puntas de] Gualeguay in Paysandu province,Uruguay and had aboard items of highly secret technological equipment including a device known as "The Bell".

It is stated that the latter then came into Argentina and finished up at a German lakeside laboratory near Bariloche whose ruins are still visible and where AEG made further experiments postwar.

Declassified Argentine documents are not easily available to non-nationals and are closely guarded by those who do have them.

It is possible that a Ju 390 with assisted take-off, and mid-air refueling from a Ju 290 or BV 222, could have made the flight from Norway to Uruguay without a stop.

Whether SS-General Kammler might have been aboard the Ju 390 referred to, it is known that as Head of the V-Weapons project, Kammler oversaw this project.

He was frequently at Gross-Rosen concentration camp which supplied labour for an immense underground construction in the Eulengebirge Mountains and was linked by a long subterranean tunnel to the underground galleries at Waldenburg where "Cronos/Laternenträger" experiments were run.

The existence of this complex is confirmed in a document dated Warsaw 6 May 1947 "Action for De-Arming Oder Line" which speaks of the removal of huge quantities of machinery from the interior of the location before it was destroyed by explosives.

The last communication from Kammler is a cable timed at 1100 on 17 April 1945 addressed to SS-Führungshauptamt/Org. Abt.ROEM1 which reads:

"Re: Lorry Junkers

In accordance with Führer-Order jet aircraft measures take precedence over military. Have therefore not been in the position to release the lorry you require. Bau-Insp etc, signed Kammler".

This cable does not take us much further towards a solution of the mystery regarding Kammler except to say that it must have been a truly unique Junkers lorry to have been at the heart of so much interest.

Design and development

Two prototypes were created by attaching an extra pair of inner-wing segments onto the wings of basic Ju 90 and Ju 290 airframes, and adding new sections to lengthen the fuselages.

The first prototype, the V1, was modified from a Ju 90 V6 airframe

It made its maiden flight on 20 October 1943 and performed well, resulting in an order for 26 aircraft, to be designated Ju 390 A-1.

None of these were actually built by the time that the project was cancelled [along with Ju 290 production] in mid-1944.

The second prototype, the V2 [RC+DA], was longer than the V1 because it was constructed from a Ju 290 airframe [using the fuselage of Ju 290 A-1..

Interestingly the photo snapped of RC+DA was taken during an attack on a Malta Convoy in 1942, suggesting this aircraft was possibly operated by LTS.290 in North Africa.

The photo clearly shows a white "Afrika" band used for identification of German aircraft operating in the Mediteranean, or North Africa.

The photo was taken by merchant seaman Ron Whylie whilst his convoy KMF-5 was under attack in late 1942.

The date alone disrupts claims that the first J-390 flight was made in 1943.

A copy of his photo of RC+DA was long held by the Museum in Vienna and published by German test pilot Hans Werner Lerche in his own autobiography.

Lerche confirmed the aircraft RC+DA was indeed a Ju-390 aircraft.

Many critics have attempted to dismiss the image of RC+DA as a photo-shopped image of a Ju-290 but provide no evidence for their claim.

The maritime reconnaissance and long-range bomber versions were to be designated the Ju 390 B and Ju 390 C.

The bomber could have carried the Messerschmitt Me 328 parasite fighter for self-defense, and some test flights are believed to have been performed by a Ju 390 prototype equipped with the anti-shipping Fritz X guided glide bomb.

The Ruhrstahl Fritz-X, designed by a team under Dr. Max Kramer of the German Aviation Research Institute [Deutsche Versuchsansalt für Luftfahrt, or DVL] in 1939, reached operational status in the summer of 1943.

The Ruhrstahl Fritz-X, designed by a team under Dr. Max Kramer of the German Aviation Research Institute [Deutsche Versuchsansalt für Luftfahrt, or DVL] in 1939, reached operational status in the summer of 1943.

The Fritz-X was based on the 1,400 kilogram "PC-1400" hardened armor-piercing bomb, with four stubby fixed wings arranged in a cruciform pattern around the bomb's center of gravity.

The box-shaped 12-sided tail framed vertical and horizontal fins.

The fins had spoilers mounted on them to provide aerodynamic control, with the fins actuated by solenoids to pop them in and out of the airstream at a rate of ten times per second.

The Fritz-X did not have a boost motor, but a tracking flare was fitted in the tail.

A total of about 2,000 Fritz-X bombs were built, with 200 used in combat.

Further work focused on development of a wire-guided and then a spin-stabilized version

These efforts were cancelled, as increasing Allied pressure on Germany meant that more emphasis had to be placed on defensive rather than offensive weapons.

There are large gaps in the published information on the Ju 390, a development of Junkers' previous Ju 290 series, which themselves were extensions of the Ju 90 design.

In William Green's "Warplanes of the Third Reich" there is a detailed description of the modifications made to transform existing Ju 290 airframes to Ju 390 standard and lists the equipment they carried.

References are an issue, there is just not that much material on the Ju 390. Fortunately, most of the design details were consistent with the Ju 290s, and much of the operational history of the Ju 390 V2 parallels the 290s which were operated by the same units.

There are several wild tales involving Ju 290s and 390s floating around the Internet. All have proponents and detractors.

Many reports appear plausible, while a few live very far down Conspiracy Lane, but it is doubtful the Ju 390s simply flew a few test flights and then did nothing else, but we may never know all the details of their actual activities.

There are only a half dozen published pictures of the V1, and just one purporting to be the V2, not matching the general description of the V2 given by Green.

V1 [factory code GH + UK] - This was the development aircraft for the transport version.

Some sources state that a Ju 90 was used as the basic airframe for the conversion, and the fuselage had round cabin windows consistent with this.

The fuselage aft of the wing was extended 8.07 feet, and the wings were extended 27.23 feet, bringing the total span to 165.02 feet.

This aircraft appears to have spent its days conducting various tests and trials, including serving as an aerial tanker for Ju 290s. It ended the war on an airfield in Czechoslovakia, without propellers.

V2 [factory code RC + DA] - This was the development aircraft for the maritime reconnaissance version.

The main structure was modified the same as the V1, except an additional 8.2 foot section was added to the forward fuselage.

This aircraft was fitted with a ventral gondola, FuG 200 radar, and full defensive armament.

It was completed in October of 1943, and according to the book "German Aircraft of the Second World War" by J. R. Smith and Anthony L. Kay, the Ju 390 V2 went in January 1944 to FAGr 5 at Mont-de-Marsan for operational evaluation, from where it made a claimed flight to within 12 miles of New York.

FaG 5 was disbanded in August 1944 [to reform later on Ar 234s] when German airbases in France were threatened by the Allied advance. FaG's Ju 290s were passed to KG 200, a Luftwaffe special missions unit.

Several interesting missions are attributed to the Ju 390, including liaison flights to Japan.

While confirmation is lacking [not surprising for KG 200, a special ops unit)] Ju 290A-9s are known to have completed many of the same assignments.

The V2 was standing by at Rechlin to evacuate Nazi VIPs to Spain in April of 1945.

While a Ju 290A-5 [W.Nr. 110178] actually made the flight to Spain, the V2 was not reported to have been located after the war.

One account says the V2 was flown to Norway, where it was repainted in Swedish colors, and then used to transport German scientists to a ranch in Paysandu Province, Uruguay.

The aircraft was then reportedly dismantled and sunk in the Rio Uruguay River, where it is said to remain to this day.

V3 - This was to be the Amerika Bomber Ju 390A development aircraft, but it was never built. Dimensions were to be the same as the V2, but defensive armament was to have been increased. The bomb load was to have been carried externally.

A Luft '46 project is a proposed reconnaissance version with wings extended to 181.63 feet.

This was a Paperwaffe project only, and not even general configuration drawings have been found.

Ki-390 - This one is definitely a Nippon '46 "what if". Considerable interest in the Ju 390 design was expressed by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, the JAAF even purchasing manufacturing rights. However, the design was never developed.

Operational history

V1

The V1 was constructed and largely assembled at Junkers' plant at Dessau, Germany, and the first test flight took place on 20 October 1943.

Its performance was satisfactory enough that the Air Ministry ordered 26 in addition to the two prototypes. However, the contracts for the 26 Ju 390s were cancelled in June 1944 and all work ceased in September of that year.

Hans Werner Lerche records his flight in the Ju-390 on 28 October 1943, but makes no comments about this flight at all which is rather surprising if one is asked to accept this was either, the Ju-390's maiden flight, or for that matter personally his first flight in the type. Rather it tends to suggest that he had flown the type before.

Lerche later disclosed that the Ju-390 was not unpleasant to fly however it could not be flown too fast or turned too quickly otherwise it had a flutter problem. He said it was very stable and slow flying aircraft.

On 26 November 1943, the Ju 390 V1 - with many other new aircraft and prototypes - was shown to Adolf Hitler at Insterburg, East Prussia.

According to former Junkers test pilot Hans-Joachim Pancherz' logbook, the Ju 390 V1 was brought to Prague immediately after it had been displayed at Insterburg, and while there took part in a number of test flights, which continued until March 1944, including tests of inflight refueling.

The Ju 390 V1 was returned to Dessau in November 1944, where it was stripped of parts and finally destroyed in late April 1945 as the American Army approached.

The conventional view of the Junkers Ju-390 story hold that only one prototype was ever built, being the Ju-390 V1. This version asserts that the Ju390 V1 was first flown from a dirt airstrip at Merseberg on 20 October 1943, piloted by civilian Flugkapitän Hans Joachim Pancherz and engineer Dipl-Ing Gast.

However there is also an earlier claim that the Ju-390 made it's first flight in August 1943 at the hands of famous Reichlin Test pilot Flugkapitan Hans Werner Lerche at Bernberg.

The conventional view therefore is that the Ju-390V1 was retired from service and flown to Dessau in November 1944 where it was stripped of propellers and sat derelict until destroyed. There are conflicting claims of it's destruction by a US 8th Air Force raid on 16 January 1945 and other claims that it was burned in April 1945 to prevent capture.

Either way it is generally accepted the Ju-390 V1 ended its career at Dessau in November 1944 and remained derelict until destroyed in 1945. RC+DA appears to have been the aircraft destroyed at Dessau in 1945.

Ju-390 identities

RC+DA appears to have the shorter fuselage Ju-390 V1 and to have been equipped as a maritime patrol aircraft. GH+UK appears to have been the longer fuselage Ju-390 V2 equipped for a transport role.

Chief Test Pilot Flughauptmann Hans Pancherz told the British at a hearing on 26 September 1945, that only one prototype was built however in October 1943 Major Hoffmann from [GL/C/E2] RLM recommended that Ju-390 production should commence immediately and there was no need for further prototype aircraft. Hoffmann urged proceeding straight to series production.

Air Marshall Erhard Milch adopted Hoffmann's recommendation. The first prototype had been flying since August 1943. This aircraft displayed some longitudinal instability. The second aircraft had a much longer fuselage with a greater tail movement arm. The Ju-390 V2 was redesignated as the production standard Ju-390 A1. Junkers company records incidentally suggest the A1 aircraft did fly.

Technically Pancherz may have been telling the truth that no other prototype was built but that does not mean that no other Ju-390 was built.

His answer was misleading the British.

At the end of the war Argentine and Polish sources which until recently were classified, both record that a Ju-390 flew from Norway to Argentina and then the aircraft was ferried to a German ranch in Paysandu Province of Uruguay where it was dismantled.

Now we have evidence from multiple sources which prove that Pancherz lied to conceal the flight to Argentina.

On 1 December 1943 the Luftwaffe QM-General listed the first series aircraft Ju 390 V2 for October 1944. This machine would be available at the end of October, three more in November, five in December and so on into March 1946. Ju 390 V2 was expected to be ready by the end of September 1944 and flight tested in November. A report dated March 1944 indicates that Dessau was to turn out 26 Ju 390, another report from May 1944 that Junkers had no less than 111 on the order book.

Junkers was paid on 29 June 1944 for the completion of seven Ju-390 aircraft. Because of the general situation, all work on the production was stopped in June 1944 for the increased fighter production, the so-called "Jäger-Notprogramm".

On 29 June 1944 KdE Rechlin made a surprise announcement condemning the aircraft as unsuitable for long-distance work because the wing loading would be too great for the intended payload [various other drawbacks were also recited]. Shortly before the termination of all work Junkers received contracts in June 1944 to build Ju 390 V-2 to V-7, but this might have been done for accounting purposes.

It appears RC+DA was the Ju-390V1 and the Ju-390V2, fitted with BMW801E engines was redesignated as the Ju-390 A1. It is recorded by Junkers that the Ju-390A1 transporter was built and GH+UK was clearly the transporter version as compared with RC+DA which was clearly equipped with a bomb aimers gondola as a maritime patrol aircraft.

This type of switch happened previously when the the Ju-90 V11 was redesignated as the Ju-290V1 and Ju-90 V12 was redesignated as J-290 V2. The Ju-90 V6 airframe was itself re-designated Ju-390 V1.

The unconventional explanation for the fate of Junkers second Ju-390 prototype concerns an alleged flight from an airfield at Schweidnitz in Poland to evacuate a Bell shaped ionising centrifuge used by the Nazis for advanced research of high energy fields. This Bell device has become the subject of various claims, attracting cynicism from some and fantastic claims from others.

Not many people realise that the Ju-390 V1 prototype which first flew from Junkerswerke Dessau in August 1943 was actully the converted Ju-90 V6 constructors number J4918.

As a Ju-90, it had been registered D-AOKD and then KH+XC in Luftwaffe service until April 1942, when its Ju-390 conversion began.

The second Ju-390 V2 was apparently converted from Ju-290 A1 werke number J900155 which became RC+DA and first flew from Mersberg 20 October 1944 [sometimes also cited as Bernberg].

Oberleutnant Joachim Eisenmann flew the Ju-390 V2 twice at Reichlin on 9 February 1945.

In "Hitlers Siegeswaffen", Band 1, Friedrich Georg writes about the Ju-390 V-2. On 9 February 1945, there were two flights by Captain Joachim Eisermann in Rechlin and another from Rechlin to Lärz . Shortly after, the aircraft disappeared and was not reported as being captured.

"At his hearing before the British, on 26 September 1945, Professor Heinrich Hertel, chief designer and technical director of the Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works, stated that the Ju 390 V-2 had neither been completed nor had it been flown".

This former Ju-290, Ju-390 converted airframe has no record of ever having a service life, or registration as a Ju-290, however it does have association with a test program at Prague where the Ju-290 production line was set up.

The Ju-390 V2 had a lengthened fuselage.

Ju-390 pilot Hans Pancherz said in a 1969 interview that he flew the transport aircraft. It is known that one Ju-390 was a maritime patrol bomber fitted with FUG200 Hohentweil nose radar.

Confusion reigns as to which one was which however test Pilot Hans Pancherz in an interview by the "Daily Telegraph" in September 1969 recounting his Ju-390 flight to South Africa, mentioned that he flew the Ju-390 transport version.

Pancherz' flight in the Ju-390 to Cape Town by necessity would have involved air to air-refueling.

In January 1944 a Ju-290 A4 aerial tanker aircraft registered CE+YZ was also performing trials over the Atlantic with a Ju-390 from Mont de Marsan.

This was the same time period during which Baumgart claimed the New York flight occurred.

Pancherz has since 1969 given interviews about Ju-390 missions to a Spanish newspaper from his home in Barcelona.

There are three independent sources for a claim that the Ju-390 flew a mission from Bodo in Norway to Tokyo on 28 March 1945.

One of those sources was former Reichs Armaments Minister Albert Speer in his autobiography "Inside the Third Reich".

It is known that the Ju-390V1 marked GH+UK was flown to Dessau in October 1944 and stripped of propellers. In April 1945 it was burned to prevent capture.

The flight to Tokyo could not have occured on that date if there was only one flying Ju-390.

The second Ju-390 was flown to Argentina in May 1945 from Bodo Norway, in Sweedish airline markings.

There is evidence of this from multiple sources, but include declassified Polish files and Argentine economic files from 1945 about Nazi flights to Gualeguay, Entre Rios province.

Polish evidence suggests it was flown from Gualeguay to an airstrip on a German owned ranch at Paysandu province, Uruguay. There it was witnessed by a Polish diplomat being dismantled with parts dumped into the Rio Pirana, near Paysandú.

The flight to Argentina arrived via the Spanish Sahara airfield at Vila Cisneros.

This airport before the war was a vital refueling stopover for many airlines such as LIAT to Brazil using Italian tri-motors and Deutsch Luft Hansa to Rio de Janero.

A Japanese technical legation to Berlin in 1940 returned in June 1941 by a German military flight via Vila Cisneros to Brazil where the Japanese caught a steamer to Yokohama.

V2

A hotly contested argument rages whether a second Ju-390 prototype was ever built. This owes in part to postwar testimony at a British military hearing by Junkers chief engineer for Ju-390 production and similar testimony from the Ju-390 project pilot, Hans Jochim Pancherz who both claimed only one prototype was ever built.

There the story might have ended except that the Ju-390 V1 prototype was retired to the airfield at Dassau and stripped of propellers where it sat conspicuously derelict until destroyed there in 1945. Then Oberleutnant Joachim Eissermann recorded in his log book flying the Ju-390 V2, twice on 9 February 1945. Contrary to modern embellishments, Eissermann's log book did not record the aircraft by it's registration markings. Only that it was the V2 prototype. The first flight was 55 minutes of familiarisation flying around Reichlin air base. The second flight was a 22 minute delivery trip to Larz.

In their 1993 book, "Die Grosen Dessauer: Junkers Ju-89, 90, 290, 390" Karl Kössler and Gunter Ott suggest the second Ju-390 was not constructed and flown before September/October 1944, yet RLM cancelled all Ju-390 contracts in May 1944.

If the Ju-390 contract was canceled in May 1944, then it could not have been completed in September 1944. Kössler and Ott have gotten it wrong.

Soviet historical sources claim the unfinished Ju-390 airframe was in fact the V3 prototype. The Ju-390 V3 prototype was intended for completion in the "summer" of 1944. In fact the original RLM contract in March 1942 was let for three prototypes and we have evidence for the existence of two aircraft. What can be said truthfully is that only one Ju-390 airframe was found in Germany after the War. That is not however conclusive proof that only one was built.

The Ju 390 V2 was assembled in Bernbeg, was first flown in October 1943, and is said to have been configured for the maritime reconnaissance role. Its fuselage had been extended by 2.5 m [8.2 ft], and it was equipped with FuG 200 Hohentwiel ASV [Air to Surface Vessel] radar and defensive armament consisting of five 20 mm MG 151/20 cannon. Green notes different armament, specifically four 20 mm MG 151/20s and three 13 mm [.51 in] MG 131 machine guns.

The V2 aircraft was an unarmed transport version with a longer fuselage than the V1. It also appears to have been shortened ahead of the wing. This aircraft is reported making it's first flight from Bernberg in August 1943, flown by Flugkapitän Hans Werner Lerche.

Test pilot Oberleutnant Eisermann recorded in his logbook that he flew the V2 prototype (RC+DA) as late as February 1945. However, Kössler and Ott state that the Ju 390 V2 was only completed during June 1944, with flight tests beginning at the end of September 1944.

A Ju 390, which may or may not have been the V2, is claimed by some to have made a test flight from Germany to Cape Town in early 1944. The sole source for the story is a speculative article which appeared in the "Daily Telegraph" in 1969 titled 'Lone Bomber Raid on New York Planned by Hitler', in which Hans Pancherz reportedly claimed to have made the flight in question - in company with an air to air refueling aircraft [Ju-290 reg CE+YZ] his Ju-390 flew to Cape town and back during January 1944.

The test flight went smoothly but the operation was soon canceled due to lack of resources, said Pancherz. As with other claims of the mysterious flight, no factual data could be obtained.

Author James P. Duffy has carried out extensive research into this claim, which has proved fruitless. Kössler and Ott make no mention of this claim either, despite having themselves interviewed Pancherz.

The Ju-390 V3 may have been intended as a flying tanker aircraft for air to air refueling trials.

Such trials were conducted around Prague with the V1 aircraft in early 1944. Construction of the V3 appears abandoned in May 1944 when all production was switched to emergency fighter construction. Conventional historians who assert the existence of only one Ju-390 assert the V2 was broken up before completion. A contrary view is that it was actually the uncompleted V3 aircraft which was broken up in June 1944. By May 1944 orders had already been issued to switch all production to fighters.

On 29 June 1944 KdE Reichlin condemned the Ju-390 saying that it would be unsuitable because the wing was not strong enough for the intended 10,000 payload. That declaration is likely to require some qualification. Reichlin was testing the Ju-390 for an intended role as the Ju-390C bomber at the time to carry three Me-328 parasite aircraft.

The wing was very lightly loaded. The weight of fuel was evenly distributed across its span. On the ground it had four sets of main undercarriage. For the transport role it was likely quite strong enough. The requirements for a bomber role are quite different, such as requiring higher cruise speeds to avoid interception.

The Ju-390 had a relatively slow VMO speed of 272 knots. If flown beyond this speed it was likely to break up as would any aircraft flown in excess of design speeds. This does not imply it was unsafe below VMO.

As a slow transport the Ju-390 had extreme long range and was quite safe. If re-engined to obtain higher speeds and carrying extra weight from gun armament then the Ju-390 likely was inadequate. It was likely that the Ju-390's wing was unsuitable in a specific situation when pushed to higher speeds.

The bomber version of the Ju-390 was intended to launch either parasite fighters or large rocket powered glide bombs at New York. It was the weight of these weapons which the wing was too weak to carry. Not the fuel weight of a mission to New York.

New Evidence for Existence of a Third Ju-390

Wreckage was reported of a large six motor aircraft with very dark green and black paint in the sea off Owls Head Lighthouse, Maine about 17-19 September 1944. Three bodies were found in area on 28 September 1944 and taken by the U.S. Coast Guard to Rockland Maine Station. One of the witnesses states he saw one body in German Luftwaffe Signal Corps Uniform, [grey-blue with yellow/brown collar tabs], which suggests the rank of Hauptmann [Luftwaffe Captain].

The FBI, US Secret Service, Military Intelligence etc are all reported by locals at the time having told those who had witnessed the crash that it was first a submarine, and then later that they better forget what they saw, but the witnesses insist it was no submarine but rather an aeroplane.

A diver recovered a badly worn constructor's plate from this aircraft. It read:

RMZ WERKE Nb 135 #? 34 [Allgemeine]

JUNKERSMOTORWERKES [Agts: Haan]

FWU WERKE Nb 135 #? 34 [Gbs: Fliegeroberstkommando Rdt]

Nobody has ever bothered to investigate this sighting and the US Government went to great lengths to silence all reports of it.

Even more disturbingly Germany was working on a nuclear weapon invented by the scientists Eric Schumann and Walter Trinks for Heereswaffenamt [HWA]. In early July 1944 USA threatened Hitler though Lisbon that USA would drop a nuclear weapon on Dresden unless Hitler sued for peace within 6 weeks. Was this Ju-390 flight in September 1944 Hitler's reply?

Was there in fact a forerunner to 9/11 in September 1944 and was the world's first nuclear weapons attack hushed up?

Junkers Ju 390 "Amerika Bomber"

Adolf Hitler badly wanted to bomb New York City. The Luftwaffe also had a prime target further in on the US mainland: the major automotive plants in Michigan busy churning out four-motor bombers that were wreaking havoc on the German homeland. The generic name for development in this area was the "Amerika Bomber." Both targets were within theoretical reach by war's end, but territorial losses and industrial damage prevented these ambitious objectives from ever being realized.

The Luftwaffe had halted development of strategic bombers in the 1930s.

"The Führer does not ask me how big my bombers are, only how many I have," Hermann Göring said rather fatuously - a decision which the Germans regretted as the years passed and the Allies demonstrated the devastating power of four-engine bombers.

Some Nazi projects were attempted, but it was tough to tool up and develop a capable strategic bomber when the Allies were bombing any factories they could identify as manufacturing advanced aircraft. One project that did manage to get beyond the mere design stage, though, was the "New York Bomber".

The German designers took the basic Junkers 290 design and expanded it for the Ju 390, lengthening the wings to fit a total of six engines and lengthening the fuselage to increase the payload. It would have carried a crew of ten in full operational mode, with two 13mm machine guns in a gondola, two on the beam as in Allied bombers, and a 20 mm cannon in the tail.

The plan was to prepare it for maritime reconnaissance, bombing and transport. The engines were BMW 801D radial piston engines of 1730 horsepower apiece. These would have provided a top speed of 314 mph, better than Allied bombers and comparable to most fighters of the day, with a range of 6,030 miles and a service ceiling of 19,700 feet.

Two prototypes were built and flown. The first V-1 flight was 20 October 1943, with the second V-2 prototype also flying that month. Tests continued through mid-1944 before all Nazi bomber projects were shelved.

The Ju 390 V2 was assembled in Bernburg and was first flown in October 1943. It is said to have been configured for the maritime reconnaissance role. Its fuselage had been extended by 2.5 m [8.2 ft], and it was equipped with FuG 200 Hohentwiel ASV [Air to Surface Vessel] radar and defensive armament consisting of five 20 mm MG 151/20 cannon.

Aviation expert William Green notes different armament, specifically four 20 mm MG 151/20s and three 13 mm [.51 in] MG 131 machine guns. The Germans knew all about effect vs. ineffective bomber defensive armament by that stage of the war. The aircraft never left the prototype stage, never saw any kind of action, and were destroyed in Germany by May 1945.

There is an unproven legend that one of these V.2 flew for 32 hours and came within sight of New York City that spring before turning back to its field in France - possibly within the aircraft's capability, but highly unlikely and fiercely denied by some experts.

Other, more exotic legends such as that one actually flew over Detroit and New York are pretty much impossible, however not completely......

Disclosed in Robert Forsyth's book "Messerschmitt Me-264 Amerika Bomber" the actual proposal was for a flight from Brest in France. A captured Photographic technician, Unteroffizer Wolf Baumgart, was interrogated by the US Ninth Air Force and his testimony was recorded by the A.P.W.I.U. Report 44/1945.

Because Baumgart was from a unit at Mount de Marsan there has been an assumption that this was the actual airfield. There is also an uncorroborated claim that the flight departed Norway and passed over USA before crossing the US coast near New York to land at Mont de Marsan, so there are a smorgesboard of claims.

Baumgart claimed the flight occurred in January 1944. Two aircraft were built and flown. In October 1943 the Ju-390 V2 second prototype was re-designated as the Ju-390 A1 [first production aircraft] Junkers records disclose that the Ju-390A was flown.

After the war Pancherz claimed only one Ju-390 prototype flew, but conveniently concealed that the second prototype was redesignated as the Ju-390 A1. The Ju-390 V1 was derelict and stripped of propellers at Dessau from November 1944 yet there were numerous records of another Ju-390 flying until April 1945

The Ju-390 aircraft certainly had the ability to perform such a flight since Ju-390 pilot Hans Joachim Pancherz also made a flight to Cape Town in April 1944 and disclosed this in a 1974 newspaper article. A book called the "Bormann Brotherhood" written by a former WW2 British intelligence officer William Stevenson cited various flights to Argentina and South Africa during WW2.

As for the reason to fly as far as Cape Town, Major Herman Fischer of FAGr.5 was actually obliged by requests from Dönitz to perform numerous long range reconnaissance missions for U-boat intelligence collection.

Also in 1993 the Argentine Economic Ministry revealed classified wartime records that regular use was being made by German aircraft of Palomar airfield and that this involved trade between Germany and Argentina.

The Ju-390 was taken over and flown by KG200 in February 1944. Prior to this it was flown by Versuchsverband Obd.L on trials from Mont de Marsan and Prague Letnany airfield.

Now it is urban legend time.

These are always fun to go through because they smack of science fiction, but they have virtually no known substance. Simpy repeating these wild tales makes you sound like people who thinks that there were Nazi Luftwaffe bases in Antarctica.

The rumors of fantastic flights are true; the evidence of such flights actually taking place, non-existent. However, given the capabilities of the Ju 390, the legends are persistent, and they never die.

They could serve [and probably have at some point] as the starting points for alternative history novels. Also, with Nazi records being destroyed during the war, the way is open for all sorts of tales that the Ju 390 actually flew in 1942, that there was a fleet of them [or at least seven], and so forth and so on.

So, every claim must be treated with extreme skepticism and judged by the standard that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof..com

The first public mention of an alleged flight of a Ju 390 to North America appeared in a letter published in the November 1955 issue of the British magazine "RAF Flying Review", of which aviation writer William Green was an editor.

The magazine's editors naturally were skeptical of the claim, which asserted that two Ju 390s had made the flight, and that it included a one-hour stay over New York City. This would have required a base at least in the Azores or something of the sort, or some sort of advanced refueling capability. It also would have entailed burning up a whole lot of precious fuel that the Third Reich would have had other, vastly better uses for than circling aimlessly over an enemy city [somehow without being seen] to prove some kind of point.

In March 1956, the "Review" published a letter from an RAF officer which claimed to clarify the account. According to Green's reporting, in June 1944, Allied Intelligence had learned from prisoner interrogations that a Ju 390 had been delivered in January 1944 to FAGr 5 [Fernaufklärungsgruppe 5], based at Mont-de-Marsan near Bordeaux, and that it had completed a 32-hour reconnaissance flight to within 19 km [12 mi] of the U.S. coast, north of New York City. ]

The trial flight was made to New York carrying a dummy bomb to prove it could be done. This came from interrogation of a captured German serviceman, photo intelligence Unteroffizer Wolf Baumgart, who claimed to have seen the pictures of the Manhattan skyline. This was duly recorded in Ninth Air Force A.P.W.I.U. Report 44/1945, so it has that means the story never will die. Those who have looked into this have decided that it was "disinformation," i.e., a string of lies for some hidden purpose. A senior [unnamed] Luftwaffe figure is thrown into the mix as having separately corroborated the story.

This fanciful claim by the prisoner was rejected just after the war by British authorities. Aviation historian Dr. Kenneth P. Werrell states that the story of the flight originated in two British Intelligence reports from August 1944 which were based in part on the interrogation of prisoners, and titled "General Report on Aircraft Engines and Aircraft Equipment"; the reports claimed that the Ju 390 had taken photographs of the coast of Long Island.

These photos have never been discovered and we can assume that they in fact never existed.

However, it also has not been explained why British Intelligence came up with this story in the first place, and what interrogations it was based upon. If some German prisoner made the claim, who was it? No names have been adduced. If the report is true, that information [the interrogation report] may be sitting in some storage facility.

These wild tales go on and on. Independently, there is a probably spurious report that there was a third Ju 390 constructed which either crashed, was intentionally destroyed or simply disappeared. Wreckage was reported in 1944 of a large six motor aircraft with very dark green and black paint in the sea off Owls Head Lighthouse, Maine, but nothing conclusive is known about that supposed incident.

There is no reason to think that it was a Ju 390 aside from the basic configuration. This was about 17-19 September, 1944. Three bodies were supposedly found in the area on 28 September, 1944 and taken by the U.S. Coast Guard to Rockland Maine Station. One of the witnesses stated that he saw one body in German Luftwaffe Signal Corps Uniform, [grey-blue with yellow/brown collar tabs], which suggests the rank of Hauptmann [Luftwaffe Captain].

The FBI, US Secret Service, Military Intelligence etc reportedly told locals at the time that whatever they had witnessed was a submarine. Anyone who persisted was told that they had better forget what they saw. The witnesses insisted it was no submarine but rather an aeroplane, but followed instructions. Local Mr. Ruben P. Whittemore claims to have had relatives who eye-witnessed this event. The supposed proof ends there, though there again are unproven, fanciful tales of unexplained Luftwaffe wreckage having been found in that vicinity years later.

A Ju 390, which may or may not have been the V2, is claimed by some to have made a test flight from Germany to Cape Town in early 1944. The sole source for the story is a speculative article which appeared in the "Daily Telegraph" in 1969 titled 'Lone Bomber Raid on New York Planned by Hitler', in which one Hans Pancherz reportedly claimed to have made the flight in question.

What they would have wanted to find or do in Cape Town -a British Commonwealth nation- is a little difficult to fathom.

Hans-Joachim Pancherz was a Junkers test pilot

Given that nobody disputes Pancherz made the 11,400 nautical mile round trip to Cape Town, what grounds have doubters of the New York flight got to dispute the ability of a Ju-390 to make a simple 6,230 nautical mile flight to New York and back ?

Regarding the supposed Ju 390 flight to Manchuria, the story goes that there were problems with planning this that went beyond the merely technical. The best route, and the one initially [supposedly] considered, would have been from northern Norway east across the frozen Arctic Ocean, with a final jog south over Siberia. The Japanese, however, were practically hysterical at the thought of a Nazi overflight of Russia to Manchuria provoking Russia to declare war on Japan..

The second route would have been a southern one, slightly more direct but infinitely more dangerous, across the Caucasus from forward German bases in the Balkans or Ukraine. The plane used would had to have been a V. 2, whose range was enough to make the trip. In-flight refueling tests were made with the Ju 390, and it was at least theoretically possible to get there.

The story usually is that it was a Ju 290 that was enlarged to make trips to Manchuria under Lufthansa [German civilian airliner] markings.

If the war had continued, the JU-390 would have had major strategic implications. The impact would not have been the bomb damage caused by the craft, but from the predictable Allied response. The Americans were notorious for taking extreme security precautions against proven threats. For instance, they instituted extensive convoys and other defensive measures in response to the short-lived U-Boat operation in 1942 off the American coast [Operation Paukenschlag]. These remained in place long after the Nazi operation was discontinued in September 1942.

According to Thomas Powers's book "Heisenberg's War," the Nazis had a concrete plan to take the war to American shores if the war had lasted longer, the parasite bomber [Mistletoe] concept. Another plane, the Me 328, was designed with this specific role in mind. Plans for this tactic are said to have been hatched during a meeting between Generalfieldmarschall Erhard Milch and Generalmajor Freiherr von Gablenz at Berlin on 12 May 1942.

After release, the Me 328 pilot would release a bomb over Manhattan and then ditch at sea near a U-boat. The Me 328 thus was intended as a parasite bomber for the larger Amerika Bomber program. The small one-way plane was to be carried by or towed behind either an Me 264 or a Ju 390 to attack New York. It would be a one-way trip for the Me 328, using all of its fuel in a one-way dash to New York City or Washington, D.C., with the host Ju 390 not having to get too close to shore in order to avoid detection.

Why this could not have been done much easier with a U-Boat carrying a small plane the Japanese had lots of these aircraft carrier submarines, one of which they used to bomb Oregon -twice- and the French had one or two as well] is a bit unclear.The Axis was full of such grandiose plans late in the war. The Japanese had a somewhat similar plan to knock out the Panama canal using planes launched from submarines. However, they ran out of time and resources.

If even a few of the "New York Bombers" had bombed continental US targets, the US would undoubtedly have instituted costly air patrols, perhaps putting up observation and barrage balloons off the coast, and instituted naval surveillance for air attacks.

This could even have involved diversion of an aircraft carrier or two from the Pacific, picket lines of destroyers, and the like. Such an additional defense programme would have cost the US greatly and diverted resources from other pressing tasks [just as Operation Paukenschlag forced costly coastal convoys and coastal air patrols on the US for the last few years of the war..

It never happened, though, with the JU-390 project basically abandoned once the Allies captured the French airfields in August 1944. The planes based there were flown to Germany and destroyed.

An idle speculation is that Hitler [or others] could have flown this bomber somewhere far away as the Reich collapsed. It had the range to go almost anywhere, especially if modified for that express purpose. However, where would he have gone? What would he have done when he got there? There were no safe havens, nowhere to run.

The United States was in a unique position among all the powers involved in World War Two.

For the last time in its history, it was able to undertake military operations on a global scale relatively free of the fear of enemy reprisal. Its cities and factories were beyond the reach of any known enemy bomber. Moreover, much of its industrial capacity was located in its interior, far from the northeastern Atlantic States or the Pacific coast.

According to conventional wisdom that has been reiterated countless times in numerous standard histories of the war, there was absolutely nothing the United States had to fear from Nazi Germany with its "tactical mission-oriented Luftwaffe" or its puny Navy.

To this day, many Americans, even ones relatively familiar with the operational details of Word War Two,believe that Germany had no aircraft even capable of reaching the United States and returning to Europe, much less of carrying a heavy enough payload, or being available in sufficient numbers, to be of any military significance.

The Luftwaffe’s "Amerika Bomber"

7 January 2011

by Dr. Marshall Michel

52nd Fighter Wing historian

The "Amerika Bomber" project was an initiative of the World War II German Air Ministry to obtain a long-range strategic bomber for the Luftwaffe that would be capable of striking the continental U.S. from Germany — a range of about 5,800 kilometers.

The first public reference to the Amerika Bomber was on 8 July 1938, in a speech by the Luftwaffe’s commander in chief Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, and requests for designs were made to the major German aircraft manufacturers early in the war. Even though America was not in the war, it was clearly on the British side, and after the American-British Destroyers for Bases Agreement in September 1940, Hitler announced his desire to “deploy long-range bombers against American cities from the Portuguese Azores islands.”

A 33 page Amerika Bomber project plan was submitted to Göring on 27 April 1942, and specifically mentioned basing in the Azores, where Portuguese dictator Salazar had allowed German U-boats and navy ships to refuel, as a transit airfield. This would allow new, four engine bombers to reach the U.S. with a 5-ton payload. But from 1943 onward, he leased bases in the Azores to the British, allowing the Allies to provide aerial coverage in the middle of the Atlantic.

Though the Luftwaffe had asked German aircraft companies to eschew the development of heavy bombers in favor of tactical aircraft early in the war, Hitler’s desires meant four companies developed heavy bombers, the most promising being the German Junkers Ju 390, a simple development of the Junkers Ju 290 reconnaissance bombers already in service.

The Ju 390 prototypes were created by simply attaching an extra pair of inner-wing segments onto the wings of basic Ju 290 airframe to help accommodate two additional engines [three to a wing for a total of six BMW 801D 1,730 horsepower radial piston engines]. The fuselage was also lengthened by 8 feet, making the Ju 390 112 feet long with a wing span of 165 feet. It had a maximum take-off weight of 166,400 pounds and carried a 10 man crew.

The Junkers Ju 390 heavy bomber appeared when general German wartime philosophy was still centered around medium-class bomber aircraft. Full developmental resources were never really delegated to the Ju 390 project en mass and the entire program was slow.

With the second prototype, the plot thickened. According to some post war accounts, this Ju 390 made flight from the German base at Mont-de-Marsan, near Bordeaux, France, to Cape Town in early 1944.

But the most fascinating claim for the second prototype is that in April 1944 it made a 32-hour reconnaissance flight to within 12 miles off the coast of Long Island, N.Y.

But the most fascinating claim for the second prototype is that in April 1944 it made a 32-hour reconnaissance flight to within 12 miles off the coast of Long Island, N.Y.

There is considerable debate among aviation historians about whether this flight really took place.

A great circle round trip from France to St. Johns, Newfoundland, was quite possible, but the additional 2,380 miles to Long Island made the flight much more problematic, though certainly not impossible.

What would have been the aim of a small Luftwaffe raid on New York? It might have skewed American strategic priorities like the Doolittle Raid did for the Japanese, and it would have certainly forced a diversion of resources to defend the continental U.S.

But by this time in the war, U.S. military power was so overwhelming that such a diversion would hardly have been noticed.

In the event, anti-aircraft, Allied air strikes and the advance of the Soviet army forced the Germans to concentrate on defense, and the contracts for the 26 Ju 390s were canceled in June 1944. All work ceased in September of that year, but the question of the Ju-390’s mission to the U.S. remains one of the most interesting questions of the war.

The concept was raised as early as 1938, but advanced, cogent plans for such a long-range strategic bomber design did not begin to appear in Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring's offices until early 1942. Various proposals were put forward, including using the Amerika bomber to deliver proposed German nuclear weapons; these plans were all eventually abandoned as too expensive, too reliant on rapidly-diminishing materiel and production capacity, and/or technically unfeasible.

Background

In 1937, Willy Messerschmitt hoped to win a lucrative contract by showing Hitler a prototype of the Messerschmitt Me 264 that was being designed to reach North America from Europe.

"I completely lack the bombers capable of round-trip flights to New York with a 4.5-tonne bomb load. I would be extremely happy to possess such a bomber, which would at last stuff the mouth of arrogance across the sea".

Canadian historian Holger H. Herwig claims the plan started as a result of discussions by Hitler in November 1940 and May 1941 when he stated his need to "deploy long-range bombers against American cities from the Azores".

Due to their location, he thought the Portuguese Azores islands were Germany's "only possibility of carrying out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States".

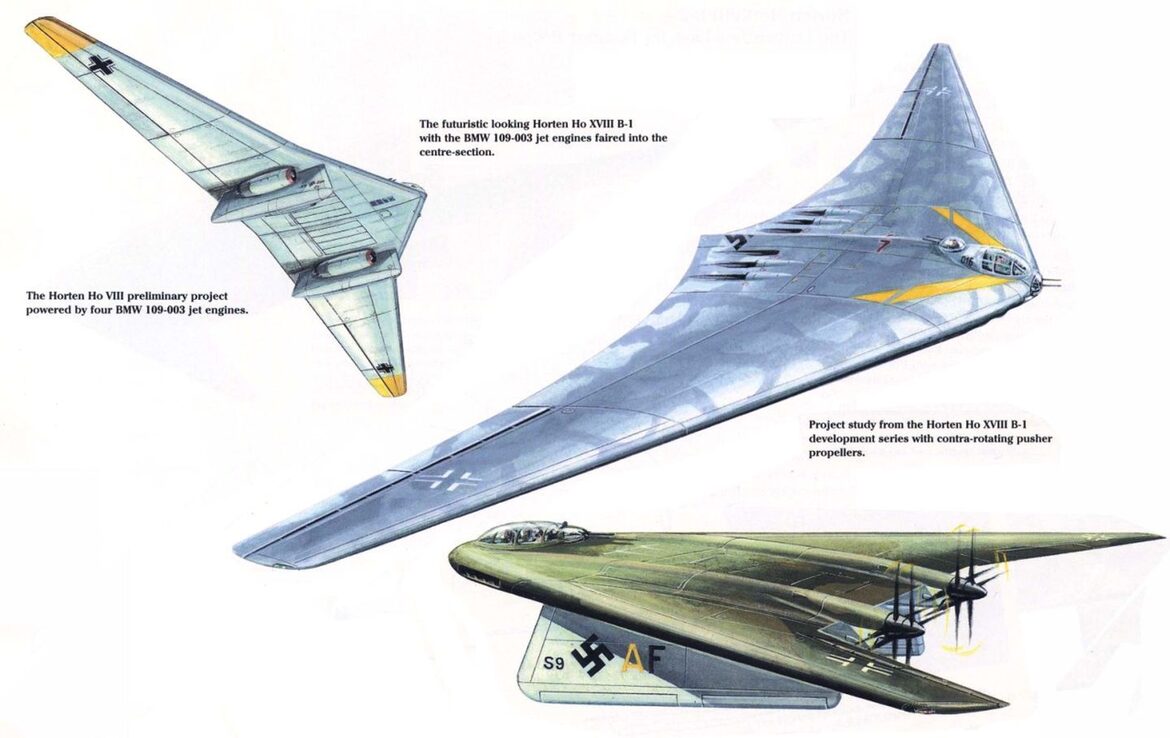

At the time, Portuguese Prime Minister Salazar had allowed German U-Boats and navy ships to refuel there, but from 1943 onwards, he leased bases in the Azores to the British, allowing the Allies to provide aerial coverage in the middle of the Atlantic.Requests for designs, at various stages during the war, were made to the major German aircraft manufacturers [Messerschmitt, Junkers, Focke-Wulf and the Horten Brothers] early in World War II, coinciding with the passage of the Destroyers for Bases Agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom in September 1940.

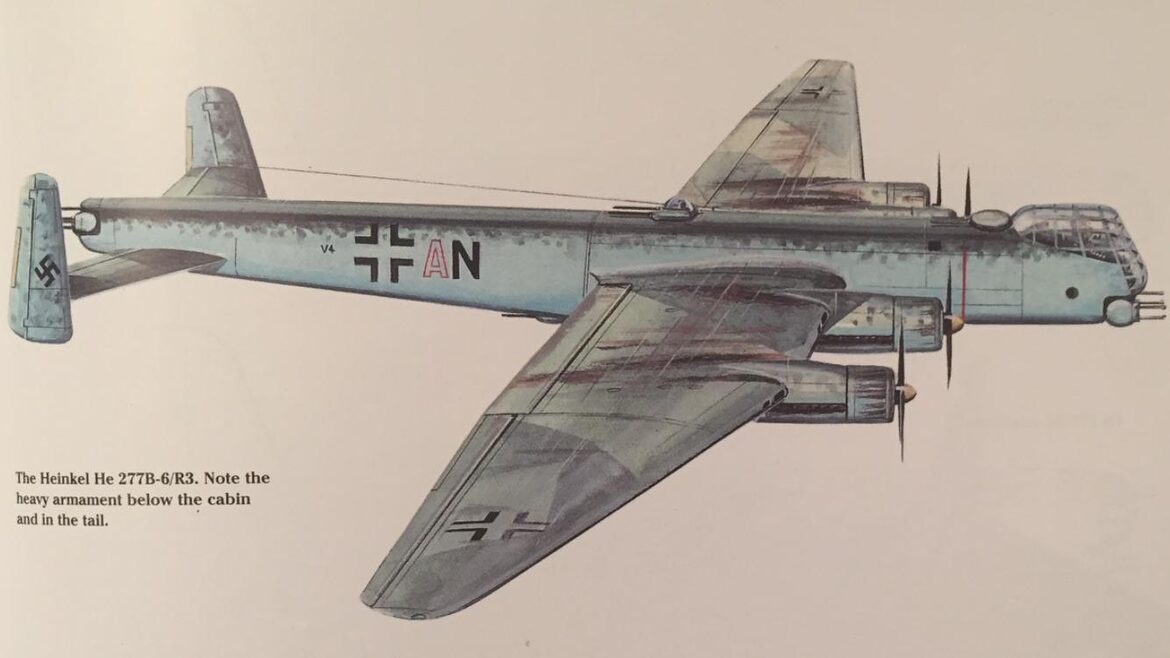

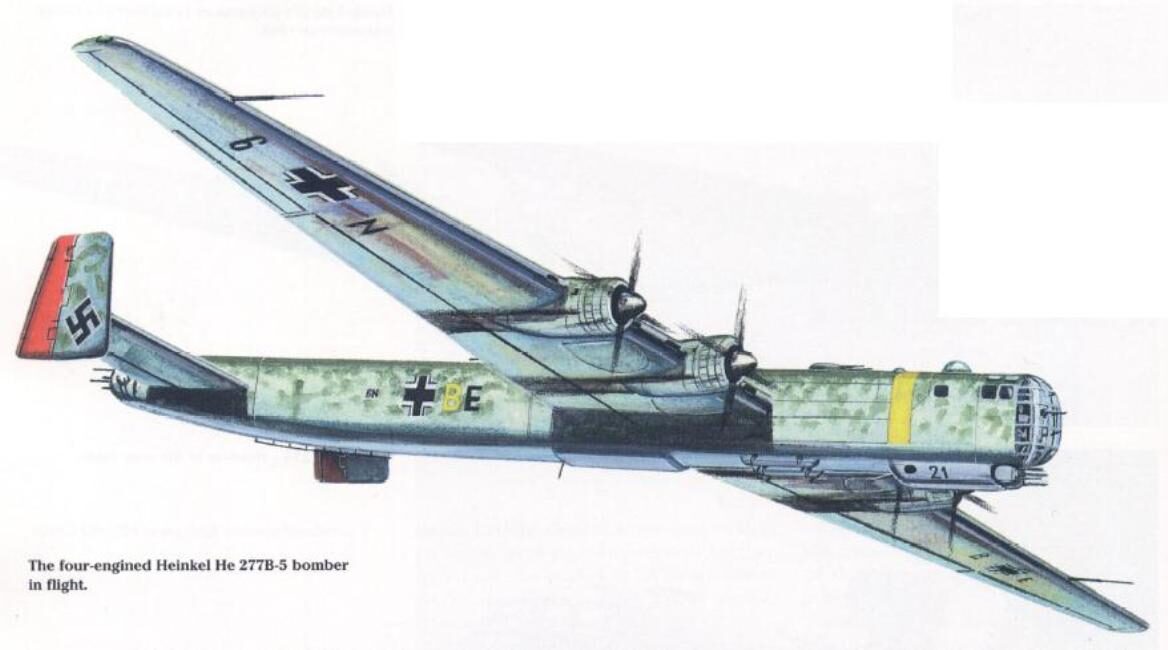

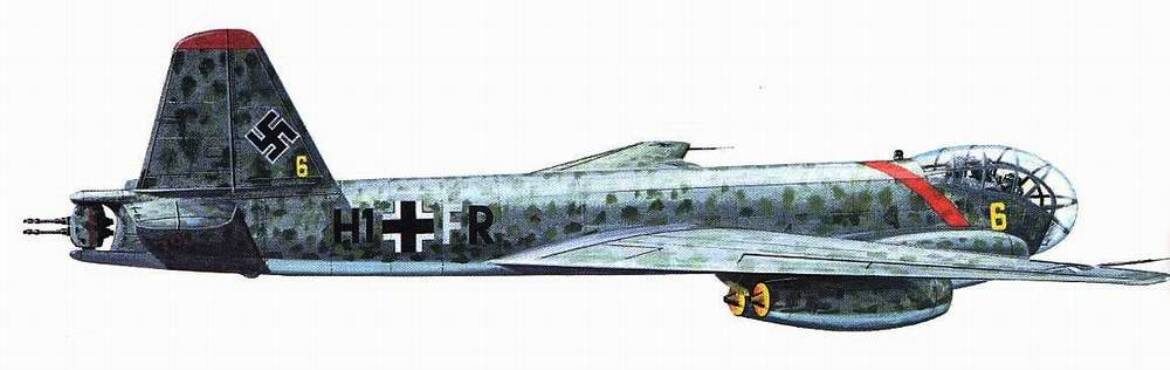

Heinkel's bid for the project had occurred sometime shortly after February 1943, by which time the RLM had issued the Heinkel firm the airframe type number 8-277 for what essentially became its entry.

The 33-page plan was discovered in Potsdam by Olaf Gröhler, a German historian. Ten copies of the plan were made, with six going to different Luftwaffe offices and four held in reserve. The plan specifically mentions using the Azores as a transit airfield to reach the United States.

If utilized, the Heinkel He 277, Junkers Ju 390, and the Messerschmitt Me 264 could reach American targets with a 3 tonne, 5 tonne, and 6.5 tonne payload respectively.

Although it is apparent that the plan itself deals only with an attack on American soil, it is possible the Nazis saw other interrelated strategic purposes for the Amerika bomber project.

According to military historian James P. Duffy, Hitler "saw in the Azores the ... possibility for carrying out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States ... [which in turn would] force it to build up a large anti-aircraft defense.". The anticipated result would have been to force the United States to use more of its antiaircraft capabilities—guns and fighter planes—for its own defense rather than for that of Great Britain, thereby allowing the Luftwaffe to attack the latter country with less resistance.

Von Gablenz gave his opinion on the Me 264, as it was in the second half of 1942, before von Gablenz's own commitments in the Battle of Stalingrad occurred: The Me 264 could not be usefully equipped for a true trans-Atlantic bomber mission from Europe, but it would be useful for a number of very long-range maritime patrol duties in co-operation with the Kriegsmarine's U-Boats off the US East Coast.

These included the following concepts:

A verified pair of the Ju 390 design were constructed before the program was abandoned.

After World War II, several authors claimed that the second Ju 390 actually made a transatlantic flight, coming within 20 km [12 mi] of the northeast U.S. coast in early 1944.

As both the Me 264 and He 277 were each intended to be four-engined bombers from their origins, the troubling situation of being unable to develop combat-reliable piston aviation engines of 1,500 kW [2,000 PS] and above output levels led to both designs being considered for six-engined upgrades, with Messerschmitt's paper project for a 47.5 meter wingspan "Me 264B" airframe upgrade to use six BMW 801E radials, and the Heinkel firm's 23 July 1943-dated request from the RLM to propose a 45-meter wingspan, six-engined variant of the still-unfinalized He 277 airframe design that could alternatively accommodate four of the troublesome, over-1,500 kW output apiece Junkers Jumo 222 24-cylinder six-bank liquid-cooled engines, or two additional BMW 801E radials beyond the original quartet of them that it was originally meant to use.

For the Do 217 it would have been a one-way trip. The aircraft would be ditched off the east coast, and its crew would be picked up by a waiting U-Boat.

When plans had advanced far enough, the lack of fuel and the loss of the base at Bordeaux prevented a test. The project was abandoned after the forced move to Istres increased the distance too much.

Missile Attack

In June of 1944, Germany deployed the world's first cruise missile to be used in combat: the V-1.

The V-1 was a small, pilotless plane launched from a long ramp and powered by a pulse-jet. The craft could carry its nearly 2,000 pound warhead a distance of 150 miles to a remote target. The Germans initially launched the V-1 from locations in France with most landing in the vicinity of the city of London.

The British found the V-1 difficult to stop. It flew too fast for most anti-aircraft guns to target and too fast for most fighter planes to overtake. Even if the craft was hit by gunfire, it wouldn't necessarily go down. Without a pilot or complex engine there were few points on the missile vulnerable to a single shot.

During the course of the war almost 23,000 people were killed by the V-1 and while defensive measures got better with time -faster fighters, better anti-aircraft guns- the threat to London was not completely removed until the Allied troops overran theV-1's launch points.

The introduction of the V-1 was followed by the V-2, the first ballistic missile ever used in war. The rocket stood 46 feet high and could carry a 2150 pound warhead 200 miles. Unlike the V-1, there were no defensive measures that could ever be devised against its threat. With an incoming velocity of nearly four times the speed of sound, nothing could catch it or stop it. It caused 2,745 deaths in London before its launch sites were overrun.

In the autumn of 1943 the Germans began to develop a plan that would have allowed them to attack American cities using the V-2 weapon.

The idea came from Dr. Bodo Lafferentz, one of the Third Reich's most brilliant engineers.

Lafferentz proposed building sealed canisters big enough to contain a V-2 and towing them behind a submarine to within 100 miles of the United States coast. It was estimated one submarine could tow up to three of these hundred-foot-long, torpedo-shaped canisters. Upon arrival the submarine would surface and remote controls would be used to flood the back end of the canisters to bring them from a horizontal position to a vertical one with just their tops clearing the surface of the ocean. The exposed end of the canisters would then be opened and technicians would enter the floating silos to prepare the V-2s for flight.

The Germans estimated that within thirty minutes the V-2s could be readied and launched. With the rockets on their way, the U-boat could then cut its connection to the canisters and flood them with water to sink them to the bottom. The submarine could then return to Germany while the three missiles continued on to plow into New York or some other American metropolis.

The project, given the name "Prufstand XII," was approved and construction of three prototype canisters was started early in 1945. The canisters were still under construction when the Soviets captured the shipyard where they were being built in April of 1945.

The attempt to strike at the United States by submarine might have easily been fulfilled by ignoring the V-2 and using the V-1.

The Americans tested this idea with their version of the V-1 , the Loon, in 1947.

A short ramp and hanger was added to the back of the submarine 'USS Cusk' and it was able to successfully launch the V-1 clone, track it by radar and guide it by radio to a target.

Surprisingly, the Germans never attempted to do this, though the head of Hitler's navy, Admiral Karl Admiral Dönitz, did attend a test firing of a V-1 in 1943. His presence there may have been related to this approach. It is clear that if the Germans had spent even a little time developing this idea there is no doubt they could have used such an arrangement to send a few V-1s into the heart of New York, or any other American east coast city.

Winged rockets

Many of these would not have been viable targets for conventional bombers of World War II, operating from bases in Europe.

Of these targets, primarily but not exclusively located in the eastern United States, 19 were located in the United States; one in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada [a possibly achievable target for a similar Japanese project] and one in Greenland.

Nearly all were companies that manufactured parts for aircraft, so the goal was likely to cripple U.S. aircraft production.

However, as historian James P. Duffy pointed out, Nazi Germany had no central authority for the development and construction of advanced weaponry, including new aircraft concepts and designs, as well as critical problems in developing high-powered aviation engines – that is, with output of over 1,500 kW [2,012 hp] each, which could operate reliably in combat conditions – that would have been required.

Hitler was often swayed to waste time, money and resources on new "miracle weapons" and other projects that were unlikely to be successful.

The Amerikabomber project was not one of the projects so favored.

In addition, Allied bombing became so intense during the middle of the war that it disrupted critical German supply chains, particularly fuel; in addition, ever-greater proportions of resources were reserved for home defense purposes. German scientists were forced more and more to compete for ever scarcer resources. Together, all of the above political and strategic constraints made construction of such an aircraft increasingly less likely.

There is a chance, however, that such attacks could have led to the war being lengthened. A successful attack on the United States would have greatly boosted the moral in Germany in the same way that the successful American air raid against Japan in 1942, led by Lieutenant Colonel James "Jimmy" Doolittle, raised American spirits.

Doolittle's 16 B-25 bombers did negligible damage to the Japanese war machine but caused the Japanese to recall some of their fighter units back to the home islands for defense and change important war strategies.

In the same way attacks on the U.S. east coast might have caused a public outcry forcing the U.S. military to devote more of their resources toward homeland defense. This, of course, would have tied up men and ships that were actually used to push the war in Europe quickly to a close. Such a change in plans might well have had the effect of lengthening the Third Reich's rule of terror.

If Hitler had wished to escape from Berlin in 1945 it was feasible

James P O'Donnell interviewed key characters from Hitler's Bunker immediately after the war. O'Donnell made a point of tracing 250 survivors of Hitler's Bunker after the war and interviewed 100 of the most important ones. He recounted in his book "The Berlin Bunker", published 1979, interviews with Reichsminister Albert Speer and Hitler's pilot Hans Baur about Speer's departure from Berlin.

On 29 April 1945 seven couriers left Hitler's Bunker [Führer Headquarters], SS Col Wilhelm Zander [Bormann's aide], Heinz Lorenz, Propaganda Ministry, Wehrmacht Maj Wili Johanmier [with Corp Hummerich], Maj Freytag von Löringhoven [Kreb's aide], Captain Gerhard Boldt [von Löringhoven's aide], LtCol Weiss [Burgdorf's aide] and Luftwaffe Col. von Below [with Corpl Heinz Matthiesing]. Zander and Lorenz had instructions to deliver Hitler's last will and testament to Dönitz at Plön to the north.

The standard, perhaps misleading account, is that these couriers all escaped 50 miles on foot through Russian lines along the Havel river to the Elbe, but astonishingly in his book O'Donnell said that the last of these seven couriers to leave, Col von Below, flew from Berlin on 29 April 1945.

Count von Below actually had orders from Hitler to fly south and have Göring arrested and the astonishing thing is that von Below actually did this. A number of Bv138 flying boats of KG200 are now known to have landed at Tiegel See northwest of Tiegel Airfield and to have evacuated senior Nazis from an island in that lake.

Hauptmann Ernst König in 2004 told British newspapers that he had been ordered on 1 May 1945 to prepare a Bv222 for an evacuation flight to Greenland with VIP Nazis from Berlin.

In his book O'Donnell cited Speer saying that Baur had serious plans to fly Hitler out on 23, 28 and 29 April 1945. He reported Baur being coy about the Ju-390 aircraft's ability to fly Hitler away from Berlin, but quoted Baur himself after the war saying "right up to the last day I could have flown the Führer anywhere in the world". Hitler however was determined to stay and commit suicide.

In his book O'Donnell quotes former Reichsminister Albert Speer whom he interviewed after the war saying that Baur was fascinated with Rechlin projects and especially the Ju-390.

Speer also said, "a Luftwaffe test pilot had flown a Ju-390 non-stop from Germany to Japan over the polar route. Baur would have known of this secret flight".

Disputed New York flight in 1944

There is a heavily disputed claim that in January 1944, a Ju-390 prototype made a trans-Atlantic flight from Mont-de-Marsan [near Bordeaux] to some 20 km [12 miles] off the coast of the United States and back. Critics claim FAGr.5 Fernaufklärungsgruppe 5] never flew such a flight.

Supporters say the only link between FAGr.5 and the New York flight is the common use of an airfield at Mont-de-Marsan and the veracity of the New York flight is neither proved nor disproved by a lack of unit records for such a flight. Indeed the flight may have had nothing whatsoever to do with FAGr.5 operations.

Whilst the Ju-390's 32-hour endurance would have certainly made such a crossing theoretically possible, there is a lack of evidence to support the claim. Aviation historian Horst Zöller claims the flight was recorded in Junkers company records.

Critics have also pointed to the vagueness of the aircraft's alleged position and even the date of what would have been a milestone flight. The best known [and maybe earliest publication] of the claim in English was in William Green's "Warplanes of the Third Reich" in 1970, where he wrote that the Ju 390 flew to "a point some 12 miles from the US coast, north of New York". Critics say the vagueness of detail and lack of corroborating evidence are hallmarks of an urban legend.

Critics believe that the aircraft would have had to overfly parts of the Massachusetts coast in order to fix their location, and point out the likelihood of the aircraft being spotted by observers and/or radar, which it was not. If New York State were meant, this would have put the aircraft closer to Boston. Critics ask why this city wasn't referred to for fixing the position of the claim. Finally, it is questioned how the aircrew would have been able to fix their position so accurately anyway.

Supporters argue that a Ju-390 crew could have obtained a highly accurate fix from public broadcast radio stations. Also that a Ju-390 would not have needed to overfly Massachusetts at all. They say there was no reason why New York City could not have been approached purely from the sea.

Supporters also note that the mission was designed to deliver a single bomb to New York and that such a bomb could only have been the atomic weapon under development. Japan and Germany at the time were using the "Harteck Process" of gaseous uranium centrifuges. Germany in 1944 was shipping both uranium ores and centrifuges to Japan by U-boat.

Supporters of the New York flight say of course the mission was kept secret so as not to tip off the US Government to provide better air defences. It was an ultra top secret test flight for the delivery of an atomic bomb.

Corroboration is gleaned from the so-called Silbervogel sub-orbital bomber designed to attack New York from space with only a single bomb. Only one type of bomb was worth all the time and expense involved. Supporters say a mission so secret would never have found its way into FAGr.5 logbooks.

Supporters note the top secret unit, II/KG200 also flew the Ju-390 as did Junkers company test pilots in Czechoslovakia.

Following the war, Hitler's armaments minister Albert Speer also recounted to author James P O'Donnell that a Ju-390 aircraft flown by Junkers test pilots flew a polar route to Japan in 1944.

Werrell himself later examined the available data regarding the Ju 390's range and concluded that although a great circle round trip from France to St. Johns, Newfoundland was possible, adding another 3,830 km [2,380 mi] for a round trip from St. Johns to Long Island made the flight "most unlikely".

Karl Kössler and Günter Ott, in their book "Die großen Dessauer: Junkers Ju 89, 90, 290, 390. Die Geschichte einer Flugzeugfamilie" [Great Dessauers...History of an Aircraft Family], also examined the claimed flight, and thoroughly debunked the flight north of New York. Most importantly, it was nowhere near France at the time when the flight was supposed to have taken place. A

ccording to Hans Pancherz' logbook, the Ju 390 V1 was brought to Prague on 26 November 1943. While there, it took part in a number of test flights, which continued until late March 1944.

Secondly, they also assert that the Ju 390 V1 prototype was unlikely to have been capable of taking off with the fuel load necessary for a flight of such duration due to strength concerns caused by its modified structure; it would have required a takeoff weight of 65 tonnes [72 tons], while the maximum takeoff weight during its trials had been 34 tonnes [38 tons].

According to Kössler and Ott, the Ju 390 V2 could not have made the US flight either, since they indicate that it was not completed before September/October 1944.

In his book, "The Bunker", author James P. O'Donnell mentions a flight to Japan. O'Donnell claimed that Albert Speer, in an early 1970s telephone interview, stated that there had been a secret Ju 390 flight to Japan "late in the war". The flight, by a Luftwaffe test pilot, had supposedly been non-stop via the polar route.

British journalist Tom Agoston interviewed the late Dr Wilhelm Voss from Hans Kammler's staff in Prague. Kammler from late 1944 was in charge of long distance transport aircraft.

Dr Voss claimed that a Ju-390 flew the polar route to Tokyo on 28 March 1945. According to Agoston aboard the plane were important spare parts, microfilm and possibly even key personnel. .

U-234's radio operator Wolfgang Hirschfeld in his book "Atlantik Farewell: Das Letzte U-boot" recalls plans to use an FW200 to Japan in 1945 to fly some of U-234's more urgent cargo. he went on to say the FW200 flight idea was abandoned because it could not satisfy Japan's demand that the flight not overfly Russia. Hirschfeld made no mention of the JU-390 flight but was hardly in a position to know every detail of what were secret flights.

What Hirschfeld does provide is an indication of a need for such a flight around March 1945 and an intention to operate such a flight about the time when Dr. Voss claimed it happened.

The Most Dangerous Photo-Recon Mission of World War II

By Jim Newsom U.S.A.

On 27 August 1943, a German Luftwaffe long-range photo reconnaissance bomber, a Junkers Ju-390 took off from its base in Norway and flew out across the Atlantic Ocean.

Among its four man crew was a brave and daring woman Anna Kreisling, the "White Wolf of the Luftwaffe": A nickname she had acquired because of her frost blonde hair and icy blue eyes.

Anna was one of the top pilots in Germany and even though she was only the co-pilot on this mission, her flying ability was crucial to its success.

The Ju-390 was twice the size of the B-29 Superfortress.

It was powered by six 1,500 hp BMW radial engines and it had a range of 18,000 miles without refueling.

The Ju-390 was 112 ft. 2 in length, wingspan 165 ft. while the B-29 had a length 99 ft. 0 in and wingspan 141 ft, which is proportionately about 15% bigger..

This hardly qualifies as "twice the size".

This was to be the longest photo-recon mission flown by an enemy airplane in World War II.

Nine hours later, the Junkers was over Canada and swinging south at an altitude of 22,000 feet.

In the next few hours, it would photograph the heavy industrial plants in Michigan that were vital to the United States.

By noon on August 28th the gigantic six engined bomber was over New York City where it finally was spotted by the US Army Air Corp. but by then it was too late.

The Junkers disappeared into the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean, fourteen hours later, Anna would bring the huge bomber in to land at a Luftwaffe base outside of Paris.

Thoughts of this mission came to mind as I sat across the table from Anna Kreisling at a recent Octoberfest in Los Angeles.

She is still quite beautiful with her icy blonde hair tied-back in a pony-tail and her radiant blue eyes, which have seen events in human history only a few of us could ever imagine.

She had flown Ju-52 Trimotors into the streets of Stalingrad when it had been surrounded by the Red Army.

Only forty-seven Ju 290s were built, in transport and maritime patrol/bomber versions.

But what if the Third Reich had invested in four-engine heavies on the same vast scale as the British and Americans?

If a thousand Ju 290s had been available for the 24 November 1942-31 January 1943 German airlift to Stalingrad –in which 266 smaller and less capable Ju 52 tri-motors were lost in battle– the rash promise of a successful supply effort made by Hermann Göring, might have been fulfilled.

The outcome of one of history’s largest battles might have been different.

The Ju 290 was a tailwheel-equipped aircraft similar in configuration to the U.S. B-17 Flying Fortress or the British Handley-Page Halifax – but about 20 percent larger than either.

Long after 1936, when the Reich abandoned an ambitious project for a "Ural bomber" capable of striking Soviet targets to the east beyond the Ural mountain range, the Ju 290 was developed from the Ju 90 airliner and made its first flight on 16 July 1942.

The prototype Ju 290 V1 and the first eight Ju 290 A-1s were unarmed transports and were rushed into service, but only one was available to participate in the Stalingrad airlift.

Many times her plane had been riddled with bullets so badly that she landed with only one engine running while the other two were on fire.

In 1945 she was assigned to fly the jet fighters that Germany was producing.

One of these jet fighters was the Horten IX flying wing. It was powered by two Jumo turbo-jet engines, which enabled it to fly at 600 mph.

It was armed with two 30mm cannon and air to air missiles.

Anna never scored any victories in the Horten.

While taxiing in the snow an American Sherman tank crew captured her after she had turned off the engine and pulling off her flight helmet they thought she was a movie star.

For the next six months she poured coffee for the US Army and did not spend one night in a POW camp. Everyone thought she was part of Bob Hope’s USO show.

If you look in books they will say that only two Ju-390s were built, when in fact there were around 11 built. Also they were used in Odessa, Russia to fly to Japanese held fields in China.

Very secret jet engines and technology was traded for raw materials. At Area 51 in Nevada the United States Air Force it is rumored has a Junkers Ju-390 it captured during Operation Paperclip toward the end of World War II.

P.S. An article in "Air Progress magazine" in the Nov/Dec issue 1965 also talked about the Junkers Ju-390 over-flying Michigan and New York.

This was held top secret throughout World War II and the Cold War.

Notes: