- MAIN INDEX: Adolf Hitler Death and Survival: Legend, Myth and Reality

- The Final Years of WWII

- "Operation Paperclip" and Underground Bases

- How the Nazis planned a Fourth Reich...in the EU

- The Great Patents Heist in Germany after WWII

- Did Hitler Have Only One Testicle?

- Argentina

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 1

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 2

- Nazi Secret Weapons and The Cold War Allied Legend - Part 3

- The "Race" to the Moon"

- Wunderwaffen

- Hans Kammler

- Junkers Ju 390

- Mysterious German Bombs Aircrafts, and Carriers

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 1

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 2

- German Atom Bomb and WMDs - Part 3

- Die Glocke

- "Sweats"

- Hitler's Vergeltungswaffen

- The Coming of the 4th Reich

- “We can still lose this war” - General George Patton

- German "Super Science"

- Amerika Bombers

Revealed: The secret report that shows how the Nazis planned a Fourth Reich...in the EU

By Adam Lebor

MailOnline

9 May 2009

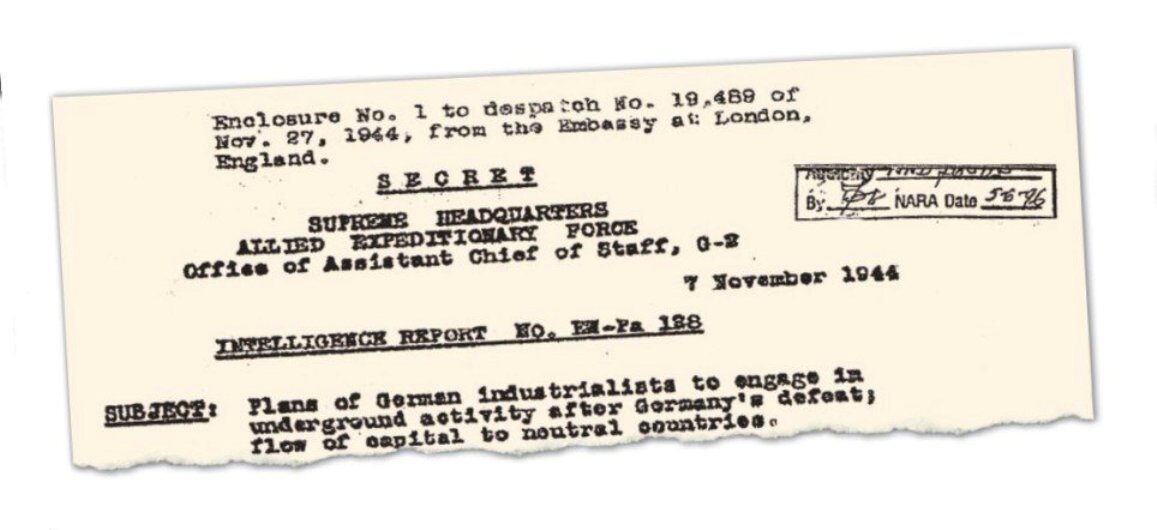

The paper is aged and fragile, the typewritten letters slowly fading. But US Military Intelligence report EW-Pa 128 is as chilling now as the day it was written in November 1944.

The document, also known as the 'Red House Report', is a detailed account of a secret meeting at the Maison Rouge Hotel in Strasbourg on 10 August 1944.

The meeting was organized by Martin Bormann, although he did not personally attend the confererence.

He was represented by Dr. Friedrich Scheid, a lieutenant-general in the Waffen-SS and also a director of the industrial company Hermsdorf & Schomburg.

The three-page, closely typed report, marked "Secret"', copied to British officials, was sent by air pouch to Cordell Hull, the US Secretary of State.

It detailed how the industrialists were to work with the Nazi Party to rebuild Germany's economy by sending money through Switzerland.

They would set up a network of secret front companies abroad.

They would wait until conditions were right.

And then they would take over Germany again.

The industrialists included representatives of Volkswagen, Krupp and Messerschmitt.

Officials from the Navy and Ministry of Armaments were also at the meeting.

With incredible foresight, they decided together that the Fourth German Reich, unlike its predecessor, would be an economic rather than a military empire.

The Red House Report, unearthed from US Intelligence files, was the inspiration for my thriller "The Budapest Protocol".

But as I researched and wrote the novel, I realised that some of the Red House Report had become fact.

Nazi Germany did export massive amounts of capital through neutral countries. German businesses did set up a network of front companies abroad. The German economy did soon recover after 1945.

The Third Reich was defeated militarily, but powerful Nazi-era bankers, industrialists and civil servants, reborn as democrats, soon prospered in the new West Germany. There they worked for a new cause: European economic and political integration.

Is it possible that the Fourth Reich those Nazi industrialists foresaw has, in some part at least, come to pass?

The Red House Report was written by a French spy who was at the meeting in Strasbourg in 1944 - and it paints an extraordinary picture.

The industrialists gathered at the Maison Rouge Hotel waited expectantly as SS Obergruppenführer Dr Scheid began the meeting. Scheid held one of the highest ranks in the SS, equivalent to Lieutenant General. He cut an imposing figure in his tailored grey-green uniform and high, peaked cap with silver braiding.

Obergruppenführer Dr. Johann Friedrich Scheid - Director of Hermsdorf-Schönburg GMBH. Had Honorary SS Rank.

In August 1944 he presided over a secret meeting with German industrialists to using assets to rebuild Germany in the post- war period.

Guards were posted outside and the room had been searched for microphones.

In 1942 Dr. Scheid held an important position in Albert Speer’s Ministry of Armaments and Munitions, and at the end of 1942, I.G. Farben’s Dr. Walter Schieber, Chief of the Armaments Delivery Office, put him in charge of the Bureau of “Industrial Independence" in which position he had far-reaching responsibility for the Nazi arms industry.

Walter Schieber was an SS Brigadeführer in Nazi Germany, who during the Second World War served as head of the Armaments Supply Office under Albert Speer.

In 1943, Adolf Hitler awarded Schieber the War Merit Cross.

After the war, the US government became interested in hiring Schieber for scientific research purposes.

A 1947 U.S. Air Force memo stated that "Dr. Schieber's talents are of so important a nature to the U.S. that they go far to override any consideration of his political background".

In the end, Schieber's profile meant it was not possible to bring him to America, but he was employed by the US for ten years in chemical warfare research in West Germany

As reported in an article entitled 'General Eisenhower: Interesting Document', in "Junge Welt", Dr. Scheid fled from Berlin in April 1945 and was interned by the Soviet occupation forces from June 1945 until 31 December 1945. He was subsequently named the German director of the Board of the Soviet Joint Stock Company [SAG]. He died in 1949.

There was a sharp intake of breath as he began to speak. German industry must realise that the war cannot be won, he declared. 'It must take steps in preparation for a post-war commercial campaign.' Such defeatist talk was treasonous - enough to earn a visit to the Gestapo's cellars, followed by a one-way trip to a concentration camp.

But Scheid had been given special licence to speak the truth – the future of the Reich was at stake. He ordered the industrialists to 'make contacts and alliances with foreign firms, but this must be done individually and without attracting any suspicion'.

The industrialists were to borrow substantial sums from foreign countries after the war.

They were especially to exploit the finances of those German firms that had already been used as fronts for economic penetration abroad, said Scheid, citing the American partners of the steel giant Krupp as well as Zeiss, Leica and the Hamburg-America Line shipping company.

But as most of the industrialists left the meeting, a handful were beckoned into another smaller gathering, presided over by Dr Bosse of the Armaments Ministry. There were secrets to be shared with the elite of the elite.

Bosse explained how, even though the Nazi Party had informed the industrialists that the war was lost, resistance against the Allies would continue until a guarantee of German unity could be obtained. He then laid out the secret three-stage strategy for the Fourth Reich.

In stage one, the industrialists were to 'prepare themselves to finance the Nazi Party, which would be forced to go underground as 'Maquis', using the term for the French resistance.

Stage two would see the government allocating large sums to German industrialists to establish a 'secure post-war foundation in foreign countries', while 'existing financial reserves must be placed at the disposal of the party so that a strong German empire can be created after the defeat'.

In stage three, German businesses would set up a 'sleeper' network of agents abroad through front companies, which were to be covers for military research and intelligence, until the Nazis returned to power.

'The existence of these is to be known only by very few people in each industry and by chiefs of the Nazi Party,' Bosse announced.

'Each office will have a liaison agent with the party. As soon as the party becomes strong enough to re-establish its control over Germany, the industrialists will be paid for their effort and co-operation by concessions and orders.'

The exported funds were to be channelled through two banks in Zürich, or via agencies in Switzerland which bought property in Switzerland for German concerns, for a five per cent commission.

The Nazis had been covertly sending funds through neutral countries for years.

Swiss banks, in particular the Swiss National Bank, accepted gold looted from the treasuries of Nazi-occupied countries. They accepted assets and property titles taken from Jewish businessmen in Germany and occupied countries, and supplied the foreign currency that the Nazis needed to buy vital war materials.

Swiss economic collaboration with the Nazis had been closely monitored by Allied intelligence.

The Red House Report's author notes: 'Previously, exports of capital by German industrialists to neutral countries had to be accomplished rather surreptitiously and by means of special influence.

'Now the Nazi Party stands behind the industrialists and urges them to save themselves by getting funds outside Germany and at the same time advance the party's plans for its post-war operations'.

The order to export foreign capital was technically illegal in Nazi Germany, but by the summer of 1944 the law did not matter.

More than two months after D-Day, the Nazis were being squeezed by the Allies from the west and the Soviets from the east. Hitler had been badly wounded in an assassination attempt. The Nazi leadership was nervous, fractious and quarrelling.

During the war years the SS had built up a gigantic economic empire, based on plunder and murder, and they planned to keep it.

A meeting such as that at the Maison Rouge would need the protection of the SS, according to Dr Adam Tooze of Cambridge University, author of "Wages of Destruction: The Making And Breaking Of The Nazi Economy".

He says: "By 1944 any discussion of post-war planning was banned. It was extremely dangerous to do that in public. But the SS was thinking in the long-term. If you are trying to establish a workable coalition after the war, the only safe place to do it is under the auspices of the apparatus of terror".

Shrewd SS leaders such as Otto Ohlendorf were already thinking ahead.

As commander of Einsatzgruppe D, which operated on the Eastern Front between 1941 and 1942, Ohlendorf was responsible for the murder of 90,000 men, women and children.

A highly educated, intelligent lawyer and economist, Ohlendorf showed great concern for the psychological welfare of his extermination squad's gunmen: he ordered that several of them should fire simultaneously at their victims, so as to avoid any feelings of personal responsibility.

By the winter of 1943 he was transferred to the Ministry of Economics. Ohlendorf's ostensible job was focusing on export trade, but his real priority was preserving the SS's massive pan-European economic empire after Germany's defeat.

Ohlendorf, who was later hanged at Nuremberg, took particular interest in the work of a German economist called Ludwig Erhard. Erhard had written a lengthy manuscript on the transition to a post-war economy after Germany's defeat. This was dangerous, especially as his name had been mentioned in connection with resistance groups.

But Ohlendorf, who was also chief of the SD, the Nazi domestic security service, protected Erhard as he agreed with his views on stabilising the post-war German economy. Ohlendorf himself was protected by Heinrich Himmler, the chief of the SS.

Ohlendorf and Erhard feared a bout of hyper-inflation, such as the one that had destroyed the German economy in the Twenties. Such a catastrophe would render the SS's economic empire almost worthless.

The two men agreed that the post-war priority was rapid monetary stabilisation through a stable currency unit, but they realised this would have to be enforced by a friendly occupying power, as no post-war German state would have enough legitimacy to introduce a currency that would have any value.

That unit would become the Deutschmark, which was introduced in 1948. It was an astonishing success and it kick-started the German economy. With a stable currency, Germany was once again an attractive trading partner.

The German industrial conglomerates could rapidly rebuild their economic empires across Europe.

War had been extraordinarily profitable for the German economy. By 1948 - despite six years of conflict, Allied bombing and post-war reparations payments - the capital stock of assets such as equipment and buildings was larger than in 1936, thanks mainly to the armaments boom.

Erhard pondered how German industry could expand its reach across the shattered European continent. The answer was through supranationalism - the voluntary surrender of national sovereignty to an international body.

Germany and France were the drivers behind the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the precursor to the European Union. The ECSC was the first supranational organisation, established in April 1951 by six European states. It created a common market for coal and steel which it regulated. This set a vital precedent for the steady erosion of national sovereignty, a process that continues today.

But before the common market could be set up, the Nazi industrialists had to be pardoned, and Nazi bankers and officials reintegrated. In 1957, John J. McCloy, the American High Commissioner for Germany, issued an amnesty for industrialists convicted of war crimes.

The two most powerful Nazi industrialists, Alfried Krupp of Krupp Industries and Friedrich Flick, whose Flick Group eventually owned a 40 per cent stake in Daimler-Benz, were released from prison after serving barely three years.

Krupp and Flick had been central figures in the Nazi economy. Their companies used slave labourers like cattle, to be worked to death.

The Krupp company soon became one of Europe's leading industrial combines.

The Flick Group also quickly built up a new pan-European business empire. Friedrich Flick remained unrepentant about his wartime record and refused to pay a single Deutschmark in compensation until his death in July 1972 at the age of 90, when he left a fortune of more than $1billion, the equivalent of £400million at the time.

'For many leading industrial figures close to the Nazi regime, Europe became a cover for pursuing German national interests after the defeat of Hitler,' says historian Dr Michael Pinto-Duschinsky, an adviser to Jewish former slave labourers.

'The continuity of the economy of Germany and the economies of post-war Europe is striking. Some of the leading figures in the Nazi economy became leading builders of the European Union'.

Numerous household names had exploited slave and forced labourers including BMW, Siemens and Volkswagen, which produced munitions and the V1 rocket.

Slave labour was an integral part of the Nazi war machine. Many concentration camps were attached to dedicated factories where company officials worked hand-in-hand with the SS officers overseeing the camps.

Like Krupp and Flick, Hermann Abs, post-war Germany's most powerful banker, had prospered in the Third Reich. Dapper, elegant and diplomatic, Abs joined the board of Deutsche Bank, Germany's biggest bank, in 1937. As the Nazi empire expanded, Deutsche Bank enthusiastically 'Aryanised' Austrian and Czechoslovak banks that were owned by Jews.

By 1942, Abs held 40 directorships, a quarter of which were in countries occupied by the Nazis. Many of these Aryanised companies used slave labour and by 1943 Deutsche Bank's wealth had quadrupled.

Abs also sat on the supervisory board of I.G. Farben, as Deutsche Bank's representative. I.G. Farben was one of Nazi Germany's most powerful companies, formed out of a union of BASF, Bayer, Hoechst and subsidiaries in the Twenties.

It was so deeply entwined with the SS and the Nazis that it ran its own slave labour camp at Auschwitz, known as Auschwitz III, where tens of thousands of Jews and other prisoners died producing artificial rubber.

Under the direction of Dr Herman Josef Abs [who never became a Nazi] the Deutsche Bank was responsible for financing the slave labour used by business giants such as Siemens, BMW, Volkswagen, I.G. Farben, Daimler Benz and others.

The banks wealth quadrupled during the twelve years of Hitler's rule. Arrested by the British after the war for war crimes, he was quietly released after the intervention of the Bank of England to help restore the German banking industry in the British zone.

This caused much dissension between the British and the Americans who wanted the German Economy crushed.

When they could work no longer, or were "verbraucht" [used up] in the Nazis' chilling term, they were moved to Birkenau. There they were gassed using Zyklon B, the patent for which was owned by I.G. Farben.

But like all good businessmen, I.G. Farben's bosses hedged their bets.

During the war the company had financed Ludwig Erhard's research. After the war, 24 I.G. Farben executives were indicted for war crimes over Auschwitz III - but only twelve of the 24 were found guilty and sentenced to prison terms ranging from one-and-a-half to eight years. I.G. Farben got away with mass murder.

Abs was one of the most important figures in Germany's post-war reconstruction. It was largely thanks to him that, just as the Red House Report exhorted, a "strong German empire" was indeed rebuilt, one which formed the basis of today's European Union.

Abs was put in charge of allocating Marshall Aid - reconstruction funds - to German industry. By 1948 he was effectively managing Germany's economic recovery.

Crucially, Abs was also a member of the European League for Economic Co-operation, an elite intellectual pressure group set up in 1946. The league was dedicated to the establishment of a common market, the precursor of the European Union.

Its members included industrialists and financiers and it developed policies that are strikingly familiar today - on monetary integration and common transport, energy and welfare systems.

When Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of West Germany, took power in 1949, Abs was his most important financial adviser.

Behind the scenes Abs was working hard for Deutsche Bank to be allowed to reconstitute itself after decentralisation. In 1957 he succeeded and he returned to his former employer.

That same year the six members of the ECSC signed the Treaty of Rome, which set up the European Economic Community. The treaty further liberalised trade and established increasingly powerful supranational institutions including the European Parliament and European Commission.

Like Abs, Ludwig Erhard flourished in post-war Germany. Adenauer made Erhard Germany's first post-war economics minister. In 1963 Erhard succeeded Adenauer as Chancellor for three years.

But the German economic miracle – so vital to the idea of a new Europe - was built on mass murder. The number of slave and forced labourers who died while employed by German companies in the Nazi era was 2,700,000.

Some sporadic compensation payments were made but German industry agreed a conclusive, global settlement only in 2000, with a £3billion compensation fund. There was no admission of legal liability and the individual compensation was paltry.

A slave labourer would receive 15,000 Deutschmarks [about £5,000], a forced labourer 5,000 [about £1,600]. Any claimant accepting the deal had to undertake not to launch any further legal action.

To put this sum of money into perspective, in 2001 Volkswagen alone made profits of £1.8billion.

Next month, 27 European Union member states vote in the biggest transnational election in history. Europe now enjoys peace and stability. Germany is a democracy, once again home to a substantial Jewish community. The Holocaust is seared into national memory.

But the Red House Report is a bridge from a sunny present to a dark past. Josef Göbbels, Hitler's propaganda chief, once said: 'In 50 years' time nobody will think of nation states.'

For now, the nation state endures. But these three typewritten pages are a reminder that today's drive towards a European federal state is inexorably tangled up with the plans of the SS and German industrialists for a Fourth Reich - an economic rather than military imperium.

--"The Budapest Protocol", Adam LeBor's thriller inspired by the Red House Report, is published by Reportage Press.

The US Military Intelligence report EW-Pa 128, otherwise know as the "Red House Report", is a bit of a mystery. Because of its explosive content it is widely distributed in the conspiracy community, but there is no single solid reference to be found.

British author and journalist Adam LeBor cites the report as inspiration for his first novel "The Budapest Protocol" [2009] in the "Daily Mail", but the latter can hardly be cited as reputable source. The report is also mentioned in Michael Bar-Zohar's book "The Avengers" and the 2008 documentary "Le système Octogon" by Jean-Michel Meurice in collaboration with Fabrizio Calvi and Frank Garbely, but publication details are not mentioned either. Finally it is alluded to by Martin Lorenz-Meyer in "Safehaven: The Allied Pursuit of Nazi Assets Abroad" [University of Missouri Press, 2007], again without reference or footnote.

SOLID REFERENCES:

There were meetings such as one between delegates from the NS Armaments Ministry, led by Albert Speer, and the NS Economics Ministry as well as representatives of armaments companies from the Rhine/Ruhr regions and one chaired by top-level SS officers.

Chaired by Wehrwirtschaftsführer Dr. Friedrich Scheid, this took place on 10 August 1944 in the hotel "Rotes Haus" in Strasbourg – in the period after the Allied Normandy landings in June and when the fall of Paris could be predicted, as well as the defeat of the NS regime itself.

This document, which apparently has not yet made an impact on German history-writing, but which was referenced in the minutes of a meeting of the Subcommittee on War Mobilization at the US Senate on 25 June 1945, led by Senator Harley M. Kilgore; was officially declassified by the US authorities in 2000.

Research has uncovered basic designs for “Nazi post-war planning” but little research has been conducted on the post-1945 implementation of that planning.

It is nonetheless known that after the end of the war, a large number of severely "tainted" high-level functionaries of the NS regime managed to escape to South America via routes known as the "Ratlines", with help from the Vatican and Red Cross.

Additionally, many companies who had worked closely with the NS regime managed to transfer large sums of money and technological expertise into “neutral foreign countries”, from where it could be reintroduced into the German economy some years later.

The extent of the capital and technology transfer from the doomed NS regime to neutral countries [particularly Sweden, Switzerland, Argentina, Brazil and other South American countries] is still insufficiently researched; US estimates, however, speak of billions of dollars

On Thursday, 21 June 1945, the "The Neosho Daily News" in Missouri, published the following report:

GERMAN PLAN FOR WORLD WAR III REVEALED

Senate Committee to Begin Hearings On Documents Tomorrow.

[By the United Press]

From within Germany and from the nation's capital this morning came two stories which add up to the same conclusion — the leaders of defeated Germany are planning World War III.

Senator Harley Kilgore has just released a report which charges flatly that German industrialists planning to re-arm their country already have put the machinery into action. And United Press correspondent Jack Fleisher cables from Berchtesgaden that the great German industries are going underground.

Documents Captured

Senator Kilgore has just returned from a tour of Europe. He brought home with him documents found in the defeated country. One of them —hither labelled a top secret — has been made public. It was drawn up at a meeting of German industrialists at Strasbourg on 10 August 1944 —almost a year ago.

And that document gives step by step the plans of leading industrialists to wash their hands of the Nazi party, strengthen their contacts with foreign firms, and to start producing for another war, disguising their production under the name of "non-military research".

According to the West Virginia Senator's report a certain Doctor Scheid presided over the meeting which was attended by top men from such German industries as the Krupp works, the Messerschmitt factoriee,,and representatives of the German naval ministry and the ministry of armament. Incidentally, a report just in says British military authorities are holding munitions king Alfred Krupp in a secret prison for possible trial as a war criminal.

Allies Would Finance

Scheid is quoted as telling the group that German industry must borrow foreign money —as it did after World War I—to create a strong German empire. Large factories were told to open small research bureaus which would receive drawings of new money says the Nazi document. "These should be established either, in large cities, where they can be most successfully hidden, or in little villages near sources of hydro-electric power".

The report next blandly orders — "The existence of the secret factories is to be known only by a few people in each industry and by chiefs of the Nazi party. Each office will have a liaison with the party". And it adds— "As soon as the party becomes strong enough to re-establish its control over Germany, the industrialists will be paid for their efforts by concessions and orders".

Other Hidden Proof

No sooner was Senator Kilgore's report on the wire than "United Press" correspondent Jack Fleisher cabled that American troops are finding key parts of factories and research data scattered systematically in pre-arranged hiding places all over Germany.

Fleisher says the industrialists had hoped to climax their defeat by wrecking the industrial economy of Germany, with the long-term hope of making a comeback under cover of Allied confusion. But a split in the German ranks and the quick action of Allied troops has kept the plan from going into full swing.

First — the main industrialists and the Nazi party hid the important parts of factories to be destroyed from the Army. Second - all material associated with companies had disappeared.

The EU was Hitler's idea

and it proves Germany won the Second World War, claims new book

By Owen Bennett - Political Reporter

Daily Express

17 April 2014

The EU: The Truth About The Fourth Reich: How Hitler Won The Second World War" argues the single currency, the free market and even the phrase "United States of Europe" were all dreamt up by high ranking Nazis, including the Führer himself.

It also claims the only country which benefits from the EU is Germany - just as Hitler planned.

A spokesperson for the Liberal Democrats -which its leader Nick Clegg describes as the "party of in" when it comes to the EU- dismissed the authors of the book as "peddling outlandish myths".

The book, co-written by Daniel J Beddowes and Falvio Cipollini, says:

"What is the EU for? Who really benefits? And the answer is of course Germany.

"It is no coincidence that just about every country in the European Union is getting poorer while Germany continues to get richer and richer.

"We may think we won the Second World War. But we lost. It is no surprise that we are all living in the Fourth Reich.

"Knowingly or not those who support and defend the European Union are supporting the Nazi legacy".

Under a chapter heading 'The EU was inspired an designed by Nazis', the authors claim:

"Hitler, was the man who gave bones to the dreams first expressed by Charlemagne and Napoleon.

But the finishing touches to the EU as we know it were put in place during World War II by a man called Walther Funk, who was President of the Reichsbank and a director of the Bank for International Settlements.

"It was Funk who predicted the coming of European economic unity.

Funk was also Adolf Hitler's economics minister and his key economics advisor".

It continues: "The Nazis wanted to get rid of the clutter of small nations which made up Europe and their plan was quite simple. The EU was Hitler's dream".

The EU was designed by Benito Mussolini, Hitler and Walther Funk [Hitler's economics advisor]. Other senior Nazis helped plan the EU. This book contains the details of precisely how and when they did it. Hitler invented the phrase United States of Europe. Hermann Göring devised the name European Economic Community. The Euro was Funk's idea. And Reinhard Heydrich, one of the main architects of the Holocaust, published an early version of The Treaty of Rome.

The book argues it is no coincidence that the EU is so close to Hitler's plan for post-war Europe.

According to the authors:

"In 1945, Hitler's Masterplan was captured by the Allies. The Plan included details of his scheme to create an economic integration of Europe and to found a European Union on a federal basis.

"The Nazi plan for a federal Europe was based on Lenin's belief that 'federation is a transitional form towards complete union of all nations'.

"It is impossible to find a difference between Hitler's plan for a new United States of Europe, dominated by Germany, and the European Union we have today".

The book also claims Conservative Prime Minister Ted Heath -"a self-confessed liar and a traitor"- was paid £35,000 to take Britain into the European Economic Community in 1973 and Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Göbbels would be proud of the BBC's support of the EU.

The final part of the book lists "73 things you ought to know about the EU [Facts the BBC forgot to tell you]".

In amongst concerns about immigration and the Common Agricultural Policy, the authors argue "The EU is making DIY illegal", "EU law forces pig owners to apply for walking licences" and "The EU wants to control the music you listen to".

It also claims:

"The EU has forced us to use light bulbs which are more dangerous and more expensive than the old ones.

"The first problem with the new EU light-bulbs is that the light produced by them is so poor that people have difficulty seeing where they are going - let alone being able to see well enough to read or work".

According to the book, European Commission vice-president Viviane Reding crystallised "Hitler's dream, Hitler's words" earlier this year when she "called for a 'true political union' and a campaign for the European Union to become a 'United States of Europe'.

A Liberal Democrat spokesperson said:

"People have been peddling outlandish myths about the EU for decades and this book is an example of that. Some of the suggestions made are completely ludicrous. Winston Churchill called for a “United States of Europe” and I doubt the author would call him a Nazi.

“The Liberal Democrats want Britain to stay in the EU because we are fighting for a stronger economy – fighting to defend millions of British jobs which are linked to our trade with the EU.

"Being in Europe gives us more strength when negotiating trade deals with global players on the world stage".

It is not the first time the EU has been described as a German plot to take over Europe.

In 1990, Cabinet Minister Nicholas Ridley -a close ally of Margaret Thatcher- was forced to resign after he described proposed Economic and Monetary Union as "a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe" and said that giving up sovereignty to the European Union was as bad as giving it up to Hitler.

US Military Intelligence Report EW-Pa 128, 27 November 1944 was published in:

Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee of Military Affairs. United States Senate. Seventy-Ninth Congress. First Session. Pursuant to Senate Resolution 107 [78th Congress] and Senate Resolution 146 [79th Congress], Part. 2, 25 June 1945.

Its contents are also reproduced in:

- Henry Morgenthau Jr., "Germany Is Our Problem". New York, 1945; a German translation can be found in: Förster/Gröehler, "Der zweite Weltkrieg. Dokumente, Berlin [Ost]", 1972; a facsimilie is reprinted in: Gaby Weber, "Daimler-Benz und die Argentinien-Connection. Von Rattenlinien und Nazigeldern", Berlin, 2004;

- A consideration of the document which critically examines the sources can be found in Dietrich Eichholtz, "Das Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion und die Straßburger Tagung vom 10. August 1944", in: Bulletin des Arbeitskreises "Zweiter Weltkrieg", Nr. 3/4, 1975;

- Christiane Uhlig et al., "Tarnung, Transfer, Transit. Die Schweiz als Drehscheibe verdeckter deutscher Operationen [1938-1952]". publ. "Unabhängigen Expertenkommission Schweiz – Zweiter Weltkrieg", Zürich, 2001

US Military Intelligence Report EW-Pa 128

Enclosure No. 1 to dispatch No. 19,489 of Nov. 27, 1944, from the Embassy at London, England.

S E C R E T

SUPREME HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-27 November 1944

INTELLIGENCE REPORT NO. EW-Pa 128

SUBJECT: Plans of German industrialists to engage in underground activity after Germany’s defeat; flow of capital to neutral countries.

SOURCE: Agent of French Deuxieme Bureau, recommended by Commandant Zindel. This agent is regarded as reliable and has worked for the French on German problems since 1916.

He was in close contact with the Germans, particularly industrialists, during the occupation of France and he visited Germany as late as August, 1944.

1. A meeting of the principal German industrialists with interests in France was held on August 10, 1944, in the Hotel Rotes Haus in Strasbourg, France, and attended by the informant indicated above as the source. Among those present were the following: Dr. Scheid, who presided, holding the rank of S.S.Obergruppenführer and Director of the Heche [Hermandorff & Schönburg] Company

- Dr. Kaspar, representing Krupp Dr. Tolle, representing Rochling

- Dr. Sinderen, representing Messerschmitt Drs. Kopp, Vier and Beerwanger, representing Rheinmetall

- Captain Haberkorn and Dr. Ruhe, representing Bussing,

- Drs. Ellenmayer and Kardos, representing Volkswagenwerk

- Engineers Drose, Yanchew and Koppshem, representing various factories in Posen, Poland [Drose, Yanchewand Co., Brown-Boveri, Herkuleswerke, Buschwerke, and Stadtwerke] Captain Dornbusch, head of the Industrial Inspection Section at Posen Dr. Meyer, an official of the German Naval Ministry in Paris Dr. Strossner, of the Ministry of Armament, Paris.

2. Dr. Scheid stated that all industrial material in France was to be evacuated to Germany immediately. The battle of France was lost for Germany and now the defense of the Siegried Line was the main problem.

From now on also German industry must realize that the war cannot be won and that it must take steps in preparation for a post-war commercial campaign. Each industrialist must make contacts andalliances with foreign firms, but this must be done individuallyand without attracting any suspicion.

Moreover, the ground would have to be laid on the financial level for borrowing considerable sums from foreign countries after the war. As examples of the kind of penetration which had been most useful inthe past, Dr. Scheid cited the fact that patents for stainless steel belonged to the Chemical Foundation, Inc., New York, and the Krupp company of Germany jointly and that the U.S.Steel Corporation, Carnegie Illinois, American Steel and Wire, and national Tube, etc. were thereby under an obligation to work with the Krupp concern.

He also cited the Zeiss Company, the Leica Company and the Hamburg-American Line as firms which had been especially effective in protecting German interests abroad and gave their New York addresses to the industrialists at this meeting.

3. Following this meeting a smaller one was held presided over by Dr. Bosse of the German Armaments Ministry and attended only by representatives of Hech, Krupp and Rochling.

At this second meeting it was stated that the Nazi Party had informed the industrialists that the war was practically lost but that it would continue until a guarantee of the unity of Germany could be obtained. German industrialists must, it was said, through their exports increase the strength of Germany.

They must also prepare themselves to finance the Nazi Party which would be forced to go underground as Maquis (in Gebirgsverteidigung an Stellen gehen). From now on the government would allocate large sums to industrialists so that each could establish a secure post-war foundation in foreign countries. Existing financial reserves in foreign countries must be placed at the disposal of the Party so that a strong German Empire can be created after the defeat.

It is also immediately required that the large factories in Germany create small technical offices or research bureaus which would be absolutely independent and have no known connection with the factory. These bureaus will receive plans and drawings of new weapons as well as documents which they need to continue their research and which must not be allowed to fall into the hands of the enemy.

These offices are to be established in large cities where they can be most successfully hidden as well as in little villages near sources of hydro-electric power where they can pretend to be studying the development of water resources. The existence of these is to be known only by very few people in each industry and by chiefs of the Nazi Party. Each office will have a liaison agent with the Party. As soon as the Party becomes strong enough to re-establish its control over Germany the industrialists will be paid for their effort and cooperation by concessions and orders.

4. These meetings seem to indicate that the prohibition against the export of capital which was rigorously enforced until now has been completely withdrawn and replaced by anew Nazi policy whereby industrialists with government assistance will export as much of their capital as possible.

Previously exports of capital by German industrialists to neutral countries had to be accomplished rather surreptitiously and by means of special influence. Now the Nazi party stands behind the industrialists and urges them to save themselves by getting funds outside Germany and at the same time to advance the party’s plans for its post-war operation.This freedom given to the industrialists further cements their relations with the Party by giving them a measure of protection.

5. The German industrialists are not only buying agricultural property in Germany but are placing their funds abroad,particularly in neutral countries. Two main banks through which this export of capital operates are the Basler Handelsbank and the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt of Zürich. Also there are a number of agencies in Switzerland which for a 5 percent commission buy property in Switzerland, using a Swiss cloak.

6. After the defeat of Germany the Nazi Party recognizes that certain of its best known leaders will be condemned as war criminals. However, in cooperation with the industrialists it is arranging to place its less conspicuous but most important members in positions with various German factories as technical experts or members of its research and designing offices.

For the A.C. of S., G-2.WALTER K. SCHWINNG-2, Economic Section

Prepared by MELVIN M. FAGEN

Distribution:Same as EW-Pa 1,U.S. Political Adviser, SHAEF British Political Adviser, SHAEF

Fourth Reich plot revealed

Jewish group uncovers secret papers that prove conspiracy by 'ODESSA File' Nazis

Daniel Jeffreys | New York - Friday 6 September 1996 |

Secret United States documents uncovered by a Jewish human rights group have proved the existence of a Nazi support group that sought to smuggle people and gold out of Germany in 1945, and worked for the establishment of a Fourth Reich.

The group is vividly portrayed in Frederick Forsyth's novel "The ODESSA File". Mr Forsyth confirmed yesterday that his novel was based on reports of a meeting in France in August 1944.

This meeting is detailed in US documents seen by "The Independent" which were collected by a top-secret Intelligence operation called Project Safehaven at the end of the war.

"The ODESSA existed and they removed billions of dollars in looted Jewish assets from Germany," Elan Steinberg, executive director at the World Jewish Congress [WJC], said.

"Their plan was to re-establish the Nazi Party from safe havens outside Germany and many of the assets they smuggled out must still exist.".

The WJC is seeking to recover Jewish assets which were stolen by the Nazis.

The ODESSA document is a US Intelligence report stamped "Secret", written in November 1944. It is based on the work of a French Intelligence agent deployed by the Deuxieme Bureau which penetrated Nazi organisations in Paris during the occupation.

The agent observed an August 1944 meeting of German industrialists held in Strasbourg. It was presided over by SS Obergruppenführer Dr Scheid, managing director at the Heshe [Hermandorff & Schonburg] company before the war.

"Their plan was to smuggle gold, patents and art out of Germany along with top industrialists," Mr Steinberg said. "Meanwhile, the Nazi Party would re-establish itself in Germany as an underground movement".

The document was discovered in July when Mr Steinberg gained access to recently declassified papers from the National Archive in Washington.

Mr Steinberg has authenticated the report and linked it to others which show that the German Reichsbank was involved in the plot.

According to a secret US State Department telegram dated 4 December 1945, the Reichsbank maintained a depot of gold at the Swiss National Bank throughout the war. By 1945 it had accumulated bullion worth $123m which was earmarked for ODESSA operations.

The Strasbourg meeting laid out a comprehensive plan for resurrecting the Reich. Executives from Volkswagen, Krupp Steel, Brown-Boveri, Messerschmidt, Zeiss and Leica were ordered to establish operations overseas and finance the Nazi Party from abroad.

The Intelligence report quotes SS Obergruppenführer Scheid on post-war strategy:

"From now on, German industry must realise that the war cannot be won and that it must make steps in preparation for a post-war commercial campaign," he said.

This and other documents in the possession of the WJC may have adverse implications for the modern descendants of leading German corporations.

"We now have sufficient evidence for an indictment," Elan Steinberg said yesterday.

The ODESSA document came to light after the WJC failed to persuade Switzerland to open secret Nazi bank accounts in May this year.

"The documents are evidence of the biggest robbery in the history of mankind," said Mr Steinberg, who has now forced the Swiss government to begin a full inquiry.

'The Independent' reported yesterday that Hitler had been reported to have held numbered accounts at Union Bank of Switzerland.

"UBS yesterday issued a statement denying that it was still handling funds deposited by Nazis during the war".

Robert Vogler, the bank's chief spokesman in Zürich, could not say whether such an account had ever existed but he said that all funds belonging to Germans were frozen after the war, their owners vetted, and those traced to known Nazis handed over to the Allies.

"Few people believed Frederick Forsyth when he said the villain of "'The ODESSA File", Eduard Roschmann, the Butcher of Riga, was a real character", writes Steve Boggan.

"Or that a meeting of high-ranking SS officers and industrialists took place at the Maison Rouge hotel in Strasbourg in 1944 to discuss ways of moving Nazi gold out of Germany and France".

Eduard Roschmann was an Austrian Nazi SS-Obersturmführer and commandant of the Riga ghetto during 1943.

As a result of a fictionalised portrayal in the novel "The Odessa File" by Frederick Forsyth and its subsequent film adaptation, Roschmann came to be known as the "Butcher of Riga".

Gertrude Schneider, a historian and a survivor of the Riga ghetto, sharply disputes this fictionalised image of Roschmann.

She describes this fiction novel as "lurid" and containing "many inaccuracies"

Among the inaccuracies of Forsyth's fictional version of Roschmann are:

- Roschmann never murdered a Wehrmacht captain at the Latvian port of Liepāja to force his way onto an evacuation ship.

- No mention is made of Rudolf Lange, whom Schneider describes as the real Butcher of Riga.

- Kurt Krause is portrayed as Roschmann's deputy, rather than as his predecessor

- Alois Hudal is incorrectly identified as the "German apostolic nuncio" and a cardinal.

- Roschmann is described as having been sheltered in a "big" Franciscan house in Genoa which apparently never existed.

- ODESSA is portrayed as having purchased 7,000 Argentinian passports for people like Roschmann. No explanation is given for why, if this were so, Roschmann would need a travel document from the International Red Cross.

- The head of ODESSA is identified as former SS General Richard Glücks, who in fact committed suicide in 1945.

Yet Mr Forsyth always insisted that large elements of his book were true, based on information from "friends in low places". The US report talks of a meeting at the Hotel Rotes Haus. "I believe there were a number of meetings there at which the SS and industrialists carved up much of the proceeds of the Third Reich", he said.

The basis for this plan had been developed years earlier, as on 11 September 1940 Reich Propaganda Minister Josef Göbbels delivered a speech, 'The Europe of the Future' to Czech intellectual workers and journalists stating: “I am convinced that in 50 years, people will no longer think in terms of countries….

"In those days people will think in terms of continents…. No single European nation can in the long run be allowed to standin the way of the general process of organization.”

In the same year [1940] as Göbbels’ speech, Nazi Minister of Economic Affairs [1937-1945] Walther Funk wrote a 16-page booklet, "The Economic Future of Europe", and called for a 'Central European Union' and 'European Economic Area'. In 1942, Funk co-authored "The European Economic Community", in which he declared, “There must be a readiness to subordinate one’s own interests in certain cases to those of [the EC]".

Funk’s co-authors echoed his sentiments. Nazi academic Heinrich Hunke wrote:

"Classic national economy..is dead…community of fate which is the European economy…fate and extent of European co-operation depends on a new unity economic plan".

Fellow Nazi Gustav König observed:

"“We have a real European Community task before us…I am convinced that this Community effort will last beyond the end of the war".

According to journalist Curt Riess in "The Nazis Go Underground" [1944], it was on the morning of 9 November 1942 that Hitler’s Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler in his private office in the Brown House in Munich confided to Martin Bormann that while Germany may have to capitulate militarily, "never must the National Socialist German Workers Party [Nazi Party] capitulate. That is what we have to work for from now".

Relevant to this effort, Himmler organized everything right down to the last detail regarding Nazis going underground and spreading throughout the world to fulfill their plan, perhaps in two generations.

Preliminary work and planning was done by Himmler at the Gestapo building in the Prince Albrechtstrasse, Berlin, and the major Nazi undergound movement began 16 May 1943 at 11 Königsallee in Berlin under SS Generals Werner Heissmeyer and Ernst Kaltenbrunner. Curt Riessalso revealed that "[The Nazi Underground] organization in Argentina is all set up and waiting impatiently for the ‘go-ahead’ signal".

The documents, Accession Number 56-75-101, Agency Container Number 169, File Number BIS/2/00, concern Germany's "looted" gold being transferred to the 'Bank for International Settlements' in Switzerland.

One important paragraph [#9] says:

"It is clear both from correspondence and from testimony that the management of the B.I.S. during the war was 'in the hands of the Administration Council, in which the AXIS representatives have an authoritative influence' and that in 1942 the Germans favored the reelection of President McKittrick whose 'personal opinions' they characterized as 'safely known'".

[It has been claimed by some researchers that the 7 most powerful Bankers in the world -who collectively control over 80 percent of all global financial transactions and over 60 percent of all global trade- have in the past met regularly at the Bank of International Settlements or 'B.I.S.' office in the fitly named 'Tower of Basel' in Basel, Switzerland].

Enclosed in the file is a clipping from the "New York Times", date not included but appears to be in 1945, that states:

"McKITTRICK SLATED FOR POST AT CHASE.

He Will Take Over Duties as Vice President of Bank Here Next Autumn.

Thomas H. McKittrick, American banker who has served as president of the Bank for International Settlements [B.I.S.] since the beginning of 1940, will become a vice president of the [Rockefeller's] Chase National Bank of New York next fall, Winthrop W. Aldrich, chairman of the board of Chase, announced yesterday".

The article ends by quoting McKittrick:

"I realize it is my duty to perform a neutral task in wartime. It is an extremely difficult and trying thing to do, but I'll do the best I can".

Another formerly Top Secret document declassified was "Subject: Conversation in Switzerland with Mr. McKittrick, President of the Bank for International Settlements" from Orvis A. Schmidt to Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau, dated 23 March 1945. It describes McKittrick's dealings with the real head of the Nazi banking system, a Vice President named Puhl.

"Puhl was described by McKittrick as a career banker who had been with the Reichsbank for some twenty years, who does not share the Nazi point of view... the Swiss National Bank said that in order to be sure they were not obtaining looted gold they had requested a member of the Reichsbank, whom they regarded to be trustworthy, to certify that each parcel of gold which they purchased had not been looted. The person who had done this certifying was Puhl".

Puhl was Reichsbank Senior Vice President Emil Johann Rudolf Puhl.

He was in charge of taking booty into the bank and was in charge of it for the Nazis. His Senior Shipping Clerk Albert Thoms said that they needed up to thirty men to help him sort and repack the valuables, which consisted of "millions in gold Marks, pounds sterling, dollars and Swiss francs, 3,500 ounces of platinum, over 550,000 ounces of gold, and 4,638 carats in diamonds and other precious stones, as well as hundreds of pieces of works of art" ["Aftermath," Ladislas Farago, Avon, 1974].

This material was shipped out of the country in Operation Fireland or Aktion Feuerland in German. "The transaction was named 'Land of Fire' after the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego at the southern extremity of Argentina and Chile, the area to which some of of the shipments were originally consigned".

Hitler, exhausted, drained of the charisma of the glory days of the thirties and the conquest years of the early forties, was going through the gestures of military leadership mechanically as his troops fell back on all fronts. Martin Bormann, forty-one at the fall of Berlin, and strong as a bull, was at all times at Hitler’s side, impassive and cool.

His be-all and end-all was to guide Hitler, and now to make the decisions that would lead to the eventual rebirth of his country. Hitler, his intuitions at peak level despite his crumbling physical and mental health in the last year of the Third Reich, realized this and approved of it.

In the Spring of 1944, Merck and Company, Inc. received a large cash infusion from Martin Bormann.

This at the time Merck's president, George W. Merck, was advising President Roosevelt, and initiating strategies, as America's biological weapons industry director. According to CBS News correspondent Paul Manning, the lion's share of the Nazi gold went to 750 corporations, largely including Merck, to secure a virtual monopoly over the world's chemical and pharmaceutical industries. This was done not only for Germany's economic recovery, but to assure the rise of 'The Fourth Reich'.

Merck then, along with Rockefeller partner I.G. Farben, received huge sums of money from the Nazi war chest to actualize Hitler's proclaimed 'vision of a thousand-year Third Reich [and] world empire.

This was outlined with clarity in a document called 'Neuordnung,' or 'New Order,' that was accompanied by a letter of transmittal to the [Bormann led] Ministry of Economics.

"Bury your treasure,' Hitler advised Bormann, 'for you will need it to begin a Fourth Reich".

Bormann apparently ignored his Führer, and in a momentary burst of Christianity, heeded Christ by not burying his treasure, but investing and increasing it, setting in motion the 'flight capital' scheme on 10 August, 1944, in Strasbourg. The treasure, the golden ring, he envisioned for the new Germany was the sophisticated distribution of national and corporate assets to safe havens throughout the neutral nations of the rest of the world.

The myth of "ODESSA" was overlaid with the idea of a secret conference of Nazi government and economic leaders, who had supposedly met in the Hotel Maison Rouge in Strasbourg on 10 August 1944, and who had provided the necessary funding for the organization's endeavors.

Along with other leading figures within the Third Reich, General Nazi Party Secretary Martin Bormann had apparently come to the conclusion by the summer of 1944 that the war was invariably lost. The only hope for the future survival of himself and other head Nazis, all of whom faced execution if captured, lay in utilizing their own resources for their escape from Europe. He deemed it absolutely necessary to bring the enormous Nazi treasure out of Europe and to invest it securely.

Entire industries must be transferred out of Germany. Key Nazi firms must establish roots abroad in order to avoid rapacious reparation payments. Thousands of war criminals, most of whom were members of the SS, needed assistance to leave the Reich and secure hiding in the prepared settlements and German colonies of foreign lands. In order to secure and coordinate the financial backing for such operations, Bormann apparently called a hidden meeting of business leaders and top-ranking members of the war and naval ministries to Strasbourg in the summer of 1944, without the knowledge of Heinrich Himmler or Adolf Hitler.

The results of this meeting were indeed supposedly quite substantial, for enormous money amounts, hidden currencies, and gold reserves were eventually moved out of Germany. Besides establishing the firm foundations for the economic security and growth of Nazi firms abroad, the money apparently served to finance the actual escape of such individuals through secret organizations like Odessa as well.

Heinz Schneppen ["ODESSA und das Vierte Reich: Mythen der Zeitgeschichte". Berlin: Metropol Verlag, 2007] argues, however, that any critical historical analysis of the meeting in Strasbourg proves that the event was sheer fantasy. Many of its alleged participants were senile, already dead, or in concentration camps. Indeed, their presence, as well as the participation of representatives from government ministries, simply cannot be proven.

In addition, the alleged civilian chairman of the meeting, a Dr. Scheid, was indeed a ceramic industrialist and leading official in Albert Speer's ministry, but he would have been a poor choice of an individual who could have brought the SS into the plan. Having experienced immense difficulty himself in obtaining membership in the Nazi Party, he never even became a member of the SS.

Not only are the reports about the participants not convincing, but justifiable doubt exists concerning the meeting place as well. Schneppen places into serious question whether a conspiratorial meeting could have actually taken place only weeks following the attempt on Hitler's life [20 July 1944], when the party was hunting mercilessly for any hint of defeatism. In addition, skepticism concerning the funds to which the conference participants had access is necessary.

Throughout the fall of 1944, the Reich was in possession of only scant amounts of gold and foreign currencies in order to finance the war. The idea of any substantial capital transfer out of Germany seems highly improbable, especially in light of the increasingly restrictive rules concerning financial transactions with Nazi Germany that the Allies were imposing at the time upon neutral states, like Switzerland.

In the end, any efforts on the part of Odessa, or any plans finalized at the Strasbourg Conference to procure financing for the organization, could only succeed if a foreign power overseas actually allowed a "Fourth Reich" to take root.

Jeffrey Bale, a Columbia University expert on clandestine Nazi networks, said historians have debated whether such a meeting could have taken place because it came a month after the attempt on Adolf Hitler's life, which had led to a crackdown on discussions of a possible German military defeat. Bale said the Red House meeting was mentioned in Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal's 1967 book "The Murderers Among Us" and again in a 1978 book by French Communist Victor Alexandrov, "The SS Mafia".

The secret Nazi plan was also described in American official Sumner Welles’ "The Time for Decision" [1944].

Adolf Hitler in the second part of his final 'Political Testament' given in Berlin on 29 April 1945 at 4 AM requested that Nazi Party head Martin Bormann and others continue the work of the Nazis after Hitler’s death. He remarked, “Let them be conscious of the fact that our task, that of continuing the building of a National Socialist State, represents the work of the coming centuries, which places every single person under an obligation always to serve the common interest and to subordinate his own advantage to this end”.

In the first part of his final 'Political Testament'. Hitler had forecast, “From the sacrifice of our soldiers and from my own unity with them unto death, will in any case spring up in the history of Germany, the seed of a radiant renaissance of the National-Socialist [Nazi] movement and thus of the realization of a true community of nations".

An important report was given by Herbert W. Armstrong from the United Nations building on 9 May 1945, just nine months after the secret meeting between German industrialists. I

n that report he said:

"The war is over, in Europe—or is it?.....We don’t understand German thoroughness.....From the very start of World War II, they have considered the possibility of losing this second round, as they did the first—and they have carefully, methodically planned, in such eventuality, the third round—World War III Hitler has lost. This round of war in Europe is over. And the Nazis have now gone underground".

David Lee Preston wrote in 'Hitler’s Swiss Connection' ["The Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine", 5 January 1997] former Nazi Reichsminister of Finance Hjalmar Schacht "was quoted as saying National Socialism would conquer the world without having to wage another war".

Heinz Schneppen. "ODESSA und das Vierte Reich: Mythen der Zeitgeschichte" Berlin: Metropol Verlag, 2007.

Reviewed by Alexander Peter d'Erizans [CUNY Manhattan]

Published on H-German [August, 2011]

Commissioned by Benita Blessing

A Scrutiny of the ODESSA Myth

The legend of ODESSA, a secretive SS [Schutzstaffel] organization formed in the aftermath of the Second World War in order to smuggle Nazi officials and treasure out of Germany with the intention of striking roots for the establishment of a "Fourth Reich," has captivated novelists, the media, political groups, government security services, and dominant global personalities throughout the last half-century. [1]

In his work, "ODESSA und das Vierte Reich: Mythen der Zeitgeschichte", the former West German diplomat Heinz Schneppen seeks to separate myth from reality. While he vehemently challenges the notion that ODESSA actually existed, Schneppen wishes primarily to elucidate the particular factors accounting for why such a legend actually arose in the first place.

In so doing, he hopes to offer insight into the genesis of myth-making itself and the formulation of conspiracy theories throughout history. For Schneppen, the idea of ODESSA has been particularly durable for a variety of reasons.

Certainly, ignorance has played a significant role in the myth's persistence. Many of those individuals who have promoted the existence of ODESSA, such as Simon Wiesenthal, have demonstrated insufficient knowledge concerning the sources and inadequate training required for critical analysis of the latter. Political motives, ideological bias, and outright disinformation have often accompanied this shortage of professionalism as well, resulting in vague hypotheses supported by unverifiable data masquerading as facts.

Professional shortcomings or political biases of myth-makers, however, only go so far in explaining the production and staying power of the idea of ODESSA, for Schneppen argues that such stories ultimately satisfy a collective need as well, particularly during periods of rapid rupture and flux like the complete collapse of Nazi Germany.

On the one hand, for many of the Third Reich's most diehard supporters, the end of the Second World War produced a profound spiritual vacuum. Although their world lay in rubble, devoted Nazis still had to believe that the timeless, indestructible Germany of their most recent and glorious past had survived. To them, therefore, lay the task of sustaining the idea and substance of the Nazi regime in the postwar period. As the racial elite of the Nazi Volksgemeinschaft [national community], to whom it owed unwavering allegiance, the SS invariably assumed the leading role in achieving this objective.

After 1945, with the Reich in ruins, the loyalty of the SS shifted from Adolf Hitler to a spiritual Germany of eternal "blood and soil". Since the organization's members could not realize their dreams in Germany itself, perhaps they could construct a new empire in some foreign land, a project that would require the services of a secretive human-smuggling outfit like ODESSA in order to actually transport them and other leading Nazis to their new home.

The sentiments that gave care and comfort to Nazi supporters, however, at the same time dramatically heightened the concerns and fears of those individuals, particularly members of ethnic and political groups the Nazis had targeted, who were afraid [to the point of paranoia] of any indication that National Socialism would experience a revival, indeed, that it had never truly been extinguished. Ultimately, then, Schneppen argues that contrary expectations served to ensure that the myth of ODESSA would receive sustained nourishment throughout the years following 1945.

In the end, Schneppen admits that the factors giving birth to such legends as ODESSA must move beyond the authors themselves as well as the particular historical contexts within which they are living. As old as man himself, such conspiracy theories simply seem too irresistible for some to concoct and never abandon, for they rest upon the exciting, intriguing, and often dramatic premise that behind the appearance of reality, powers are constantly at work formulating plans [almost always devious] revealed to no one.

Such myths extend beyond the empiricism of causes and contexts which historians seek to discern and for which they seek to account. Nonetheless, with all their irrationality, such myths often demonstrate plausibility by referring to particular facts and events, whose truth the most ardent skeptics could not even deny. In addition, the very strength of conspiracy myths is their ever elusive nature, for that which does not exist also cannot be entirely refuted.

Schneppen wrestles with the imaginings that ultimately forged the myth of a secret Nazi organization that ferried top-ranking members of the Third Reich out of Europe by zeroing in on the three principal pillars supporting the legend:

The alleged formation of ODESSA itself, the Strasbourg Conference of August 1944, and the "Argentinean Connection" linking Nazis with the government of Juan Perón.

ODESSA was the means; Strasbourg the decisive site, where leading Nazis apparently co-ordinated plans to secure their own future amidst a rapidly deteriorating military situation; and Argentina was the goal.

The author first discusses the theory of the ODESSA organization and its shortcomings. Supposedly, in the vicinity of Odessa in 1947, a worldwide secretive escape outfit of leading SS and Gestapo members formed, taking the name of the city in which it was founded. The group provided a thickly connected, smoothly functioning network in which all Nazi escapees could rely on a contact point every forty kilometers.

Over the so-called cloister route, ODESSA apparently smuggled fleeing Nazis first to Genoa and Rome with the assistance of the Vatican and Italian authorities, and from there to Perón's Argentina, which served as a final "end station". The organization, however, supposedly occupied itself with more than just ferrying Nazi criminals out of Europe.

Odessa energetically sought to undermine the Federal Republic from within by infiltrating its parties and government apparatus at the national, regional, and local levels.

It strived to gain a foothold in the economy, the judicial system, and the police as well. Its members sought to drag out the investigation and pursuit of Nazi criminals, and if a particular case reached court, ODESSA ensured that each defendant had access to the best defense money could buy.

Throughout the post-war period, the organization apparently became a fervent organizer of neo-Nazi activities as well. Odessa supposedly even officially declared war on Israel, continuously seeking to thwart the operations of the country's commando units, and assassinate its secret agents.

A series of ODESSA cells apparently operated throughout such cities as Rosenheim, Stuttgart, Kempten Mannheim, Berchtesgaden, Dachau, all co-ordinated on the ground by SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny.

Guy Walters, in his 2009 book "Hunting Evil", stated he was unable to find any evidence of the existence of the ODESSA network as such, although numerous other organisations such as Konsul, Scharnhorst, Sechsgestirn, Leibwache, and Lustige Brüder have been named including Die Spinne [The Spider] run in part by Hitler's commando chief Otto Skorzeny.

Periodically, small groups of members secretly met in hotels and cafes in order to hatch plans and to co-ordinate operations.

In order to fund such activities, Odessa supposedly harnessed the profits that its members had made during the war, particularly during the implementation of the Final Solution.

Secured in the banks of neutral lands, such as Switzerland, the funds were readily available. In addition, throughout the Arab world, Odessa traded stolen weapons and munitions for marijuana and opium. Working in conjunction with various Mafia networks, the organization then would sell the drugs on the global market.

Despite the often detailed and comprehensive depiction of ODESSA, Schneppen indicates that all serious historical inquiry speaks against the existence of any such organization. Scholars and watchdog groups of neo-Nazi activities refute its existence due to the lack of evidence.

Ultimately, however, the author argues that simple logic speaks against the existence of ODESSA as well. First, considering that numerous government and non-government bodies within not only Germany, but the free states of the rest of the world, maintain a close watch on the slightest stirrings of fascism, the idea that a secret, widespread, and active Nazi global network could actually conduct its work is simply inconceivable.

In addition, since the cause ODESSA reportedly pursued had only the slightest chance of success, one must consider the former Nazi functionaries in the organization as either complete phantoms or total idiots, and nothing in-between. After all, as Schneppen argues, only the prospect of gaining power could ultimately enable a politically minded individual to persist decades-long in order to achieve a particular goal.

Even though conspiracy theorists lend much weight to the biographies of certain prominent Nazis who fled, such as Adolf Eichmann [SS Obersturmführer, head of Jewish affairs at the Reich Main Security Office], Josef Mengele [camp doctor at Auschwitz], Franz Stangl [commandant of Treblinka], Eduard Roschmann [commandant of Riga Ghetto], and Josef Schwammberger [SS-Oberscharführer and former ghetto commandant in Przemysl], the author states that none of the above individuals ever referred to assistance that ODESSA apparently provided to them.

Historian Gitta Sereny wrote in her 1974 book "Into that Darkness", based on interviews with the former commandant of the Treblinka extermination camp, Franz Stangl, that an organisation called ODESSA had never existed although there were Nazi aid organisations

Nazi concentration camp supervisors denied the existence of an organisation called ODESSA.

In his interviews with Sereny, Stangl denied any knowledge of a group called the ODESSA.

Recent biographies of Adolf Eichmann, who also escaped to South America, and Heinrich Himmler, the alleged founder of the ODESSA, made no reference to such an organisation.

Certainly the escape stories of such prominent Nazis reveal certain similarities.

An exchange of identities was vitally important for all of them, which could and did take place at various points: before the collapse of the Third Reich, within internment camps, after release from prison, or during escape. In addition, certain commercial human-smuggling organizations, the Red Cross, and the Catholic Church did assist escapees for a variety of material and humanitarian concerns, sometimes co-operating with each other in their endeavors.

Nonetheless, their efforts in helping the escapees, even if at times co-ordinated, did not necessarily represent a systematic plan of any secret, overarching SS organization called ODESSA. The myth of ODESSA was overlaid with the idea of a secret conference of Nazi government and economic leaders, who had supposedly met in the Hotel Maison Rouge in Strasbourg on 10 August 1944, and who had provided the necessary funding for the organization's endeavors. As for ODESSA, Schneppen details the theory, while pointing out its limitations.

Along with other leading figures within the Third Reich, General Nazi Party Secretary Martin Bormann had apparently come to the conclusion by the summer of 1944 that the war was invariably lost. The only hope for the future survival of himself and other head Nazis, all of whom faced execution if captured, lay in utilizing their own resources for their escape from Europe. He deemed it absolutely necessary to bring the enormous Nazi treasure out of Europe and to invest it securely. Entire industries must be transferred out of Germany. Key Nazi firms must establish roots abroad in order to avoid rapacious reparation payments.

Thousands of war criminals, most of whom were members of the SS, needed assistance to leave the Reich and secure hiding in the prepared settlements and German colonies of foreign lands. In order to secure and coordinate the financial backing for such operations, Bormann apparently called a hidden meeting of business leaders and top-ranking members of the war and naval ministries to Strasbourg in the summer of 1944, without the knowledge of Heinrich Himmler or Adolf Hitler.

The results of this meeting were indeed supposedly quite substantial, for enormous money amounts, hidden currencies, and gold reserves were eventually moved out of Germany. Besides establishing the firm foundations for the economic security and growth of Nazi firms abroad, the money apparently served to finance the actual escape of such individuals through secret organizations like ODESSA as well.

The author argues, however, that any critical historical analysis of the meeting in Strasbourg proves that the event was sheer fantasy. Many of its alleged participants were senile, already dead, or in concentration camps. Indeed, their presence, as well as the participation of representatives from government ministries, simply cannot be proven. In addition, the alleged civilian chairman of the meeting, a Dr. Scheid, was indeed a ceramic industrialist and leading official in Albert Speer's ministry, but he would have been a poor choice of an individual who could have brought the SS into the plan. Having experienced immense difficulty himself in obtaining membership in the Nazi Party, he never even became a member of the SS.

Not only are the reports about the participants not convincing, but justifiable doubt exists concerning the meeting place as well. Schneppen places into serious question whether a conspiratorial meeting could have actually taken place only weeks following the attempt on Hitler's life [20 July 1944], when the party was hunting mercilessly for any hint of defeatism. In addition, skepticism concerning the funds to which the conference participants had access is necessary.

Throughout the fall of 1944, the Reich was in possession of only scant amounts of gold and foreign currencies in order to finance the war. The idea of any substantial capital transfer out of Germany seems highly improbable, especially in light of the increasingly restrictive rules concerning financial transactions with Nazi Germany that the Allies were imposing at the time upon neutral states, like Switzerland.

In the end, any efforts on the part of ODESSA, or any plans finalized at the Strasbourg Conference to procure financing for the organization, could only succeed if a foreign power overseas actually allowed a "Fourth Reich" to take root. To this topic the author proceeds to turn through a discussion of how Perón's Argentina served as the destination point for Nazi men, money, and gold.

Yet again, however, the author points out that the evidence is lacking, not only concerning the transfer of funds, but for conceptualizing Argentina as the staging area for future Nazi plans as well. For Schneppen, a transfer of capital to Argentina could simply not have taken place. In January 1944, Argentina had broken diplomatic relations with the Reich, and on 27 March 1945, had actually declared war on Germany.

Prior to these events, however, largely because of pressure from the United States, Argentina had already restricted trade relations as well as bank and financial transactions with Nazi Germany. The rupture of diplomatic relations severed vital contacts between German firms and their Argentinean subsidiaries, although Allied blockade efforts had in reality stifled such relations much earlier. A few days after the declaration of war, all branch offices of German firms as well as the fortunes of German nationals resident in Argentina came under state control, and when the war ended, the liquidation of such industries took place. Under such circumstances, Argentina hardly seems like an ideal site for the transfer and hiding of Nazi fortunes.

Upon assuming power in the summer of 1946, as Schneppen points out, Perón accelerated the above efforts. From time to time, German firms certainly sought, with varying degrees of success, to delay, or even evade, the measures of the Argentinean authorities. Before the official break of diplomatic relations, for example, certain German businesses aimed to secure their wealth by investing in bogus firms.

The particular economic concerns of the industries involved, however, rather than any grand political and ideological design in coordination with ODESSA, accounted for such behavior. In addition, these admittedly secretive moves of German firms to ensure their own survival never seemed to take place with the close cooperation of Perón, who, despite genuine German sympathies extending throughout his military career and awe at the manner in which the Nazis and Fascists had mobilized their populaces, first and foremost sought to promote the material interests of Argentina through the nationalization and the sale of Reich business enterprises.

Perón certainly demonstrated an eagerness to acquire Germany's "human capital" throughout the postwar period. Again, however, his policy was primarily nationalist, and not part of a wider scheme to facilitate the construction of a "Fourth Reich" within his country.

When he took power, Argentina was one of the wealthiest nations on the globe as a result of its extensive exports of agricultural products to the Allies during the Second World War. In order to maintain prosperity in a postwar world,

Perón believed that his country needed to establish a more diversified economy through industrialization. Such economic changes necessitated skilled workers that the country simply did not have, but which could be acquired through the immigration of Europeans, most notably Germans [approximately 22,400 arrived in Argentina between 1945 and 1949] seeking to start a new life outside of Europe. For the most part, then, according to the author, Perón ran his government primarily as a pragmatist and opportunist, not an ideologue.

To drive the point home that Argentina did not become a bastion of Nazism, the author points out that the many German technicians, engineers, and natural scientists who immigrated to the country had few political motives.

For Schneppen, one must distinguish not only between Nazis and the majority of nonpolitical immigrants, but also between Nazis and the very small number of war criminals, as defined by the Allied Control Council Law No. 10 of December, 1945, who sought refuge in Argentina. Those individuals who actually had held high posts in the Nazi ruling structure and faced criminal charges in Germany comprised an extremely small percentage of immigrants, only about 2 or 3 percent.